Driving down Edgartown’s School street with lamp-maker Billy Hoff is like a scene from Men In Black — except that, instead of aliens, you see that lanterns handmade by Lamplighter Corner Inc., are right under your nose, and absolutely everywhere. “That’s a bullseye pane,” he says, steering his pickup past a blue-front glass piece on a three-foot high solid brass lamp. “There’s another couple . . . I made that one. Oh, there’s one.” It turns out that almost every house in the district has been quietly adorned with his company’s 19th century gas lamp reproductions.

Responsibility for this lamp ubiquity lies primarily with founder Hollis Fisher, who lived and worked out of School street in the 1960s. But it is on Indian Hill Road in West Tisbury that Lamplighter Corner Inc. has its unassuming new headquarters, in a single room at the back of Oak Leaf landscapers, a company owned by Mr. Hoff’s brother and business partner John.

“You’d have to be coming out this way with our destination specifically in mind to stand a chance of finding us,” Mr. Hoff, 40, readily admits. “I haven’t even put up a sign.” Evidently footfall is not a priority.

Two skylights in Mr. Hoff’s attic workshop-cum-showroom reveal a stark view of the now leaf-free West Tisbury woodland. Neatly stacked boxes of washers, name tags and lag screws line the back wall and a dozen lanterns, made to Hollis Fisher’s specifications, decorate most of the surfaces. With Native American names like Mattakesett and Nunnepeg, they range in price from $450 for a small Katama to $850 for a large Edgartown Street. Mr. Hoff and his 19-year-old assistant Aloizio Vargas sit side by side on work stools — Aloizio tinkers with a pane of glass on the workbench, periodically shifting in his chair to listen in, the glass resting in his lap while his boss explains the origins of the business. Mr. Hoff’s conversation is staccato and he rarely amplifies a point unbidden — perhaps a consequence of the scantly populated working environment — but his passion for his craft, which he spends nearly ten hours a day practicing, is clear.

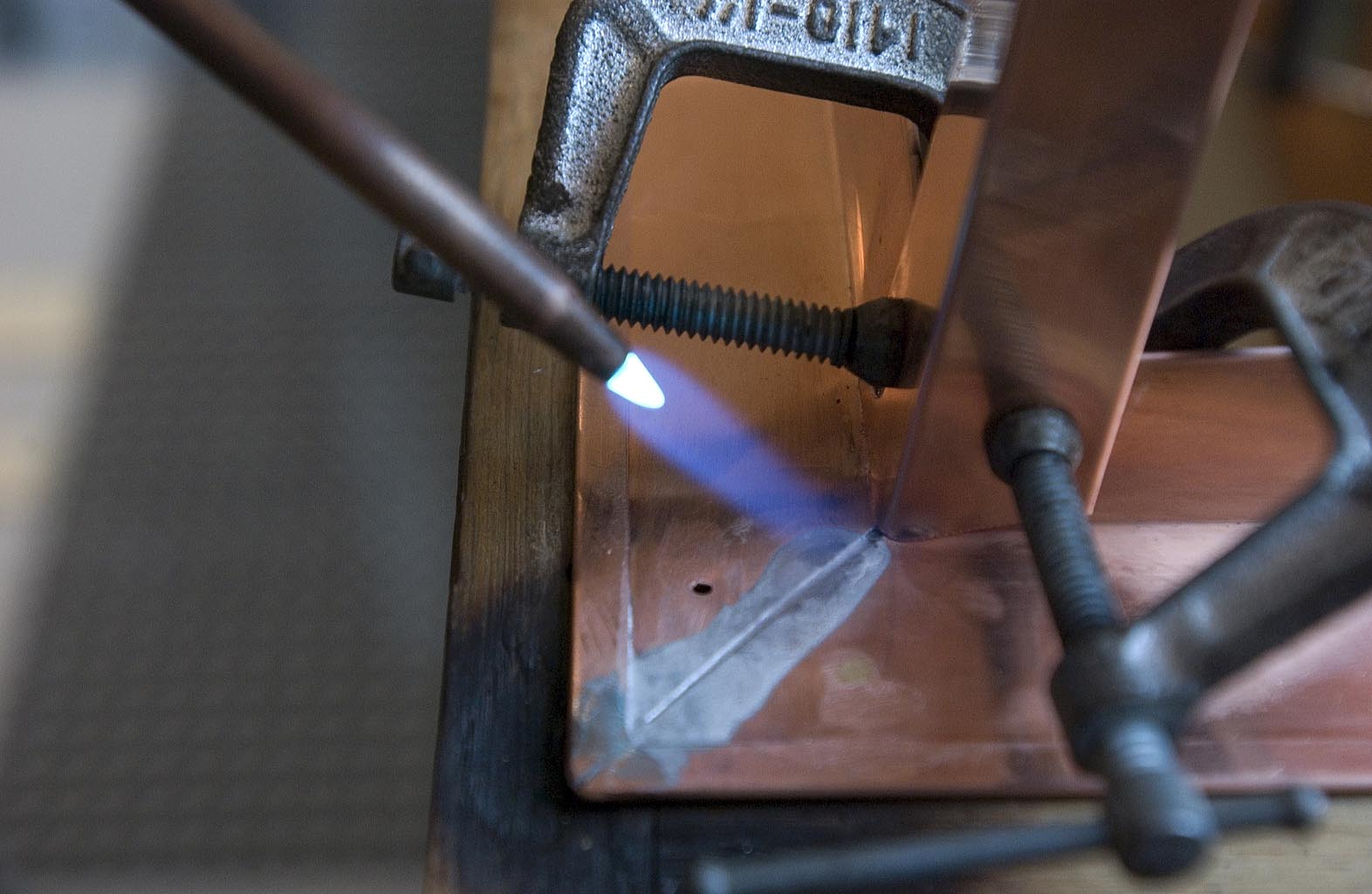

Starting out with eight-foot-by-one-foot copper sheets, Billy and Aloizio work through a series of wrought-iron machines, all pillaged from Hollis Fisher’s workshop. Ten-inch rectangular lengths and curved copper strips are cut out on a foot shear, crimped using hand brakes and then fitted with glass cut-around templates Billy has scissored out from cardboard. An old soldering iron and rudimentary drill press are the only two pieces of machinery with moving parts in the quiet workshop.

