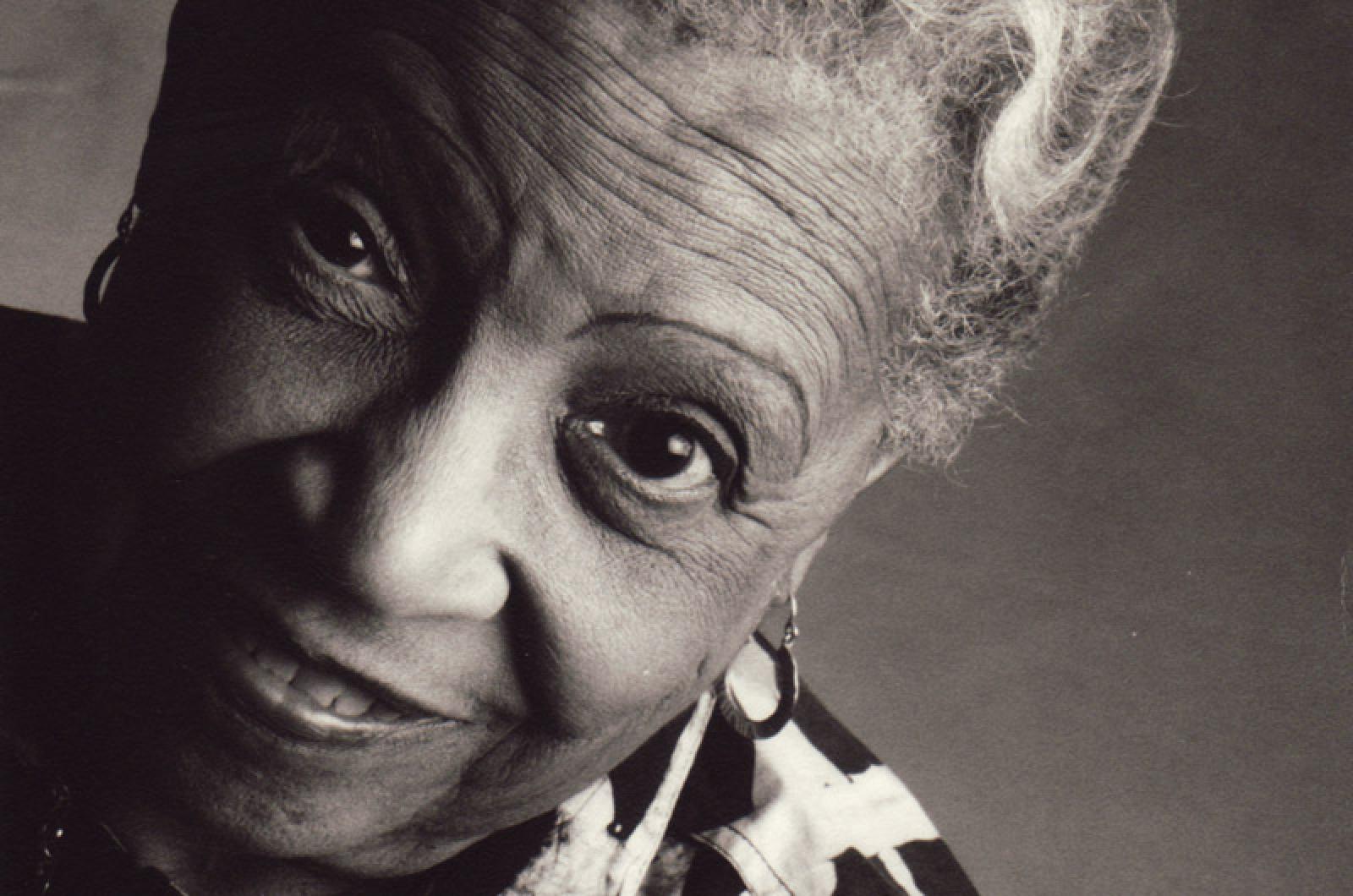

There is no end to Lois Mailou Jones’ creative resources.

