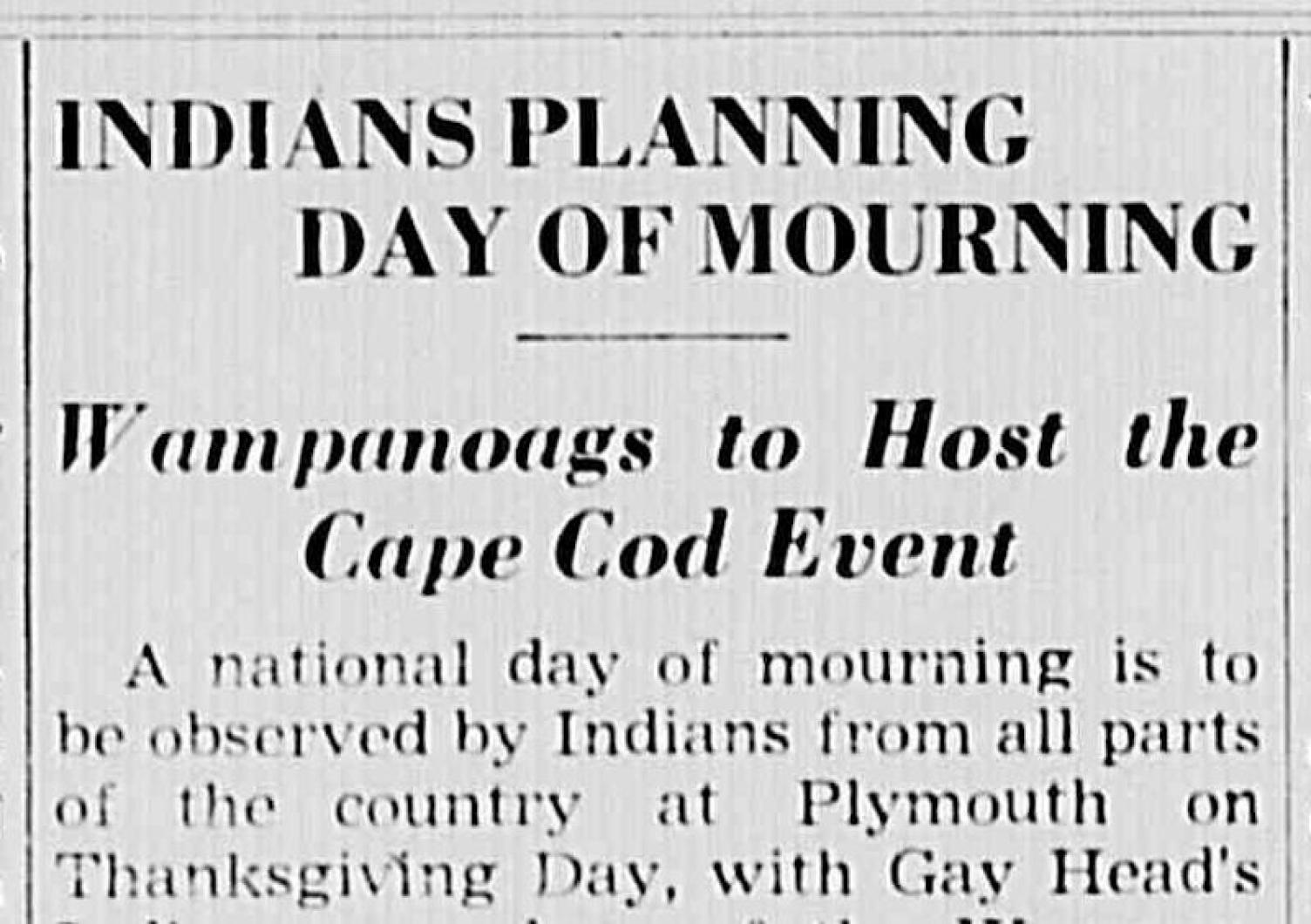

A national day of mourning is to be observed by Indians from all parts of the country at Plymouth on Thanksgiving Day, with Gay Head’s Indians - members of the Wampanoag tribe - among those serving as hosts. The solemn two-day event will begin the night before Thanksgiving at the Bourne High School and will continue until mid-afternoon Thursday, in Plymouth, when the annual Pilgrim Parade is scheduled to begin.

