Four hundred thousand dead civilians and 2.5 million displaced refugees. Hundreds of undefended villages razed by government-funded marauders on horseback. People living in camps with poisoned wells. Starving two-year-olds who look like they’re 102. Mothers who send their daughters out to collect firewood, knowing they will be raped. The violence in Darfur makes the early 21st century look as dark as the 20th.

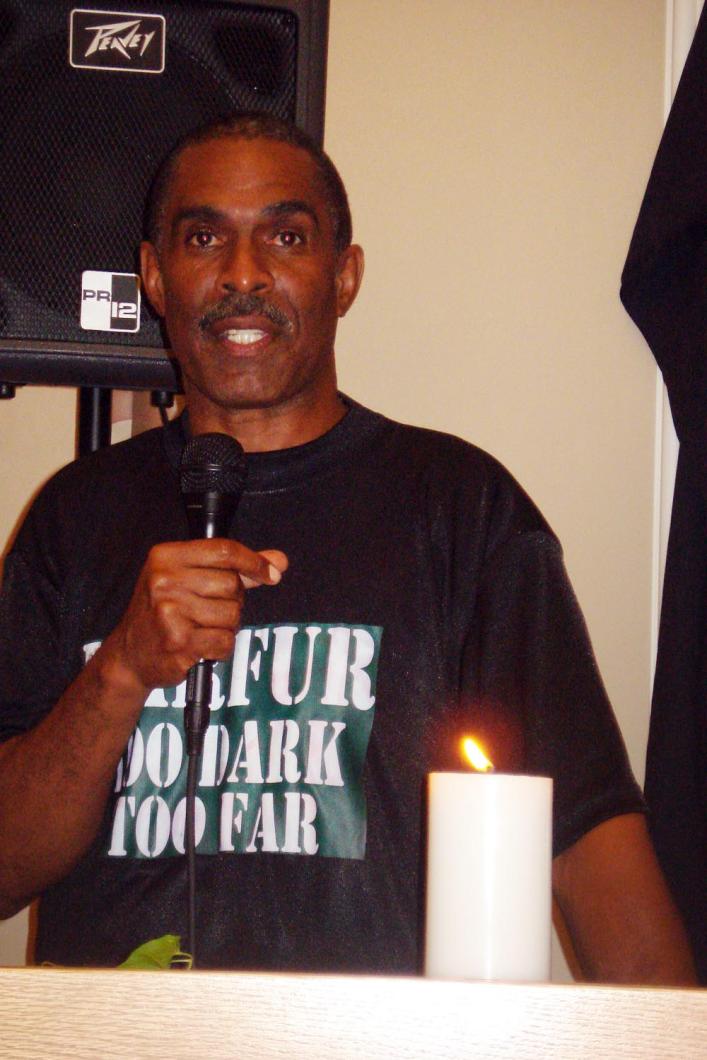

Recently, Hafiz Farid screened his documentary, Darfur, Too Dark Too Far, to an audience at the Oak Bluffs Library. Through his film, Mr. Farid hopes to raise awareness about the atrocities in Southern Sudan, but also to draw parallels between the root causes of the murders there and other genocides through history around the world. The film’s fundamental thesis is that all genocide is based in racism, and that history is doomed to repeat itself if we do not recognize this common thread.

Darfur is an area of Western Sudan which, since 2003, has been subject to massively disproportionate government reprisals against a rural populace that may be supplying rebel fighters who seek to destabilize central rule. The residents of Darfur are darker skinned than their attackers, who are generally from Arabic speaking nomadic herding tribes. Many speakers in the film attest that the Arab Sudanese see themselves as racially superior to the darker-skinned Darfuri people.

According to savedarfur.org, a group trying to ameliorate the crisis, the conflict may have its roots in overpopulation, desertification and resource depletion that have caused extreme territorial pressures in the past few years. The merciless quality of the violence — strafing by helicopters, horseback raids, rape, dismemberment and well poisoning — perpetrated against defenseless villagers indicates a human impulse far worse than greed.