The name itself is poetry. A youthful, energetic 72, Lois Jones is the veteran of a long and fruitful career in the arts. Being black and a woman, her accomplishment is especially significant.

As early as age 14, composer Harry T. Burleigh had advised Lois that if she wished to establish a serious career, she would have to go abroad in order to get full exposer and avoid the disadvantage of being black in the United States.

Lois divides her time between Washington, D.C., Haiti, and France. Fortunately, husband Pierre is cooperative about traveling, as Lois has felt an urgent need to return to the Island for the past three summers. She still stays in the family home on Pacific avenue, and her mother is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery. The soothing blue of the surrounding sea is Lois’s “strongest link to life. I feel safe here, and very much with nature.” This week, Lois is exhibiting for the first time at the Old Sculpin Gallery.

A native New Englander, Lois was born in Boston in 1905. She spent childhood summers with her family in Oak Bluffs. Her mother Carolyn was a hairdresser and used to bring Lois to the homes of her clients. It was in these private homes that Lois was first exposed to art.

“I loved the colors in the paintings and would draw contentedly for hours while my mother went about her business.”

Her early predisposition toward the fine arts was encouraged by Carolyn Jones, who stressed the importance of a career to her daughter.

Lois attended the Boston Museum vocational drawing class afternoons and Saturdays during her high school years. There she received “a very strong training in the basics.” Her first show of drawings was her on the Vineyard at the home of Mrs. Henry Ritter.

Lois also served an apprenticeship with Grace Ripley, an instructor at Rhode Island School of Design, and a noted costume designer. From ideas sketched by Miss Ripley, Lois would produce detailed renderings of theatrical costumes and elaborate headdresses. Memories of this experience influenced her recent fascination with African masks and gave rise to a professional interest in fabric design. During the summers on Martha’s Vineyard, Lois and her mother gained a reputation for the beautiful silks they would spend hours tie-dying and batiking.

Upon graduation in 1923, Lois turned down an offer to continue working in a studio of her own provided by Grace Ripley. Despite warnings that further training might inhibit her natural talent, Lois decided to accept a four-year scholarship to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts school, where she concentrated in design. At the museum, she received the highest level of professional training and was influenced by the work of John Singer Sargent. Although famous for his portraits, he is also a very accomplished watercolorist.

Summers on the Vineyard were now devoted to serious painting, and she received encouragement from many prominent black artists with whom she came in contact here, including sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller. Once, while painting at Menemsha, she was discreetly observed by Jonas Lie, then president of the National Academy of Design.

“Upon introducing himself, he said, ‘I like what you’re doing,’ and gave me some pointers on technique. I was invited to bring my portfolio to New York, which I later did.”

During a year of further study under Ludwig Frank at the Designer’s Art School in Boston, Lois pursued a successful career in free-lance fabric design.

On one trip to New York, she was waiting with her portfolio to see the director of the F. A. Foster Company.

“When he greeted me, I remarked that the fabric covering the furniture and the windows was designed by me. He said, ‘You mean you did that?’ and called others out to see this little black girl who had designed this fabric.”

In spite of her success as a designer, Lois longed to have her name connected more directly with her work and turned to painting as a more personal form of expression. As her work gained a reputation, she had offers to teach. After a two-year stint at Parlmer Memorial Institute in North Caroline where she organized and headed the art department, Lois was lured to Howard University by professor James Herring. In 1930, as an instructor in watercolor and design, Lois Jones began a 47-year career devoted to encouraging talented black artists.

Lois continued her own studies as well. It was during the summer of 1934 that she met Louis Verngiaud Pierre-Noel at Columbia. The Haitian artist was eager to absorb American culture, and Lois enjoyed showing him New York. When summer ended, they parted ways. Although they eventually lost contact, Lois never forget her handsome friend with the lyrical accent.

