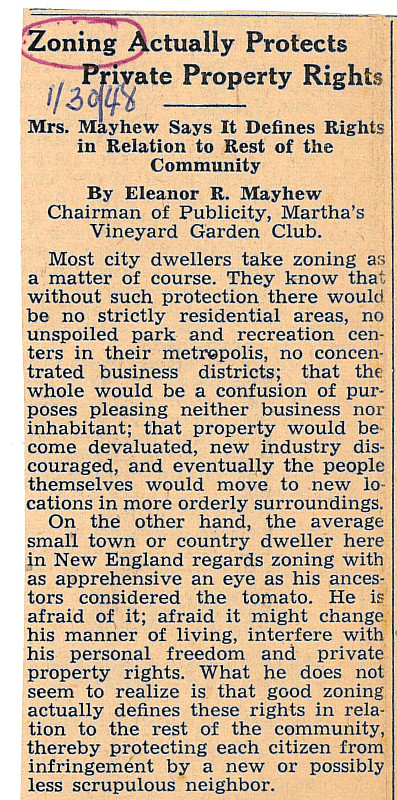

Most city dwellers take zoning as a matter of course. They know that without such protection there would be no strictly residential areas, no unspoiled park and recreation centers in their metropolis, no concentrated business districts; that the whole would be a confusion of purposes pleasing neither business nor inhabitant; that property would become devaluated, new industry discouraged, and eventually the people themselves would move to new locations in more orderly surroundings.

On the other hand, the average small town or country dweller here in New England regards zoning with as apprehensive an eye as his ancestors considered the tomato. He is afraid of it; afraid it might change his manner of living, interfere with his personal freedom and private property rights. What he does not seem to realize is that good zoning actually defines these rights in relation to the rest of the community, thereby protecting each citizen from infringement by a new or possibly less scrupulous neighbor.

Only Wishful Thinking

In long established small towns such as those on the Vineyard, there is a tendency to believe - it might also be called wishful thinking - that because there never has been, there never will be such unsightly things as ribbon slum development along the highways, commercial expansion beyond Main street, or indeed any one of the haphazard eyesores that have despoiled the villages and countryside in places as close to us as Cape Cod. This kind of thinking is dangerous. It does not admit of progress; it does not prepare for the future; it does not recognize change.

The New Englander dislikes change almost more than he dislikes regulation. Therefore the fact that each community must make its own zoning laws, that they can thus be so devised as to protect that community from any great degree of change, should appeal to him. There need be no more restriction than he and his neighbors decide are essential to that protection, for they are the ones who write the ordinance; it is not a decree superimposed by officialdom in Washington or Boston. And once a zoning ordinance is accepted by a town, it can be amended or expanded to meet new problems and conditions as they arise through the same democratic processes of open hearings and town meeting.

Zoning has been defined as a collective self control, by means of which a community may control its own life and growth for the best good of its citizens. As applied to the Vineyard, it seems the best, the safest and simplest way to assure that future property owners, possibly less interested than those long domiciled here, in retaining the essential rural and recreational character of the Vineyard than in turning a penny, abide by restrictions which up to the present have been imposed by public opinion and pride of native heath!

There Are No Set Rules

There are no set rules for zoning, the basic purpose, however, being to divide the town or township into commercial, residential or purely rural districts. This may be expanded to include regulation of outdoor advertising and protection of highway frontages from business development. In the case of larger towns, zoning serves to centralize the business or industrial area, keeps it from expanding into residential streets, thereby lowering their desirability and value as such, and from stretching out on to the approaches to town and defacing them.

In the villages, it protects the rural character of the community, keeps business - the general store, gas station, postoffice etc. - within logical limits, prevents the opening up of hitherto recreational or scenic areas to the encroachment of such undesirable structures as lunch carts, one-cylinder service stations, overnight cabins, billboards and the like. It does not, however, attempt to control farm or home use of rural properties.

The State Planning Board of Pennsylvania has compiled a zoning primer which states clearly and succinctly the principles and objectives of zoning from which the following, as most applicable to the Vineyard, are taken.

Zoning must be reasonable. It should be no more restrictive than is necessary to accomplish its objectives.

Zoning must be based on complete information, i. e. intimate knowledge of conditions and trends, things as they are and as they are likely to be.

Zoning must be individual. Every zoning ordinance is as much a special problem as every prescription written by a good doctor. Every town, however, small, has its own character and preferences, and every rural district its own peculiar - conditions and custom. The individuality of the locality and local circumstances must be taken into account.

The vital problem of zoning is to determine the needed number and kinds of districts, and where the limits of each district should fall. There should be no more differing types of districts than seem necessary to accomplish local zoning objectives. It is better to have areas allotted to business and industry too small than too large.

Protection of Highways

Zoning of rural and semi-rural areas should protect highways against detrimental frontage development. In this use of zoning, primary objectives should include the promotion of highway attractiveness, safety and efficiency through such means as concentrating business in most convenient and logical locations, and keeping all buildings well back from the roads. It is a mistaken idea that all main-highway frontage is potential business property. Excessive allowance for the business development of highway frontage in the country is as detrimental to property values and to the general public interest as is over-provision for business in any other location.

Further objectives of zoning in rural areas are the preservation of rural characteristics and the prevention of purely speculative and premature subdivision of land into streets and lots.

The town of Oak Bluffs is showing foresight in the zoning regulation which is a part of its warrant for this year. It seeks to divide the town into three classes of districts, commercial, general residential and single residential. This is a good beginning and one which Edgartown and Vineyard Haven would do well to follow. Up-Island, unfortunately, the townspeople seem to feel no need for zoning. They prefer to wait until it is forced on them rather than preparing for eventuality.

Their attitude is similar to that of a Chilmark selectman who recently gave as a reason for opposing erection of a market in a recreational section of town the fact that it might lead to zoning, and he was against zoning. In other words, he was against the one sure method of protecting the town from the very thing he was against: i. e. infiltration of new business into a non-commercial area. It is regrettable that the horse always has to be stolen before anyone is willing to buy a padlock for the stable door.

Comments