The demonstration, whose sponsors emphasize that it is to be a serious, restrained period of contemplation of the status and problems of the Indian since the white man’s landing in 1620, will include a visit to the statue of Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag’s at the time the Pilgrims came, an address by Lorenzo B. Jeffers, formerly of Gay Head, Supreme sachem of the Wampanoags, and a series of discussion.

Expected for the gathering are Penobscots, Cherokees, Navajos, Passamaquoddies, Cheyennes and Narragansetts, as well as their Wampanoag hosts.

All Gay Head Indians wishing to attend should get in touch with Mrs. Milton Weissberg at 645-9140, since requests for accommodations and deposits to accompany them must be made now. Contributions to help send those Island Indians who could not otherwise join the gathering are also being sought, as is help in preparing food for the weekend event.

Coordinator for the day of mourning is Frank James, the son of the late Mr. and Mrs. Francis Levitt James of Gay Head, who has become a leading figure in a statewide controversy that centered around last September’s celebration at Plymouth of the Pilgrims’ arrival.

Mr. James, a teacher of music at the Nauset Regional High School, and president of the Federated Eastern Indian League, was invited to be a guest speaker at Gov. Francis W. Sargent’s Boston banquet commemorating the Plymouth landing of 350 years ago. He readily accepted, and prepared a speech which was sent in advance of the gathering so that it could be printed for the press.

Ernest A. Lucci, deputy commissioner of the State Department of Commerce and Development turned it down and proposed, instead, that Mr. James read a speech written by a member of his department. Mr. James refused. An attempt was then made to get him to rewrite his original speech, which strongly criticized the white man’s treatment of the Indians over the past 350 years. Mr. James refused to revise, either, and so did not attend the ceremony. (Gay Head Indians who did attend, were Lorenzo Jeffers, Supreme Sachem of the Wampanoags, who delivered a short address, and Donald Malonson, chief of the Gay Head tribe.)

Mrs. James, distressed by the treatment her husband had received, and the virtual withdrawal of the invitation to play a major part in the event, wrote a letter of protest to the Department of Commerce and Development and had a copy sent to Governor Sargent. He has recently replied, regretting the controversy and expressing admiration for Mr. James’s speech.

The speech which is expected to be recited on the mourning day, follows:

I speak to you as a Man - a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by strict parental direction - (“You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community.”) I am a product of poverty and discrimination, from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters have painfully overcome, and to an extent earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed “good citizens”. Sometimes we are arrogant, but only because society has pressured us to be so.

A Heavy Heart

It is with mixed emotions that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back - of reflection. It is with heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my people.

Even before the Pilgrims landed here it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 20 shillings apiece. The pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors, and stolen their corn, wheat and beans. Mourt’s Relation describes a searching party of 16 men - he goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indian’s winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoags, knew these facts, yet he and his people welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was probably our greatest mistake. We, the Wampanoags, welcomed you the white man with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of an end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoags would no longer be a tribe.

Battles and Atrocities

What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and information - often contradictory. There were battles, there were atrocities, there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries - but never before had we had to deal with fences and stonewalls; with the white man’s need to prove his worth by the amount of land he owned. Only 10 years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the soul of the so-called savages. Although they were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other “witch”.

And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands being taken, and token reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could but only stand by and watch - while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian couldn’t understand, for to him, land was for survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It wasn’t to be abused. We see incident after incident where the white sought to tame the savage and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early settlers led the Indian to believe that if he didn’t behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemics again.

The white man used the Indian’s nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman - but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man’s society, we the Indians have been termed, “Low man on the Totem Pole”.

Fate of the Wampanoags

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokees and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoags put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man’s ways for their own survival. There are some Wampanoags who do not wish it known they are Indian for social and economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and lived among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they lead as civilized people? True, living was not as complex as life is today - but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their daily living. Hence he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life - the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decrees it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be that the image that the white man created of the Indian - “his savageness” - has boomeranged and it isn’t mystery, it is fear, fear of the Indian’s temperament.

Sachem’s Statue

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock stands the statue of our great sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man has caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of mu people are choosing to face the truth. We are Indians.

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the white did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American Prisoners of War in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting. We’re standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud and before too many moons pass we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.

We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we work toward a more humane America, a more Indian America where man and nature once again are important, where the Indian values of honor, truth and brotherhood prevail.

You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American - the American Indian.

These are some factors involved concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across the vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as the white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We’re being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have a unique culture, we still have the will and most important of all, the determination, to remain as Indians. We are determined and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only a beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours.

Comments