As one man, a survivor of the Armenian genocide, says in the film, “Mankind is the worst animal in the world. Animals kill to eat. Humans kill based on a difference of religion.”

Hafiz Farid believes the murderous impulse, the root cause behind the violence, is racism, and he sees it as a disease that needs treatment through education, “Diseases have to be broken down,” he said during a question and answer session. “They have to be examined and understood. This film is a process of dealing with root causes.”

Perhaps the most potent evidence of how racism plays into the story is the slow response from developed nations to intervene in the conflict. Simon Deng, an activist who himself is a victim of violence in Sudan, puts it this way: “If this had happened to white people, we would have gone to World War Three.”

Though many documentaries are coming out dealing with the genocide in Darfur, Mr. Farid’s film draws comparisons between the contemporary atrocity and historical ones, including the Holocaust against the Jews, the Armenian genocide, the Cherokee Trail of Tears and institutionalized slavery in the United States.

The comparisons between conflicts so disparate in time, place, and cultural specificity might be a bit simplistic, but many audience members found this element to be the film’s strength. “The power of the film was the weaving together of different historical events,” said Ricki Lewis, adding: “It’s happened before, it’s happening now and it will happen again.” Larry Lewis another member of the audience, expressed concern at the general ignorance of Americans and their fascination with trivial hype. “If you’re more interested in what happens to Michael Vick than what’s gong on in the world, you’re living in Brittney Spears land,” he said.

Darfur Too Dark, Too Far is hard to take. The editing alternates between poorly shot interviews with bad sound and horrifying images of corpses, dismembered bodies and starving children. At times the film seems to lose its focus and does not address what might be done politically to end the conflict. What saves the film is its good-heartedness and the commitment of those who participated in its making to bettering the desperate situation in Sudan.

Cong. Donald Payne, a Democrat from New Jersey, appears in the documentary and was also in the audience. He took questions during a period of technical difficulties with the projector.

After the screening, Congressman Payne talked about his work to try to bring attention to Darfur, which includes putting forward a resolution in the House that declared the situation genocide. “We were hoping there would be more positive action after the resolution,” he said, “and I am personally disappointed that the situation is deteriorating. We need to put pressure on the [United Nations] and the Arab League to be involved in funding.” He added: “Our government is too soft on the government of Sudan because they claim to be helping us in the war on terror and we don’t push China due to commercial ties. As a member of the U.S. government I am frustrated by the influence of these contravening forces.”

China is Sudan’s largest trading partner and China National Petroleum Corp. has a 40 per cent share in the international group extracting oil in Sudan, according to the Brookings Institute. Chinese companies have sold the Sudanese government war planes and helicopters, according to Amnesty International.

One way activists are trying to influence the Sudanese government is through divestment. Congressman Payne’s brother, Bill Payne, persuaded the New Jersey treasurer to divest the state’s pension plans of companies who do business in Sudan. “At first the state treasurer thought we shouldn’t mix social policy with fiscal policy, but I convinced him that the money our funds were earning was dripping with blood,” said Mr. Payne.

Mr. Farid used music to soften the effect of so much brutal imagery and underscore the emotions of the film. “Someone once said, music is the fragrance of your film, and there is a sweet fragrance to this film, and the strength and the truth of the people is what make this film engaging and not repulsive,” he said.

The film ends with So Far Away by Carole King, a lamenting love song about someone who has moved on. The song is played over images of refugees trudging on dirt roads to an unknown, hopefully safer destination. “Carole King is one of the most incredible songwriters. Her songs transcend black or white — that particular song includes the words from our title — are we not concerned because these people are too far away, or too dark, or is it the darkness of ignorance? It’s a love song, and in terms of this situation, that’s what’s missing, and it’s that powerful force of love that will help us act and move to another level,” Mr. Farid said.

More information about the crisis in Darfur can be found at savedarfur.org. Information about the documentary can be found at darfur2dark2far.com.

Comments

Comment policy »