Think of a someone older than dirt. Someone you would never expect to have made a discreet visit to Martha’s Vineyard. Someone who has political problems with religious fundamentalists.

No, not John McCain.

We’re talking about a woman, remarkably well preserved considering all she went through, often referred to by a single, four-letter first name associated with John Lennon and the Beatles.

Nope, not Yoko, either.

The name we’re looking for is Lucy.

It is a name familiar to most people with even a passing interest in paleontology and the evolution of our species, for it refers to one of the most famous fossils in the world, the 3.2 million year-old, 40 per cent complete skeleton found by Dr. Donald Johanson in November 1974 in Ethiopia’s Afar depression, and named by his then-girlfriend, who had been listening to the Beatles album Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band.

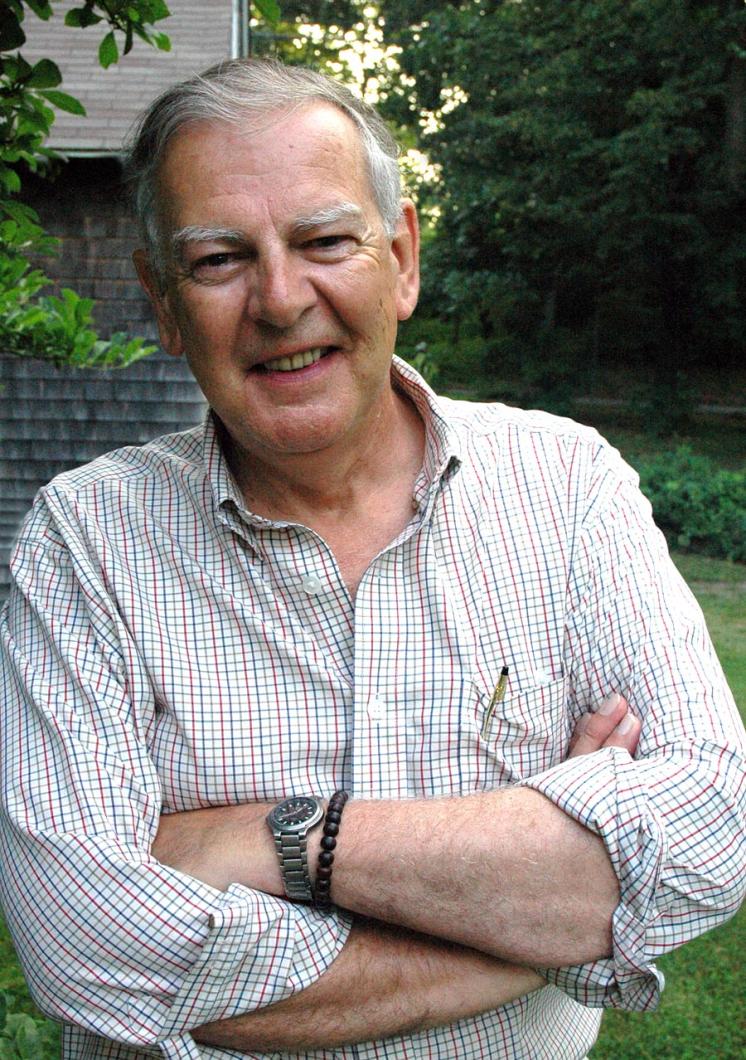

Dr. Johanson was the first guest speaker in the Wednesday night Summer Institute series at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center, on the last three million years of human evolution.

And in his presentation, he revealed the surprising link between Lucy and this Island.

Not that the Vineyard had anything at all to do with the evolution of our species, but it did apparently have a role in Dr. Johanson’s evolution as a popularizer of the generally-dusty discipline of paleontology.

He came here in 1980 to visit the late Maitland Edey, who lived at Seven Gates Farm and who began the Time Life book series, and talked to him about a book he hoped would interest people other than the scientific community in the crucial link between apes and modern humans, formally known as Australopithecus afarensis.

“It didn’t take Mait long to tell me it was dreadful,” he recalled.

