The Internet did not arrive on the Island by chance, like the skunk and the raccoon. It was deliberately brought here by an anxious group of like-minded computer enthusiasts. Twenty years ago, it wasn’t even known on the Vineyard as the Internet.

Today, business on the Island doesn’t get done without a byte or a bit being exchanged. The Internet today is in every town hall, most municipal buildings and in just about every household. The world is linked to the Vineyard and the Vineyard is linked to the world.

Like most New Englanders, Vineyarders often have been reticent at the introduction of anything new. But when it came to the Internet, a lot of Islanders wanted it faster than the utilities could offer it. Vineyarders still may not want a stop light on the Island, but early on they wanted a digital information version of Grand Central Station.

And while today it may take days to send a letter through the post office from one end of the Island to the other, it takes fractions of a second to send an e-mail from the Island to anywhere in the world.

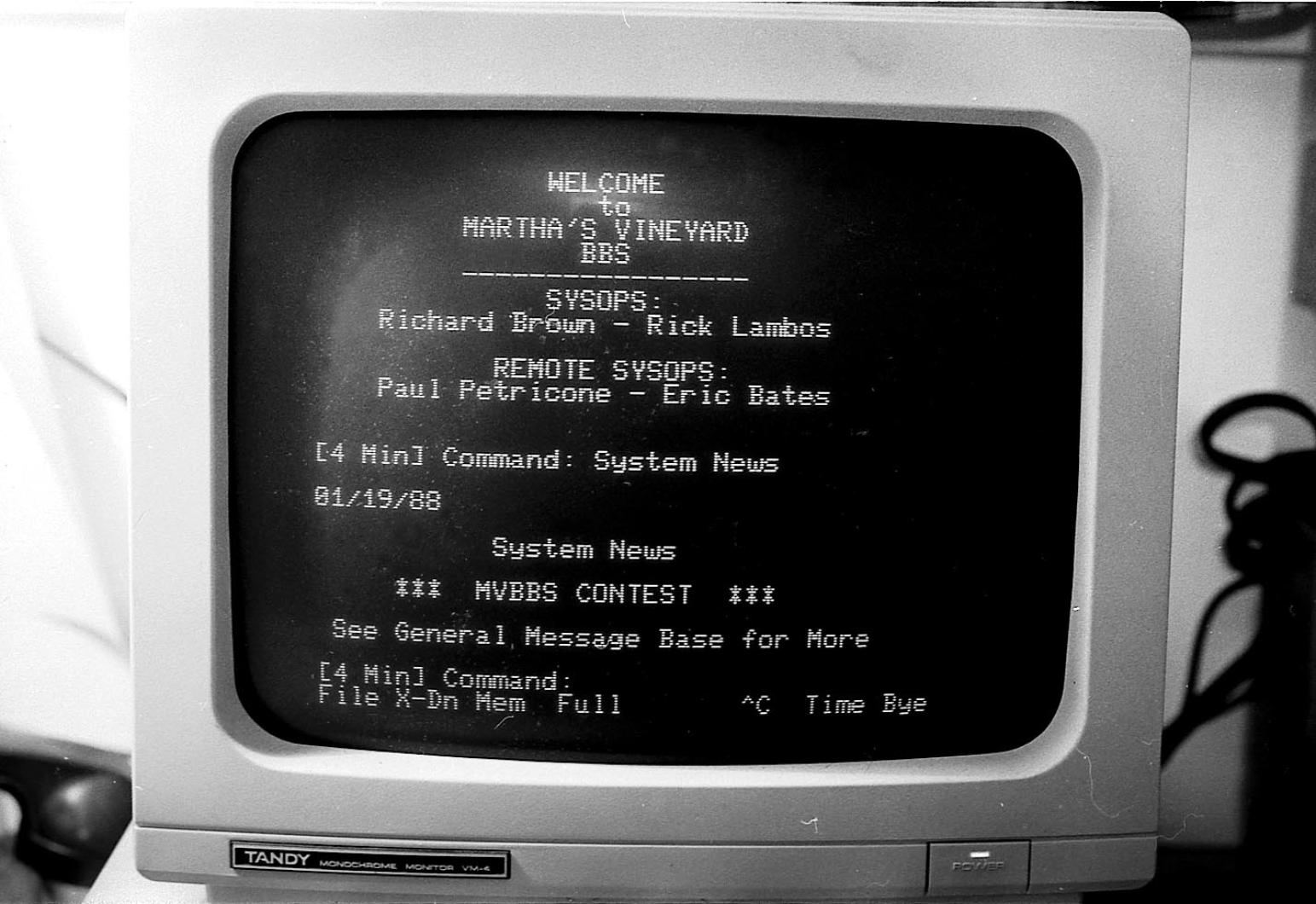

Islanders pretty much agree that the first sign of the Internet on the Island was initiated by Richard A. (Rick) Lambos and Richard (Dick) Brown, both of Edgartown, when they started the Martha’s Vineyard Bulletin Board in November of 1985.

