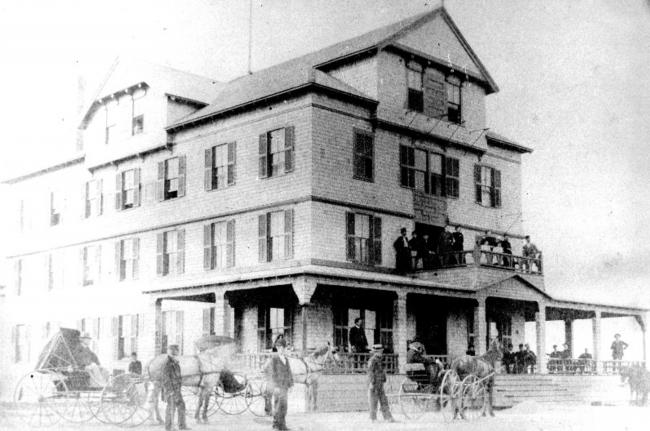

From the outside the Harbor View Hotel looked pretty much the way it always does. The lawns were freshly mowed, the stems and blossoms in the neat flower borders waved gaily in a stiff September breeze, and the sun was strong on the blues of the water around Starbuck’s Neck, on one of those recent, ideal days of early fall. However, something was definitely missing, one noticed almost Immediately. It was the porch sitters. They were all gone, and the porch furniture was pulled in. The Harbor View had closed for the winter.

What is it like the day after a hotel closes? What happens, and how does the atmosphere compare with the familiar tone of a busy lobby and dining room at the height of the season? This is what a Gazette reporter went there to find out this week. Inside, in a lobby crowded with chairs and upturned tables was Ernest Friez Jr., the hotel’s manager. He looked busy but unruffled, and he seemed to have time to chat for a while.

“Nearly everyone worked until last night and then they left. Now there’s a kitchen crew, the chef and two cooks, and several others. They’ll stay for one or two days longer.” He strolled into the wide dining room, seemingly more spacious now that every piece of movable equipment had been taken away to make room for repairs, painting, wallpapering and a new ceiling. All that was left was a long table, set for five, at one end.

A Dwindling Crew

Mr. Friez explained that this was for some of the remaining staff. “We have eighteen staying over today,” he said, “then tomorrow there will be only ten. On Saturday there will be three, myself, my wife, and the housekeeper.

“Thirty-two guests left yesterday morning before 11. After that nothing was in operation. As a matter of fact, there are still six guests who are remaining for two more days, but they are living in a cottage and not eating here.”

He led the way to the second floor and into one of the rooms, now looking barren like a hospital room. The bed and chairs were covered with old sheets and brown paper. The curtains were down and the rugs were up. It looked clean and it looked, in its barrenness, generally unappealing. “You’d be surprised how much different a room like this is when it’s fixed up,” said Mr. Friez.

He continued down the hotel’s long halls till he came to a suite of two rooms on the other side of the building, renting, in the middle of the summer, for a good deal more than twice the amount of the first room. Here again, bleakness was predominant in the atmosphere, but here and there between the brown paper wrapping you could see that the furniture was better. Nevertheless, without their furbishings, without the rugs or Venetian blinds, how could you tell what room was what?

In the hallway were long rolls covered also with brown paper. “Rugs,” explained Mr. Friez. “We vacuum the rugs and roll them up and leave them right where they are, so that there will be no question of which rug goes where next spring. The same goes for these screens,” he went on, pointing to several which had been removed from the windows and propped up against them. “Suppose someone new takes over here one year. This is to make it simple. Everything is left right where it is.”

More Rolls of Brown Paper

Down more hallways, past more rolls of brown paper, and down the back staircase to another lobby, also packed with chairs and tables, the tour continued. In the bar Mr. Friez stopped again. It had been completely cleared of glasses and bottles and lime squeezers and so on. Two long objects lay on top of the bar, wrapped in brown paper. Mr. Friez felt them inquisitively for a moment, and then said, “Venetian blinds”.

He led the way back into the huge, empty space that was the dining room, talking as he went. “Everyone takes care of his own department when we close up. The kitchen boys and the waitresses clear the dining room, the bartenders close up the bar, and the maids clean up upstairs. In that way the operation doesn’t take too long. That is, the physical part of it doesn’t. Soon now I’ll go all over the hotel checking on things that need replacing. seeing that everything is closed up properly. Like locks,” he added. “I check all the locks.”

He pushed through the swinging doors into the kitchen, where activity was at a minimum. Two cooks were at the stove, one of them cooking steaks for the staff, the other simply talking, and two girls were cleaning. “This is interesting,” said Mr. Friez, swinging open a heavy door to reveal a large walk-in ice box. In the winter this is the warmest place in the hotel, he said. “Here we store everything that might possibly freeze, even fire extinguishers,” he commented, pointing to a row of them on the floor, below gallon jars of French dressing and vinegar, and cans of onions.

The Post Cards Remain

This round trip of the hotel ended back in the front lobby at the reservation desk. There were some unsold postcards and some unused cartons of cigarettes on the desk. “The cigarettes will go back today,” the manager said, “and the postcards will stay right where they are. The switchboard will be disconnected and the water will he shut off.” He looked at the big windows across the lobby. “And we’ll put brown paper on those,” he said.

But beyond these routine procedures which seem obvious, there are other chores. A linen inventory must be taken, for instance. “The housekeeper will do that,” Mr. Friez said, “but she can’t begin until all the sheets come back from the laundry. Then we have to take inventory of silverware and glasses, etc. And I’ll be here until Oct. I doing the audit when the auditor arrives.”

Wooden battens must be put up at the hotel’s entrance, roll-warmers must be put away, the building must be made weatherproof. Mr. Friez said he is far more concerned with the weather than with vandalism. “Nobody would be interested in breaking in here and stealing a chair, do you think?”

And the kitchen equipment is given special treatment. “We scour the stoves, clean them well, and then we grease them.” said Mr. Friez. “We rub them with vaseline to protect them from rust.” and then they are covered with the famous brown paper.

There is mail to be forwarded for some time after the close of the hotel and the departure of the last guest. This season one lady left a dress, recently purchased at a shop in Edgartown. and another left a floppy old cloth sun-hat, the lining unsewn, and in general ill repair. The dress we will send on.” said the manager, “the hat we will throw away.” And two guests put money in the hotel safe and went off without it. One person left $23 and another $74. making it necessary for the hotel to write and send checks for these amounts. “I leave a note here at the desk listing the whereabouts of a lot of miscellaneous items, such as the keys to the bar, and the keys to the linen closet. Those things are written down in case someone new comes here next year, or even for myself.”

How Does It Feel?

How does it feel, the reporter wanted to know, after everyone has gone. Mr. Friez smiled and answered, “You are too busy to tell how it feels, usually, but I greet the occasion with mixed emotions. I’m sorry to see everyone go, but I’m damn glad the season’s over.”

The season is over now, and after Mr. Friez takes a last look around, checking and rechecking, and after the housekeeper leaves, there won’t even be an echo of footsteps or voices in the high-ceilinged rooms and passageways, except for an occasional tour by the watchman. A few days from now, the only sound will be the methodical ticking of an old grandfather clock which stands in the hall. The clock, once wound, takes a week to run down, and it still has a few days left.

Comments