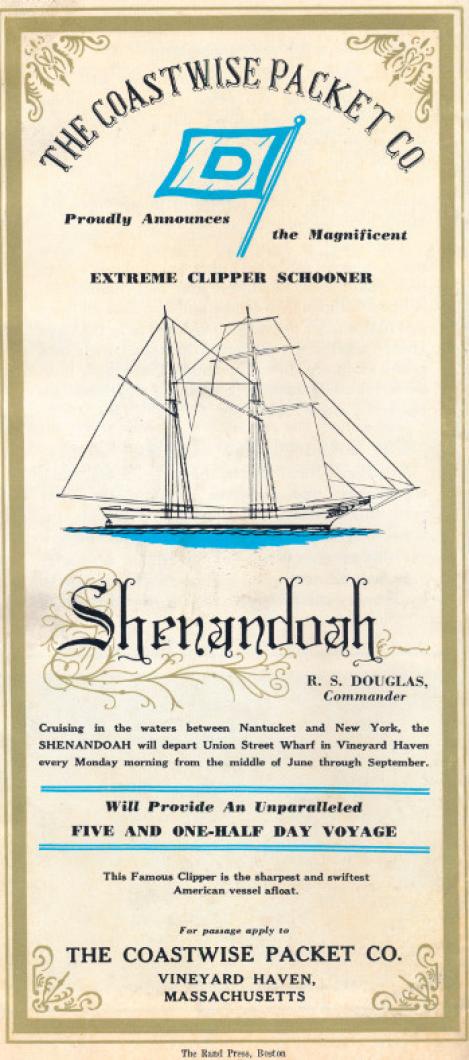

The extreme clipper schooner, Shenandoah, Capt. Robert S. Douglas, master, arrived at her home port, Vineyard Haven, during the weekend, and is due to sail this week for the Atlantic Ocean with her first passenger list. Named for a U. S. revenue cutter built in 1849, whose hull design and rig have been closely followed, the Shenandoah symbolizes all that was beautiful, judicious and distinct in the sailing craft that made America famous on the seven seas.

A design closely related to the pre-Revolutionary Baltimore clipper, and rigged in very similar manner, she is fore-and-aft rigged throughout on her mainmast, but carries a square tops’l and top-gallant on her fore-topmast, with a third yard slung below the tops’l to carry the sheets. The “85 Tons Net,” carved deeply into her main beam, attests to the fact the she is a real ship and not a plaything. A vessel of the type that sailed out of American seaports for generations, as pilot boats, slavers, smugglers, blockade-runners and privateers, all of which played important parts in different phases of American history.

As a revenue cutter, by which is first of all indicated an armed ship, she is not arranged as a cargo-carrier any more than the vessel for which she is named. The original carried a heavy gun in her waist, capable of being trained well forward and aft and to either side, but the hold was designed for the carrying of ammunition and stores for the large crew which was required.

This Shenandoah is arranged for the carrying of paying passengers, and her “ ‘tween decks” staterooms of attractive size and appointment, a saloon-like dining room and all other accessories which make for comfort and pleasure in ocean cruising. Plainly, below and on deck, she is all ship, massively constructed, but with the racy lines and rakish rig that characterizes the pirate of tradition. Dependent entirely upon her sails for propulsion, she carries a diesel-powered yawl-boat on her stern-davits, which can tow her around in calm weather or assist in docking, and her two lifeboats are the famous Whitehall-built craft, used as water taxis in the days of Queen Elizabeth, and imported to this country where they were improved in design, and used for similar purposes in the early days of New York city. The traditional ship’s gig, often mentioned in sea stories of other days, was constructed upon these lines, as being an easy-pulling boat and not burdensome.

But it is of her rig and working-gear that one would speak who recalls old-time sailing ships and loves them, for there is virtually nothing about this vessel that does not hark back to a century ago or close to it. Though all is new and of the finest quality of materials and workmanship, she might have been built and rigged by John Cannon of the Bass Creek shipyard a hundred years ago.

Extreme Rake of Masts

Noticeable first of all is the extreme rake of her masts, supposed to add speed, as it probably did. Her short bowsprit supports the old-style flying-jibboom, which was required in many ports. The idea was that ships and vessels docking bows-on, as might be necessary, their bowsprits either took up needed room in a slip, or projected out over the streets ashore. Therefore, there were regulations that flying-jibbooms be carried and that they be “housed” when in dock, in order that they might not interfere with land traffic, particularly loads of hay. New Bedford, the old whaling port, has such an ordinance among its by-laws to this day.

Her windlass is the powerful hand-operated and double-headed type, used on whalers such as the Charles W. Morgan, without the “wildcat” which comprised the “Swedish patent” later adopted. Gangs of men pump at the brakes in order to turn the barrel in hoisting or lifting the anchors, and it is observed that there is much wood used in the construction of this windlass, which is designed for winding-in either chain or hempen cable.

Aloft, on her foremast, stands that maze of running-rigging always associated with yards on ship, barque, brig or barkentine. The two upper yards are on parrels, devices that make it possible to raise or lower them on the topm’st. The lower yard, which carries the tops’l-sheets, is on a krantz-iron, exactly as the lower yards of whalers were slung. Such a device allows the yard to be lifted or swung into any desired position.

Standing rigging is not manila as was the case aboard the original Shenandoah, but of wire, yet Captain Douglas is too fervent a lover of old ships to set up his shrouds with turnbuckles. Instead, the wire stays terminate in deadeyes, spliced into the rigging, and these are “set-up” to her chain-plates by means of hemp lanyards, rove through the deadeyes.

Massive fife-rails stand around the foot of both masts, carrying the rows of belaying-pins to which sheets, halliards and braces are “belayed,” or made fast, each line assigned to its own particular pin where it can be located in pitch darkness by the sense of touch.

Three more features, which hark back indefinitely: her turned “dolphin-striker,” acting as a truss beneath her bowsprit, her hand-operated bilge-pumps, and her tall, wooden wheel, bright with varnish. Truly the Shenandoah is a living thing, a beautiful creation, the product of man’s hand and brain that even in repose alongside of her dock conveys the impression of strength, speed and grace.

Comments