And so they collaborated for more than a year crafting Lucy: the Beginnings of Human Kind.

And, inter alia, he said, parts of Lucy came here, in secret.

“I made many trips during that project. I brought several bones of Lucy with me while I was writing the scientific monograph describing the jaw and teeth,” he said.

“So Martha’s Vineyard has played a very, very important part in my history.”

That was nine books ago — the latest is entitled Lucy’s Legacy — but that first one is still dearest to his heart, and the one which he said nearly all his graduate students tell him helped inspire them to get involved in evolutionary studies.

And why would the story not inspire a would-be fossil hunter?

As he recounted it, Dr. Johanson, a very young scholar aged 31 in 1974, with a newly acquired PhD, set off to Ethiopia, to the Afar triangle, a largely unexplored part of the Rift Valley, and found in relatively short order “probably the best known hominid fossil discovered in the last century.

“She’s very close to what we think of as the missing link,” he said.

Lucy had what he called an amalgam of characteristics that put her between the apes and modern humans.

“She sits, her species, at a pivotal place on the family tree, between things that are essentially upright apes and the lineage that emerged as modern humans.”

In a fascinating address with accompanying slide show, he walked his audience not only through that chance discovery — how while walking on Nov. 24 he glanced over his shoulder and saw a glint of bone — but through the history of evolutionary study and the most recent developments.

And he reminded everyone also that while human evolution can now be traced back even beyond the 3.2 million years to Lucy, the first human understanding of the process of evolution is only a century and a half old.

He noted that we have just passed, on July 1, the 150th anniversary of the day Charles Darwin’s first paper propounding the theory of evolution, along with another Russell Wallace, were read to Linnean Society in London.

“It really marks the beginning of this year-and-a-half-long celebration of one of the great ideas in intellectual thought,” he said.

“And that is evolution by natural selection.”

Dr. Johanson described Darwin’s realization as: “The best example I can think of is that bumper sticker: ‘The mind is like a parachute: it only works when it’s open.’

“Darwin left England believing in the fixity of species and returned from that expedition believing all life has indeed changed.

“What was so prescient about Darwin was that he understood it was not directed, that there was nothing really in terms of a goal in the world of biology.”

He noted Darwin, right back then, thought Africa was likely the place to find most ancient ancestors to human kind, on the basis of anatomical similarities between us and chimpanzees. Modern genetics had proven him right; there is only a 1.5 per cent difference in DNA between humans and chimps.

The acceptance of Darwin’s belief that Africa was the cradle of humanity was even more recent. When an Australian anthropologist Raymond Dart discovered the first Australopithecus fossils in South Africa in 1924, he was so criticized that he gave up his endeavors.

The Eurocentrism of biological science at that time would not accept our ancestors came from the dark continent.

But Africa was, and remains, where most of the action is.

He spoke not only of Lucy, “the benchmark by which other discoveries are assessed,” but also of further scientific discoveries which are filling in the blanks in our development.

Lucy and her kind were probably about three feet tall and largely herbivorous, certainly not hunters. But in 1992, a fossil was found along with the first evidence of stone tools, with which our forebears were able to hunt.

And just as Africa produced our remote relatives, so the evidence now was showing it was the place where the first truly modern humans appeared. In southern Africa now, scientists have found evidence of people using ochre paints, specialized tools and other artifacts 160,000 to 200,000 years ago. Compare that with the celebrated cave paintings at Lascaux, France, which are maybe one-tenth that age.

“What a revolution is going on at the moment,” he said, showing a likeness of one of these people.

“This is probably what the first Europeans looked like, coming out of Africa with a unique way of looking at the world, manipulating the world . . .”

And coming to dominate it.

Understanding how we came to evolve, he said, was vital in understanding our place in the natural world and our responsibilities to it.

“For as astonishingly frightening as it sounds, we are the species in control,” he said.

It remains his hope that we will evolve into a more reflective species, and not “homo egocentricus.”

So we will leave descendants who will be able to look back on their origins.

Comments

Comment policy »