Hidden under scrub oak, among beer bottles, rusty lobster pots and piles of clam shells is a cemetery of forgotten souls. Only a few stones still remain, one which marks the death of young man who died at sea and was buried here along the Lagoon Pond marsh.

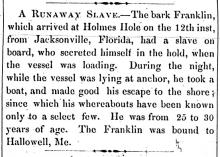

Only the Island’s oldest residents may recall this cemetery or stories about the old Marine Hospital, which is now the site of the state Lobster Hatchery. When sick sailors arrived in Holmes Hole or Cottage City, they were sent there for treatment and those that died were buried here, likely alongside the Island’s vagrants, paupers and “nonwhites.”

It was Elaine Cawley Weintraub’s search for Rebecca Michael’s unmarked grave that led her to this cemetery. For nearly eight years, the high school teacher and historian has worked on uncovering the stories of the African Americans who lived on Martha’s Vineyard with the early white settlers.

Mrs. Weintraub believes that Rebecca, the mother of the Island’s first African American whaling captain, is also buried here. And her rediscovery of Eastville will help preserve the small cemetery while introducing forgotten Islanders and sailors to those living today.

By scanning through old jail records, conducting interviews, searching for maps and reading early issues of the Vineyard Gazette, Mrs. Weintraub continues to discover more about Rebecca and her family. Many of the details will likely never be found, but pieces like the forgotten cemetery help convey a more cohesive story.

“When you lead a respectable life, there are records that traced your path,” says Mrs. Weintraub in her West Tisbury home. “But for people like Rebecca it’s hard to recreate their history because they were really on the periphery. I wanted to find out more about the life of Rebecca and finding cemetery helps me tell her story.”

That story begins in Chilmark, where Rebecca’s grandmother, also her namesake, was enslaved at the home of Col. Cornelius Bassett. The elder Rebecca was taken from Guinea in West Africa and brought to America on the Middle Passage. She spent her entire life working the farm along North Road, married a member of the Wampanoag Tribe and eventually saw her children sold into the slavery.

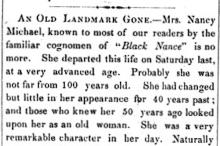

Her daughter Nancy moved to Edgartown and eventually left the slave trade. “Black Nance,” as she was referred to in her obituary, published in the Jan. 2, 1857 Vineyard Gazette, was “possessed of a strong natural mind, she acquired great influence over some of our people, by many of whom she was looked upon as a witch.”

Nancy, who lived for nearly 100 years, insisted that all sea captains visit her for good luck before departing to insure their safe return. And she was often “seen in the streets shaking her long, bony fingers at those unbelievers in her magical power and pouring fourth the most bitter invectives upon those she looked upon as enemies.”

Nancy’s relationship with her daughter Rebecca is uncertain. In an article on the early Edgartown jail in the latest issue of the Dukes County Intelligencer, Nancy is listed as twice issuing complaints against Rebecca for both stealing and not paying debts, thereby sending her to jail.

Rebecca would eventually have a son named William Martin, who would be known for breaking the racial barrier. Mr. Martin worked on several ships including the Almira and the Europa. And he later sailed as commander of the brig, Eunice H. Adams, for Samuel Osborne of Edgartown.

Mr. Martin married a Native American woman named Sarah Brown, and moved to her home on Chappaquiddick. He died Sept. 12, 1907; his home and grave still remain there. Little is known about his mother Rebecca, only that Jeremiah Pease mentioned in his diary that he attended her funeral at Eastville, which lead Mrs. Weintraub to the cemetery.

Mrs. Weintraub was first encouraged to search for stories like these while she was teaching at the Oak Bluffs School. Her students asked why the history books they studied included so few African Americans, sparking the search for their untold stories.

She found the concept that the population was concentrated only in Oak Bluffs was incorrect. Instead, she discovered that African Americans lived across the Island as slaves and even sea captains. Now a teacher at the high school, she enlists the help of high school students in her research and includes the Island’s African American Heritage Trail as part of their curriculum.

“It’s almost like this is a story that someone wanted me to tell. Everything just fell into place,” Mrs. Weintraub says.”You do have to be incredibly fascinated with a subject like this to stay interested. You go through piles of stuff and often never find anything, but you live for those moments when the pieces start coming together.”

To find the Eastville cemetery, Mrs. Weintraub sought the help of Tom Simmons at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC). Mr. Simmons found the site, which is only a few minutes away from his office at the Old Stone Building, after searching through old Island maps.

Further research revealed that the Marine Hospital was built in 1798. While in operation, the nearby yard was likely used to bury those who did not survive injury or illness. Although it appears the cemetery was used after the hospital closed, Gazette files reveal that by 1824 it had been abandoned and turned into the home of a fisherman named Daddy Richardson. Meanwhile, Samuel McCloud, who died aboard the schooner A.V. Wellington, was buried at Eastville in 1877.

Seeing the need to preserve smaller plots, Mr. Simmons is now organizing a cemetery trust. This trust will help people preserve and restore areas like Eastville without destroying valuable historical data. For example, while gravestones tell us who and when someone died, the plants around the markers show how people mourned. And often today people clear cut around old graves without assessing the foliage.

“It’s a part of the history of Martha’s Vineyard’s and no one has been proactively caring for it,” Mr. Simmons says. “The Eastville cemetery is an example of complete negligence and really a loss of history. It’s a place that cries out for proper maintenance so we don’t want to lose any more information.”

The first step Mrs. Weintraub and the cemetery trust will take is clearing the Eastville site. They invite volunteers to join them on Feb. 15 at 11 a.m. to help collect trash, prop up old gravestones, rake and clear scrub oak. Mr. Simmons also is asking those who may know of other small cemeteries or individual graves to call the MVC, so they can be part of a grave database and receive information on the proper restoration techniques.

“These types of cemeteries are all over the Island, because families were often buried in their own backyards,” Mr. Simmons says. “If we can provide some basic information, then we can clean up areas without destroying vital historical information.”

Once the cemetery is cleared and the remaining gravestones are standing, Mrs. Weintraub wants to erect a bench which overlooks Lagoon Pond. It’s here she hopes people take time to remember Rebecca and her family.

“It’s so gratifying, apart from anything else, to do this type of teaching,” says Mrs. Weintraub.”It’s wonderful to bring back the memories of people and get a sense of their lives. And by doing that, I feel we are passing through history and getting a better understanding of where we are now.”

Comments