African American History

African American History

August 7, 2014

Smithsonian Recognizes African American Legacy in Oak Bluffs

In the years when much of America was racially segregated, Oak Bluffs was a place of refuge for African Americans. The town will be included an in upcoming permanent Smithsonian exhibit in Washington, D.C. An event will be held Thursday at the Union Chapel.

July 31, 2014

For Friendship and to Pay It Forward

On Wednesday, elder members and former presidents of the Cottagers gathered around tables and took turns sharing memories.

August 19, 2013

Looking at History and In the Mirror Are Keys to Addressing Pillars of Racism

Politics are poisoned by bitter partisanship, economic disparities between whites and minorities are widening and trust between these groups seems to be eroding, complicating efforts to bridge America’s divisions. These were among the many observations by panelists at the annual Hutchins Forum Thursday evening in Edgartown.

July 18, 2013

Boxing Her Way to Equality and Justice

The African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard began as part of a promise to a little boy, and in 1998 the Shearer Cottage was dedicated as the first site on the Trail. The ambition was to reach a total of eight sites. That there were many stories was obvious, but the depth and range of the experiences that make up the tapestry of the African American experience on Martha’s Vineyard was amazing. From fugitive preachers to nationally known politicians, all the struggles and triumphs of people of color were part of the story of this Island.

February 28, 2013

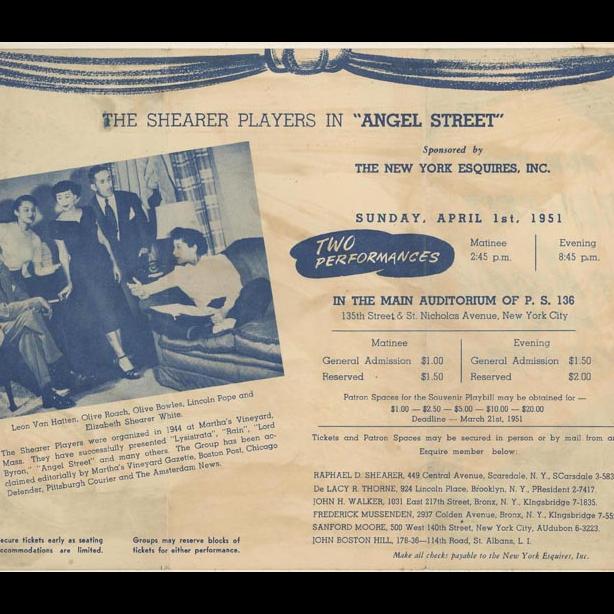

Black Summer Theatre's History Retold

Editor’s Note: Olive Tomlinson spoke with Linsey Lee, oral history curator for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, about her recollections of Liz White’s Shearer Summer Theatre, one of the first summer theatre groups on the Island after World War II. An actress who felt stymied by the stereotyped African American roles available to her on Broadway, in the summers Liz returned to Oak Bluffs where her family owned and operated Shearer Cottage, a popular inn for vacationing African Americans.

September 28, 2012

Long Legacy of Open Doors Shearer Cottage Turns 100

The day before the centennial celebration of Shearer Cottage in Oak Bluffs, Gretchen Tucker Underwood noticed that the landscaping around the 100-year-old red inn on Rose avenue was not quite ready for the impending party.

August 20, 2012

W.E.B. Du Bois Panel Tackles Hard Questions of Poverty

There were plenty of problems on the table and few easy solutions at hand as an influential panel convened Thursday evening to discuss the issue that has gone unnoticed in this issue-laden presidential election year: unemployment and high poverty rates in the African American community.

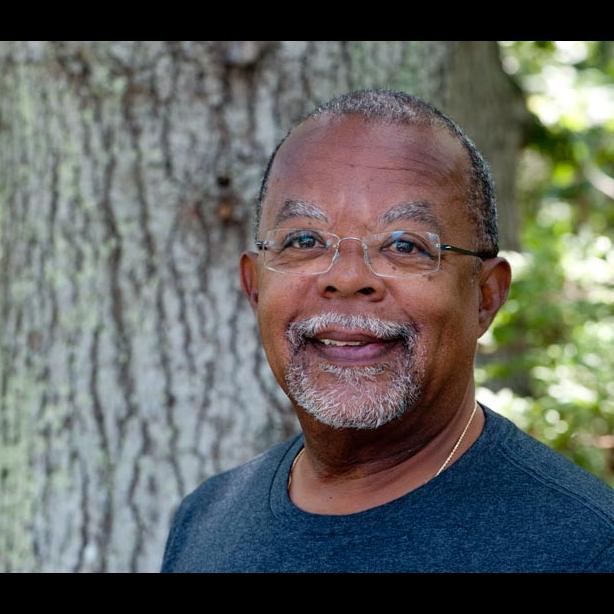

When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, few “would have anticipated that in the year 2012, we would have the largest black middle class in American history,” said forum host Dr. Henry Louis (Skip) Gates Jr.

August 16, 2012

Hosting Forums, Finding Roots And Three-Wheeling with a Friend

Henry Louis (Skip) Gates Jr. is passionate about roots. The Harvard professor, writer and genealogist first started on a family tree as a nine-year-old, after his grandfather’s burial, wanting to know about his connection to his father and grandfather. He’s followed his passion in his professional life, through scholarship and his popular television shows tracing people’s genealogy, and in the personal realm: still working on the family tree, he is trying to find the identity of his great-great-grandfather.

July 12, 2012

Cottagers Tour Strides Through Island’s African American History

The Highlands, as they are familiarly known, are located on East Chop, the general boundary being laid out like the Methodist Camp Ground in Oak Bluffs, with a central circle ringed by house lots along curving avenues.

July 5, 2012

African Americans on Martha’s Vineyard, Then and Now

On a recent sparkling morning at Inkwell Beach, summer resident and retired Boston judge Ed Redd emerged from his daily swim and carefully considered a question: Does Martha’s Vineyard still retain a certain magic for African Americans — longtime residents and new visitors alike? Judge Redd, a barrel-chested, affable ambassador for the Polar Bears, the historic group that finds invigoration and spirituality in morning swims at the Inkwell from July 4 to Labor Day, didn’t pause for long.