Everyone loves a redemption story, but there is reason to believe Americans love them more than most other people.

One of the several notable ways that Americans are significantly different from people in other advanced countries, international polling has shown, is that they are far more likely to believe that individuals themselves, not the broader forces in society, determine their success in life.

Succeed or fail — it’s down to your personal mettle. It’s part and parcel of American individualism.

Thus this nation’s strong attachment to redemption stories. If one cannot blame anyone else for one’s failings, then one had better believe it is possible to redeem oneself, and then get busy doing it.

As Nat King Cole sang: “Will you remember the famous men who had to fall to rise again/ So take a deep breath, pick yourself up, dust yourself off and start all over again.”

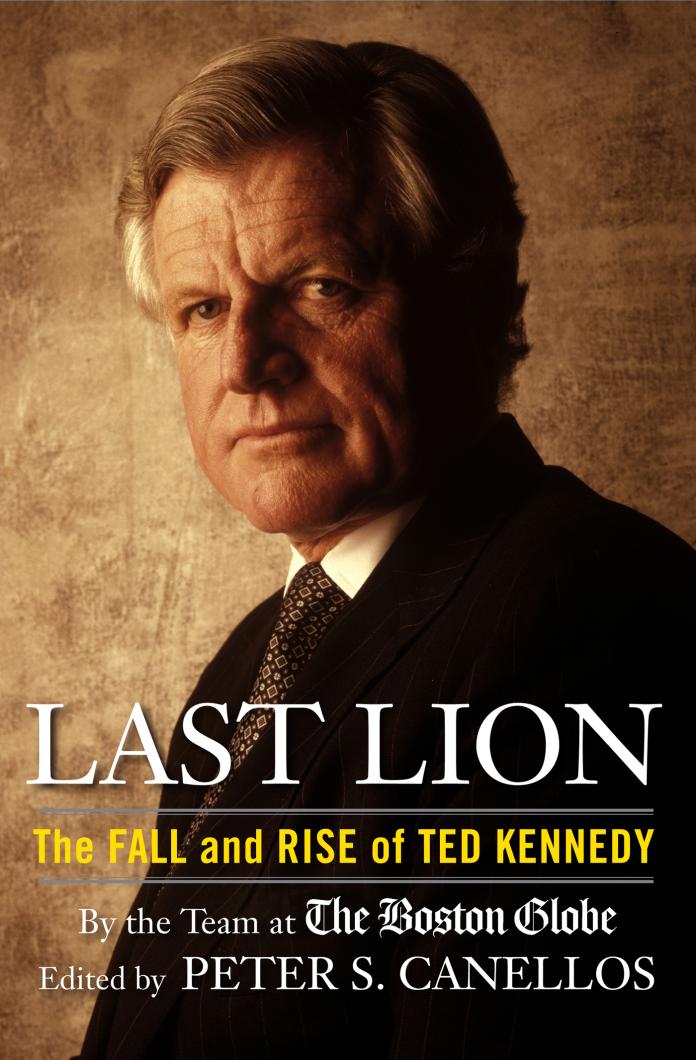

Yes, Americans love a redemption story, which probably explains why Last Lion, a biography of Edward M. Kennedy, written by the political team of the Boston Globe and edited by Peter Canellos, is subtitled “The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy.”

And what a great redemption story it is.

Now, anyone with even a passing knowledge of political history knows from what Ted Kennedy had to be redeemed — his actions on this Island, almost exactly 40 years ago. A car he was driving crashed off the Dike Bridge, on Chappaquiddick, and a young woman died.

And anyone with even a middling knowledge of political history also knows how he redeemed himself in the public domain, becoming the master negotiator of the U.S. Senate and a powerful force for liberal causes.

But the book does not start with an account of either of those things. It starts by painting a picture of what it was to grow into a life where everything — wealth, ambition, flaws, tragedy – is absurdly exaggerated.

The pressure was there literally from Ted Kennedy’s birth, on Feb. 22, 1932, the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birth.

“The proud father, who already had dreams of a Kennedy becoming the first Catholic president, often pointed out the felicitous date to others,” says the book.

“As parents, Joe and Rose had defined their jobs much like partners in a franchise. Their product: national leaders who would vastly expand the Kennedy name.”

Joe Kennedy, patriarch of what would become America’s most famous family, believed strongly in that American myth of self-determination. His maxims included: “no losers in this family” and “no rich idle bums.”

“They were an extraordinary duo,” said Mr. Canellos. “Joe Kennedy is this sort of Great Gatsby figure, embodying the American dream, but in all of its ruthless excesses. And Rose was a very strict, discipline-oriented mother.”

Pity the child who is a vehicle for family ambition. Pity the child who seems less able than his siblings to fulfill that ambition. And pity even more the child who finds that family expectation ever more concentrated as time and siblings pass.

That was young Ted’s lot.

He started out as the “tag-along kid” behind his three accomplished brothers, the light relief in a serious family, a mix of born-to-lead superiority and youngest child inferiority.

And no doubt about it, he was problematic at times.

He was kicked out of church for misbehavior as an altar boy; in trouble at school for borrowing the car of a former police commissioner and family friend, then abandoning it when it would not start; was kicked out of Harvard for two years after getting a friend to sit a Spanish exam for him.

His father’s comment: “Don’t do this cheating thing, you’re not clever enough.”

That reflected the general assessment: that while Ted was in some ways the most attractive of the boys politically, the best looking, the best speaker, the most gregarious, he was not as smart, and was lacking in judgment.

But he also was the sweetest-natured of them and a “cheerful source of positive energy” as Mr. Canellos put it, through the family’s tribulations, “but at some cost to his own development.”

“One thing which surprised me,” said Mr. Canellos, talking about the researching and writing of Ted Kennedy’s life story, “was how lonely his childhood was.”

He’d been to 10 different schools by age 11. His parents were continually at him about his marks, spelling, and his weight.

“And he was exposed to tragedy from a young age,” said Mr. Canellos. “He was 12 when his brother Joe died, early teens when his sister Kathleen died, and his brother Jack was almost killed in the war.”

Just the year before he drove off the bridge on Chappaquiddick, his last brother, Robert had been assassinated. No doubt Ted showed bad judgment in the incident, but the pressures in the man’s life — and a diagnosed concussion — must mitigate somewhat.

And then, of course, there is the succeeding 40 years of atonement. We won’t go into those here, save to mention his enduring commitment to sweeping health reform. Suffice to say he emerged as one of the most effective legislators, and most well-regarded individuals in the Senate.

Obviously, the writing of Last Lion was spurred by the fact of Senator Kennedy’s sudden and recent infirmity. On Saturday, May 17, 2008, he fell ill at his Hyannis home and was later diagnosed with a brain tumor.

But the real impetus, said Mr. Canellos, was less the fact of the illness than the general reaction to it.

“All of a sudden . . . in what we were hearing from our readers, the questions that came back to us, there was a sense of people focusing on the full arc of Kennedy’s life,” he said.

“People were seeing it as a real progression, as somebody who was born into a very pressured circumstance, who at age 36 had the expectations of tens of millions of people foisted on him, who committed an act at Chappaquidick that forever raised questions about him, who disappointed his supporters by not becoming President, and then built this monumental career in the Senate.”

From the start, Mr. Canellos envisioned the book as “a story of failure and redemption.”

But, given Senator Kennedy’s parlous state, it had to be written quickly. Seven members of the Globe political staff wrote it between them.

“I was the story editor and drew up the basic outline for the book, came up with the division of labor and edited it,” Mr. Canellos said.

“I wrote the introduction and epilogue. I also provided some of the connective tissue among the different sections.”

“We were able to put the book together in seven or eight months by having so many people working on it,” he said.

It is a testament to the writing or Mr. Canellos’ editing, or both, that there is great continuity of style throughout, and not much duplication (although the assertions of Ted Kennedy’s devotion to family become a bit repetitive).

“It was a great Globe-wide project that was able to draw the expertise of not only the seven writers who are listed, but also on the memories of Globe retirees and other resources of the paper like photographers,” Mr. Canellos said.

He concedes Last Lion is a friendly biography. Not an authorized one, or a hagiography, though.

And despite the quick turnaround, said Mr. Canellos: “We think it is definitive.”

Of course, the Ted Kennedy story is not over yet. He lived to help Barack Obama, with his promise of health care reform, to the presidency — health being Kennedy’s most cherished policy interest.

It would be fitting if he were able to live long enough to see major changes to health care in this country. Sadly, with all the ideology, the horse-trading between vested interests and the consequent delays, it looks increasingly as if the change will not happen in his lifetime.

Still, he will go out redeemed in the eyes of most.

The cause of comprehensive health care reform may well be irredeemable.

Comments

Comment policy »