In 1937, Lois received a fellowship at the Academie Julian that enabled her to fulfill her dream of studying in Europe. In Paris, Lois faced none of the racial discrimination she had been subjected to in this country. She felt completely free.

Translated into freedom of expression, a loosening of style is evident in the work of the period. Although influenced by the Impressionists, Lois preferred to spend her time painting in the streets instead of touring the museums.

It was in Paris that she formed a lasting friendship with Celine Tabary. Once while painting on the Seine, the girls attracted the attention of an elderly gentleman. Pleased with Lois’s work, he offered her the use of his nearby studio. Emile Bernard, father of the French symbolist school became mentor to Lois, encouraging her work and exposing her to valuable contacts.

In 1939, Lois returned to the States, and was forced to remain here during the war. It was a productive period. Winters were spent teaching at Howard University. Occasionally, Lois would attend affairs at the Haitian embassy, and inquire after her old friend.

“Do you know the artist, Vergniaud Pierre-Noel? The answer would be yes. Then I would wedge in ‘Has he married yet?’ The would come, ‘Je ne panse pas; no he’s still single.’” A sigh of relief.

Every summer Lois could be found painting on the Vineyard. Sundays were reserved for art shows on the lawn at Pacific avenue in Oak Bluffs. Several paintings from this period are hanging in the Sculpin Gallery. Mill at Menemsha features a muted but arresting complimentary color scheme. There is very little detail, and her style is less developed than in paintings done in the 1970s of the same area.

Indian Shops, Gay Head is an Impressionist oil painting of the ever popular sunset at the cliffs. It was awarded the Robert Woods Bliss landscape prize at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1941. Ironically, it had to be submitted by a white friend in order to be considered.

Lois recalls painting in her car during a hurricane in 1944, the storm raging all around. She has several paintings of the Flying Horses in Oak Bluffs done from the rafters during the same storm.

In 1945, Lois was able to return to spend summers in the South of France, working with Celine Tabary. The Mediterranean with its jewel-like blue water held the same fascination as the Vineyard landscape.

Lois’s life and career took another turn in 1953. A surprise visit from Pierre-Noel led to their marriage several months later. Coincidentally, she received a commission from the Haitian government to paint the landscape and the people of Haiti. So began a love affair with yet another island.

Her paintings were shown the following year at the Pan American Union in Washington D.C., on the occasion of President Magloire’s visit to America. Exposure to the tropical landscape had changed Lois’ style. Her colors became more highly keyed, and her composition more Cubist in nature. Through the early 60s Lois captures the local color of the villages and the dignity of the Haitian people. She took an interest in native Haitian art, and was able to arrange shows in the States for several artists of merit. In 1969, the award research grant enabled Lois to make a complete survey of contemporary Haitian art and consolidate slides and biographical data for the archives of Howard University.

In 1971, a second grant enabled Lois to travel in 14 African nations and make a similar study of contemporary African art. The influence of the decorative, symbolic style of tribal artifacts sparked a total departure from representational art for Lois. Magic of Nigeria (1971), on view at the Sculpin Gallery, is an excellent sample of the new direction. Several stylized masks are combined with symbolic designs to form an abstract collage of decorative colors.

Lois stayed in one place long enough to be honored in 1973 with a retrospective exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts entitled Reflective Moments. Ubi Girl from Tai Region was recently purchased by the Museum for its permanent collection.

Lois Mailou Jones retired from a 47-year teaching career at Howard University in 1977. She is still organizing shows for promising artists and occasionally gives a boost to the career of a former student. Lois devotes much of her time to writing. One of the projects still ahead is to publish a book on her African research. Somehow she manages to find time for her first love - painting.

The watercolors of the past several years have taken on the two-dimensional compositional emphasis of the African masks. Wherever she is painting by the sea, colors are bold and highly keyed. The 1978 Haiti work is confident, spontaneous and drenched in sunlight.

Right now Lois is preparing for a one woman show at the Haitian Museum of Art in 1979. To that end, she may be found painting in Menemsha all week.

Comments