Back then, Mr. Lambos was exploring ways to keep in touch with his mother Meg (now deceased) who had lost her hearing and lived on the mainland.

Computers then were primitive, unimaginably simpler than the plug and play computers of today. They were difficult to work. Making a connection by telephone was hard.

Martha’s Vineyard Bulletin Board had one dedicated line that was open to anyone with a like-minded modem. In those days computers had a words-only screen that barely could show letters and numbers. Many users got their first pair of reading glasses using these computers.

“For those of us who chose to be on the rock, it gave us an avenue to connect to the rest of the world,” said Mr. Lambos, 56, a registered nurse who works at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital as an emergency room staff nurse. He reflected back on the early computer days.

Twenty years ago he had an Atari computer. The bulletin board provided a place for computer user groups to chat, to share in the knowledge. There were MacIntosh, Apple and IBM computer groups. Even Radio Shack computer owners had a place.

Word got out, and people would log into the Vineyard bulletin board from afar — places like Hawaii and Nantucket.

When the Vineyard Gazette wrote a story about the service, the calls came in from around the country. The most popular information request was for the Steamship Authority ferry schedule. Mr. Lambos recalled keeping the times current.

Since the bulletin board was free, visitors could also practice their computer skills without cost and then log into the pay-as-you-go online services like CompuServe, Prodigy and the newest arrival, America Online.

The bulletin board also had a small collection of free downloadable computer games. The modem operated at 300 or 1,200 baud (that is, bits per second), which today is unthinkably slow. The bulletin board claimed to have 60 users.

I remember those years. In 1985, Radio Shack brought out the TRS-80 Model 100 portable computer. Journalists quickly adopted the machine. It was the predecessor to today’s laptop. The screen measured but a few inches and it ran on four AA batteries. There were primitive spellcheckers and software inside.

Journalists and computer geeks nicknamed the little machine the Trash 80. Writers could go online, check message boards like Martha’s Vineyard Bulletin Board, and send e-mail and download wire service news stories from online services. For me, it was the first way I could send copy to editors afar.

In February of 1991, Mr. Brown and Mr. Lambos announced to the world in a Vineyard Gazette article that they had received their 10,000th caller. It was Alan Muckerheide of Oak Bluffs. He had been a bulletin board member for two years. The board claimed 171 members.

The Martha’s Vineyard Bulletin Board came to an end, not for a lack of purpose, but for lack of being able to keep up with technology, Mr. Lambos said. Since it was free, Mr. Lambos said it was difficult to keep abreast of all the changes that came down the road with computers. He easily could have emptied his pockets many times as the technology leapt forward.

That is also when America Online was aggressively growing and expanding. Anyone who had a postal mailbox on the Vineyard received free AOL software to go online.

In 1992, Woody Filley of Chappaquiddick started a company called CompuPlan which was intended to help people access services off-Island without having to make long-distance telephone calls.

In a February 1994 interview with the Vineyard Gazette, he said: “I know of one family that has had to restrict their son from the computer, not because of the computer service but because of those long-distance phone calls. I think it is too bad. I understand the phone company has to make a living, but this is too much.”

At the time Mr. Filley estimated there were 1,500 computers in use on the Vineyard and he thought between 10 and 20 per cent of them were networked through a modem and a phone line.

For the same story, which I wrote, Eric M. Ostrum was interviewed. The late Mr. Ostrum, then 45, was a retired college professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University. His contemporaries characterized him as one of the early founders of the Internet, for he had created a way for many computers to share information together. He lived in a second-floor apartment on Main street in Vineyard Haven and worked for the Town of Tisbury as a computer guru.

Though it was a cold winter, when I met him for the first time, his apartment was toasty and cramped with more computers than furniture. I remember how he was proud of the fact that he kept his computers running 24 hours a day and were connected to the world.

In that winter, Mr. Ostrum and others petitioned the state to hold hearings on a better way for Vineyarders to connect by telephone to the mainland without being charged long-distance fees.

Today Mr. Filley is the technology director at the high school. He has fond memories of those early years. “My first two memories are of using what was called a ‘dialog information service,’ ” he said. That service preceded dialup.

“I connected with a service in Falmouth. I had a special phone and could make unlimited calls to Falmouth. I think that was probably 1982 or 1983,” Mr. Filley said. “I had a Macintosh 128K, preceded by the Apple IIe which had 64K.

“I remember when America Online arrived on the scene. CompuServe users sneered at them,” Mr. Filley said. America Online later took over CompuServe.

“The first time I got a clue that there was an Internet was when the Internet Access Company came to the Island,” Mr. Filley said. “They had a reception at the Kelly House. It was an open house. They said, we can get you into the Internet. It was a cool thing.”

At the time, Mr. Filley worked for the Island Recycling Program, a predecessor of the Martha’s Vineyard Regional Refuse and Recovery District. He worked on computers on the side.

The Internet Access Company (TIAC), based in Bedford, offered possibly the first competitive edge for anyone seeking to save on the phone bill and get fast access to the Internet. They opened a local hub at the Merchant Mart in Vineyard Haven, with 10 incoming lines. For $19.95 a month, a subscriber could have unlimited text-only service. Their service started at 14.4 kilo-baud and soon went to 28.8 baud.

In February of 1995, they held a workshop on access to the Internet at the regional high school library.

I remember meeting Tim Jackson, the founder of TIAC. In the inaugural opening of service to the Island, he showed me around an empty office space at Merchant Mart where there were flashing light-emitting diodes on a series of metal boxes surrounded by wire looking like strands of spaghetti.

What struck me most was not his prowess in computer technology but his continuous references to a love for recreational fishing. He said a good part of his decision to open a branch on the Vineyard was tied to his love for Island fishing.

In October of 1995, Vineyard computer users got another alternative to paying long-distance phone charges. Vineyard.net, an Island company run by local enthusiasts, opened in Vineyard Haven.

Vineyard.net was formed by three forward-thinking computer users: Simson Garfinkel, a journalist, Eric Bates, a local computer geek; and Bill Bennett, an electrician.

Kathy Retmier, president of Vineyard.net, said the seed was planted by Mr. Garfinkel, a reporter who moved to the Vineyard from Boston and wanted a faster connection on the Internet.

“Eric worked at South Mountain as a carpenter and was dabbling in computers,” she said. “He also worked for the town of Oak Bluffs as their system manager. He was the Mac guy.”

Mr. Bates first moved to the Vineyard to become a deckhand aboard the topsail schooner Shenandoah. Today, at 48, he remembers that time well.

“I moved to the Island in 1983 from college, Dartmouth,” he said. “I worked for John Abrams building houses. On the side I was hacking.”

In those early years, Vineyard.net was an Internet provider. Customers saved lots of money by dialing into the Vineyard.net system rather than calling long-distance to the mainland to get an Internet connection.

Today, TIAC no longer exists. And the early technology has been superseded by cable and DSL services.

Vineyard.net still is in operation, but the company’s emphasis now is about helping customers with Web design and other Internet-related services.

One of the most striking periods in the arrival of the Internet on the Island coincides with President Bill Clinton’s decision with his wife Hillary Clinton to make the Vineyard their summer White House. While much changed here, two significant technological events happened on the Island while President Clinton was in office: digital access to the world and digital photography.

When the Clintons first came to the Island in the summer of 1993, Island journalists watched as they tried to communicate through the wires and by satellite with the rest of the world.

At the start of President Clinton’s time in office, reporters filed their stories slowly through telephones. By 2000, the last year of the Vineyard summer White House, reporters and photographers were filing their stories and photographs through the Internet.

In 1993, still photographers shot film that had to be processed before images were wired back to newsrooms across the country. Local camera stores that processed film did a booming business. By the end of the Clinton administration, almost everything, even the cameras, were digital. Huge files of digital pictures were sent back electronically.

At the time, Ed Jerome was principal of the Edgartown School. When the Clintons were vacationing on the Vineyard, the administration used the Edgartown School as the summer White House press office. Mr. Jerome said he was amazed at the technology changes that occurred in just those few years.

“At first they had runners bring back the tape to the press office,” he said. “By the end of the Presidency they could send it, the pictures, by phone.”

Mr. Filley looks back over the last 20 years as a series of “wows.” Computers became faster and more efficient and changed the way people communicated. Today every cell phone has an onboard computer and a still camera, and some have video cameras.

“In a sociological way, how does this thing in a influence our lives?” Mr. Filley asks. “What does the Internet mean for us as individuals, as a community and the future?”

When he looks to the future, he sees computers being incorporated more and more into daily appliances. “You will talk to your television. There will be artificial intelligence,” he said, concluding:

“I look at these as tools. When you glorify them, you lose out on their whole potential. They are for education and communication. When you look at a computer and see it as a mysterious box, you are missing the point.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »