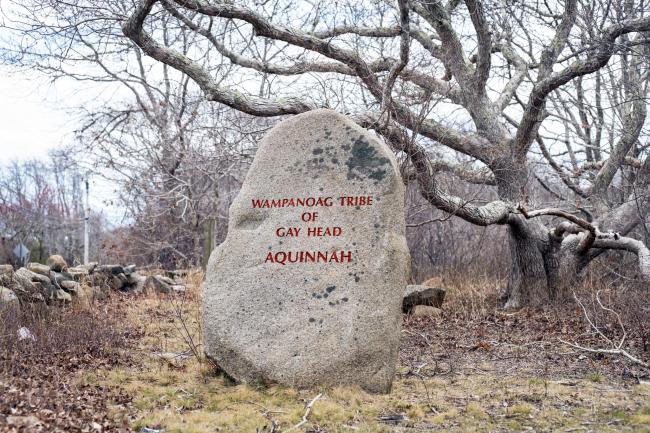

The Wampanoag Tribal Council, the Gay Head Taxpayers Association, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the town of Gay Head signed formal settlement papers in the Indian land claim suit last weekend.

The signings represent a major step toward final accord in the suit that has divided the town for nine years.

“I hope, now, we can all get together and prosper together,” said Luther Madison, tribal council medicine man and former Gay Head selectman. His comments came at an emotional special town meeting in a packed town hall Saturday night. Mr. Madison’s remarks drew applause.

Townspeople, summer and year-round, Indian and non-Indian, gathered in the town hall to vote on the settlement. Ninety-two voted for the settlement that will grant 440 acres to the tribal council and 13 voted against it.

After the meeting, officials from the town, the tribal council and the taxpayers association signed the documents. It was signed this week by Thomas R. Kiley, an assistant attorney general representing the commonwealth.

A festive mood spread through town Saturday night. The vote and the signing of the documents clearly represented an historic moment in Gay Head’s history.

Hannah Malkin, president of the taxpayers association, and Jeffrey Madison, a Gay Head selectman and member of the tribal council, shook hands warmly. In recent years these two town figures have been in fierce disagreement on nearly every political issue from the pricing of beach passes to the overriding or Proposition 2 1/2. There were settlement victory parties in a town known primarily for its sunsets, fishing, colored cliffs and political disputes.

One group, a branch of the Vanderhoop family representing virtually all the votes against the settlement, left the meeting angry.

“What do I have to gain as a Gay Head Indian from this settlement?” Thelma Vanderhoop Weissberg asked in loud and strident tones.

“Other races will call it genocide and other fancy names,” said Beatrice Vanderhoop Gentry, referring to the settlement.

“Our fight has just begun,” Mrs. Weissberg said.

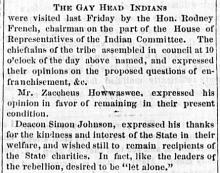

It was that group that founded the tribal council, hired Indian rights lawyer Thomas N. Tureen and filed the land claim suit in 1974. Since then they have lost control of, and this month resigned from, the tribal council. Finding the tribal council leadership too moderate, they hired their own lawyer, Robert C. Hahn, and filed their own suit. That suit claims the entire town. Mr. Hahn, after failing in lower courts, has appealed to the United States Supreme Court to have the suit heard.

But the dominant theme to the Saturday night meeting was that an out-of-court settlement is the best interests of the town.

Before the vote, Mr. Madison rose to endorse the settlement. “We feel it will lift a burden that the town has been laboring under for 10 years,” he said. “Now is the time to come together in support of the people who have given their time during seven or eight years of negotiations, and who have finally reached an agreement we feel is in the best interests of Gay Head.”

Both Gladys Widdis, president of the tribal council, and Mrs. Malkin, president of the taxpayers association, urged voters to support the settlement.

The vote was by roll call.

With agreement now from the four parties to the suit, the preliminary settlement goes to Congress in Washington and to the State House in Boston. Votes are required in both capitals before the settlement can be enacted into legislation. First there will be hearings before various committees on Indian affairs, the U.S. Department of Interior and the federal Office of Management and Budget.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the suit is how swiftly it has moved toward conclusion since July 1983, when political tensions between the taxpayers association and the tribal council peaked. Lawyers and officials from both sides said they had never been so far apart as they were last summer.

The taxpayers association took out a full-page advertisement in the Gazette, requesting money from Island residents in anticipation of a prolonged and expensive court fight. The tribal council responded with an outburst of public letters, filled with charges and counter charges as to what was the real issue and who was to blame for the apparent collapse of the negotiations.

Behind this scene the dissident group of Indians maneuvered legally to block, stall or frustrate the settlement. Members say they had to, so opposed were they to the settlement. They still are.

But the Gay Head selectmen, under the leadership of chairman Marc Widdiss, called for a special meeting in August, an informal meeting to permit all principal parties in the dispute to explain their positions.

That meeting is now seen as the key breakthrough to last weekend’s vote for settlement. Members of the tribal council and the members of the taxpayers association clearly wanted an out-of-court settlement.

“That meeting got people involved in an emotional way,” said Michael Stutz, a lawyer for the taxpayers association, and one of over a dozen lawyers involved in the dispute.

The consensus for settlement last weekend followed a flurry of work between lawyers representing the main parties in the dispute.

Why was so much accomplished in the three months after the August meeting, and apparently so little in the preceding seven years of negotiations?

Lawrence H. Mirel, attorney for the taxpayers association, says division within the tribal council delayed agreement on a settlement and stalled the talks.

Mr. Taureen, attorney for the tribal council, blames the negotiating impasse on divisions within the taxpayers association.

Mr. Mirel believed there weren’t enough face-to-face meetings between the two sides.

Mr. Tureen things there were too many. He says the issue “had to ripen at its natural pace.”

Mr. Mirel believes the first state appointed mediator, Albert M. Sachs, then dean of the Harvard Law School, was too busy to give the necessary time to the Gay Head dispute.

Mr. Tureen says the present accord is the proposed Sachs settlement. Time was required for everybody to see that the Sachs agreement made sense, according to Mr. Taureen.

Despite their many earlier disagreements, the two key lawyers now agree with the assessment from Mr. Kiley, first assistant state attorney general, specifically that the federal district court was tired of endless delays in the suit. Judge John J. McNaught was ready to push for a trial date, and nobody wanted that. The lawyers knew that all along. And that view was reinforced dramatically in the August meeting.

Accordingly, the settlement, which grants 440 acres to the tribal council, provides the Indians with properties for economic development which resolves around fishing and shellfishing, and makes available properties to build about 90 Gay Head Indian homesites, is close at hand. It is the settlement that grants to the taxpayers association guarantees against any further land claim suits in the future. It is the settlement that maintains beach rights as they are now. It is the settlement that finally will help to clear clouded title to land withing the township.

“It is a settlement,” Mr. Mirel says, “that gives the people in town the ability to talk to each other again.”

And on that point, Mr. Tureen concurs. “It will give people the opportunity to work together.

Comments