Billy prefers it that way. “If I had new stuff, I’d be pressing a button to cut the copper, instead of stepping on the foot shear,” he says. “There’s no assembly line this way and every lamp is going to be different.”

Working together, with Billy on the precision work and Aloizio assembling, the pair can crank out a lamp a day. During the summer, the waiting period on an order can be up to five months, so in the winter months the pair works to close the gap.

Born in New Jersey, Mr. Hoff met his future wife Amy as an undergraduate at Ithaca College. When he went on to study fine art at Chicago Institute, the two split up. But they met again in New York when Billy was in Brooklyn, working “schleppy” jobs. Walking his pet huskie through downtown Manhattan one day he bumped into a stranger with two huskies and a lamp design business. Her friend was looking for someone to help design and manufacture her lamps. Billy claimed experience (though at that point it was negligible) and landed the job.

When his wife became pregnant in 2001 they decided to leave town. Mr. Hoff had been coming to the Vineyard since the late 1980s, summering with friends. His mother bought property here. His brother moved over and founded a landscaping operation in 1994. The Island was the obvious choice, and Mr. Hoff says so far he doesn’t miss the city at all. “I mean I like to go to art shows,” he says, driving down Indian Hill Road in his Island-seasoned Toyota. Canopied by denuded scrub oak and entirely deserted on a Tuesday morning, it feels a long way from New York. “You can see most of that stuff online now anyway.”

He has two children (ages two and six) to support and a mortgage to pay. Still, Billy doesn’t want the business to change scale. “It’s little more than a one-man operation and I like it like that,” he says. Mr. Hoff feels his business is helping to preserve Island enterprise. “There’s an element of custodianship,” he says. “It’s a quintessential Island business and it’s good for it to continue.”

In addition to the reproduction lamps Billy is looking to introduce some modern designs. This is where he channels his artistic impulses. He points up at a squatter, more symmetrical lamp hanging from the ceiling, noting its cleaner lines and absence of a gas lamp door. “I don’t want to just drone these out,” he says of the original lantern designs.

Mr. Vargas has been working for Mr. Hoff for the past six months, and has quickly learned the production process. Listening attentively to his boss, his own answers are spare. “I just work, go to church and go home,” he says with a wide smile. Billy opens the shop at 7:30 a.m. and closes at 5 p.m. Between these hours, he and Aloizio are holed up in one main room with a small annex for cutting glass; they share the inside banter and insult-trading that comes from working together in close quarters. Mr. Vargas, who spent his first 16 years in Brazil, is steeling himself for the winter months when they will arrive at and leave the shop in icy darkness. “Look, it’s depressing,” he says, gesturing at the shop’s view of bare foliage. He’ll tough out the cold listening to gospel music on his iPod to drown out Mr. Hoff’s Bob Dylan albums and books on tape. Mr. Hoff gave him time off last week to go to Boston, where he performed in his Vineyard Haven church’s choir. “I let him out early for that,” he says. “I’d give him days off anyway, but he just likes going to church.”

The Lamplighter business started in 1967 when Hollis Fisher had his leg crushed in a car crash. During a long and painful recovery, Mr. Fisher found solace in his cellar workshop tinkering with copper and repairing gas lamps from the neighborhood. Hitting on the idea of making a replica lamp, he produced one using original methods and materials. His single concession to modernity was an electrical fitting with an incandescent Belgian light bulb attached, in place of gas power. When Mr. Fisher hung his prototype over the doorway, neighbors began asking for their own; a business was born. While the business has always relied on Island word of mouth, orders come from across the country and from visitors who see the lanterns as a piece of Edgartown they can take home.

Last October Billy and his brother bought the company from antique dealers Tim Rush and Tom Fisher — who is Hollis’s son — who had run the business out of their Edgartown shop, Rush & Fisher, since the late 1980s. They still stock a range of the lanterns, which look at home next to genuine relics of their antiques dealership. The Hoff brothers made the purchase when John heard that Mr. Rush and Mr. Fisher were looking to concentrate on antique trading. Billy, who had been working at the landscaping business, spent the following three months training at the hands of Tim and Tom and learning the runnings of a small business. Billy says their help has been invaluable. “Although there’s nothing in it for them,” he says, “they always help people when they come in and direct customers my way.” Mr. Rush and Mr. Fisher will stop selling the lamps at the end of next year, when their contract with Mr. Hoff runs out, at which point Billy will need a new retail strategy.

“They’re great at meeting people,” says Billy, admitting that courting clients is not his strong suit. “There’s something great about losing yourself in the craft,” he says, and checks himself, laughing. “That sounds antisocial. I’m going to have to work on the schmoozing side of things.”

Lamplighter Corner’s works will be at the Artisans Festival this weekend.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »