Sunday marks the 67th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

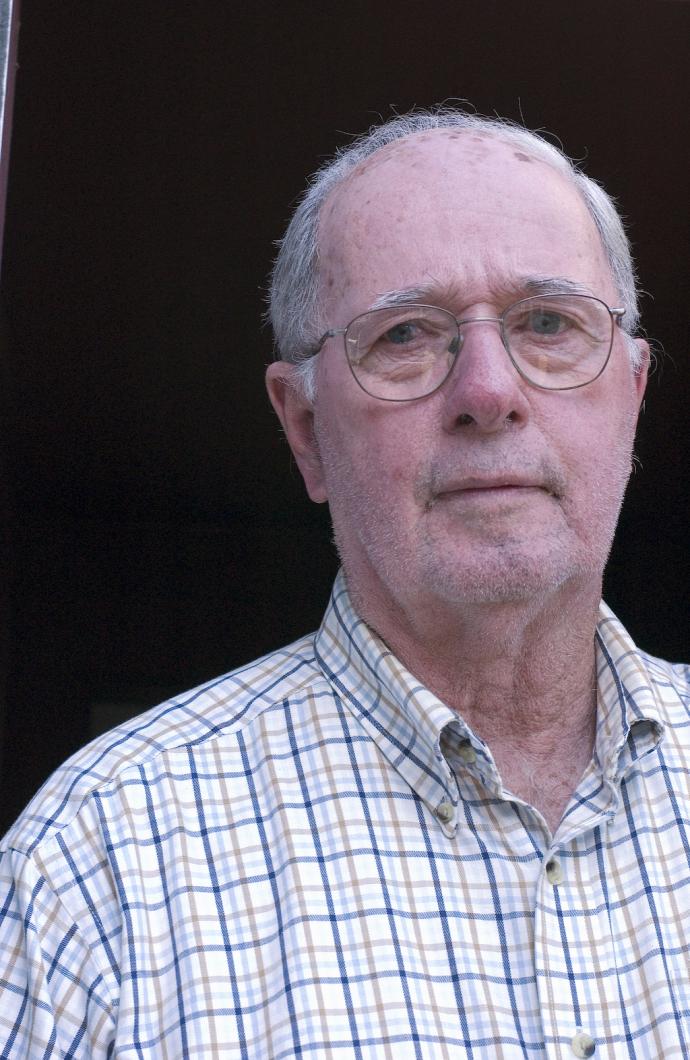

Noel C. Orcutt, 79, of Edgartown was there. He was 12 years old and he witnessed the events of Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941 up close. He saw aircraft flying overhead. He watched Pearl Harbor and the fleet ablaze at night.

He remembers going off to elementary school two days earlier on an army transport truck. He and his family lived at Schofield Barracks, a few miles away from Pearl Harbor.

“We were kids sitting in the back of an open truck,” he said. The truck made the trip to an elementary school in Honolulu every school day. He remembers seeing Pearl Harbor then as a calm port. “Driving past it, it was just like going past the beach on the way to Oak Bluffs,” he said in an interview this week. “There was a great little cove. The driver said he was going to speed up. They were burning the sugar cane fields, he said, getting ready to harvest. The sky was filled with smoke. And we drove by. No one thought a thing about it, until after Pearl Harbor happened.”

Mr. Orcutt believes now that the burning of the cane was a deliberate action by Japanese sympathizers to give pilots on Sunday morning a blackened landscape, pointing the way to the military cove, where the largest assembly of battleships in the Pacific resided.

He recalled being awakened early Sunday morning by a loud house-shaking explosion not too far away. His bedroom with his brother was on the second floor.

“I was an athlete. I jumped out of bed and I ran outside,” he said. He was still in his pajamas. “It was a hell of a bang. I ran out to the sidewalk and looked up and there is this plane going by. I said what the hell is this. I had no idea what was going on. There was fire coming out of its wings. There was a round circle on the wing. I had never seen a round circle on a wing. I had no idea. Another airplane went by. I could see fire coming out of the wing. It was a machine gun. As I looked up, I could see the pilot, only a couple hundred feet away. I could see his helmet, his goggles on. I can only see the side of his face. He is strafing. It was only for a second,” he said, continuing:

“Then I went upstairs, I yelled at my father. ‘Planes are going by! They have fire coming out of their wings,’ I told him.

“He leaped out of bed. He asked me: ‘What else?’

“I told him they had red circles on their wings. My father said: ‘We are at war.’ ”

In that instant the world changed. Mr. Orcutt, his father Col. John Wesley Orcutt, who headed up ordnance for the South Pacific, his mother Irene, his older brother John, 16, and his older sister Mazelle, 15, were all there.

“He yelled at my brother: ‘You get dressed. Get the car and you and your mother and sister get to the nearest beach. Stay there. Get there as soon as you can and stay there until they come for you. Get away from anything that is military.’ ”

Mr. Orcutt recalled they left the house thinking they’d be back. But they didn’t return for a month. All the families from the base were rounded up and moved to another location.

That night, Mr. Orcutt remembers piling into the same kind of army personnel transport truck that he had ridden every day to school. But this time the back of the truck was covered with canvas, shielded from the night and any possible attackers. Even the truck lights were shielded.

“Late at night we were evacuated from the base and taken to Honolulu. I am a 12-year-old kid. I got to be nosing around. I made sure that when I sat in the truck I was at the tailgate, sitting on the wooden bench, so I could look back,” he recalled. “I kept peeking out as we were driven. Now, as we go by Pearl Harbor again, you’ve seen the pictures with the Arizona and all those ships burning. That is what I saw. I saw the smoke going up. They were silhouetted in the night. This must have been around nine or ten o’clock at night. But you lose all sense of time.”

Mr. Orcutt remembers the uncertainty and confusion that followed the attack. In those days there was no CNN news coverage, and certainly nothing like the hour-to-hour coverage that was given to the Sept. 11 attacks or to last weekend’s terrorism attack in Mumbai, India.

“My father worried paratroopers were coming in, that they would bombard the town,” Mr. Orcutt said. “There were rumors every day. The Japs were parachuting into Honolulu. Yet there was nothing. It was all foolish,” he said.

A month later his family was allowed to return to their home at Schofield Barracks. When they got there, Mr. Orcutt remembers his mother. “When she opened the refrigerator door, I thought my mother was going to die. Everything inside was rotten. I remember trying to help my mother wash out the refrigerator.”

After that the Orcutt family moved to San Francisco and then to New Bedford, while his father stayed behind. Mr. Orcutt seldom saw his father during the war.

His older brother John served in the Army during the Normandy invasion and was awarded a bronze star and two purple hearts.

Mr. Orcutt joined the Air Force at the age of 22, after college, during the Korean War. He worked as a radar mechanic in Mississippi and in Europe.

He is reluctant to talk about his Pearl Harbor memories, preferring to defer to others who served in the war.

His father retired after 34 years in the military. Mr. Orcutt, who turns 80 this month, has no mementos from the seven months he lived in Hawaii, just his memories. He said he has never wanted to go back.

He has lived on the Vineyard for 42 years; he came here because he married an Islander, Bernice Wells, on Independence Day in 1951.

They moved to the Island in 1965 when he took a position as director of the Martha’s Vineyard Youth Center. He did the job for two years, and then worked as a carpenter, at the Martha’s Vineyard Airport and at the Martha’s Vineyard Shipyard. Mrs. Orcutt worked at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital as a nurse. They raised four sons.

He said he prefers to look past the Pearl Harbor experience where over 2,000 people were killed and another 1,000 injured, and a nation went to war.

“You look up and you see them firing away. It is done. It is over. I made it. Let us move on,” he said.

Comments

Comment policy »