The Cape Cod Canal was still an idea. And it would be years before the advent of navigational tools that are taken for granted today such as radar and global positioning systems. Mariners could only communicate with each other and the shore by sight and sound, and they established their location in the huge expanse of ocean with the aid of a sextant, clock and compass if the sky was clear.

In that context, tomorrow marks the 100th anniversary of the day a ship broke apart in a raging sea on the unforgiving Wasque shoals. And while the Vineyard has seen many shipwrecks through the centuries, the wreck of the Mertie B. Crowley endures as one of the most thrilling tales of heroism at sea. Miraculously, no lives were lost on that Sunday, Jan. 23, 1910.

And the main hero in the story was a bow-legged, steely-eyed Edgartown seaman named Levi Jackson, who did what the Coast Guard and other would-be rescuers could not. With a small crew of four, Captain Jackson steered his 32-foot fishing sloop Priscilla through treacherous swells to rescue Capt. William Haskell, his wife and 13 crewmen who had lashed themselves to the rigging of the rapidly sinking 296-foot six-masted schooner. The family names of the five heroes on board the Priscilla that day are still well known on the Island: Jackson, Kelly, Doucette and Benefit. The men were later awarded a Carnegie bronze medal.

But that’s getting to the end of the story. First, the beginning.

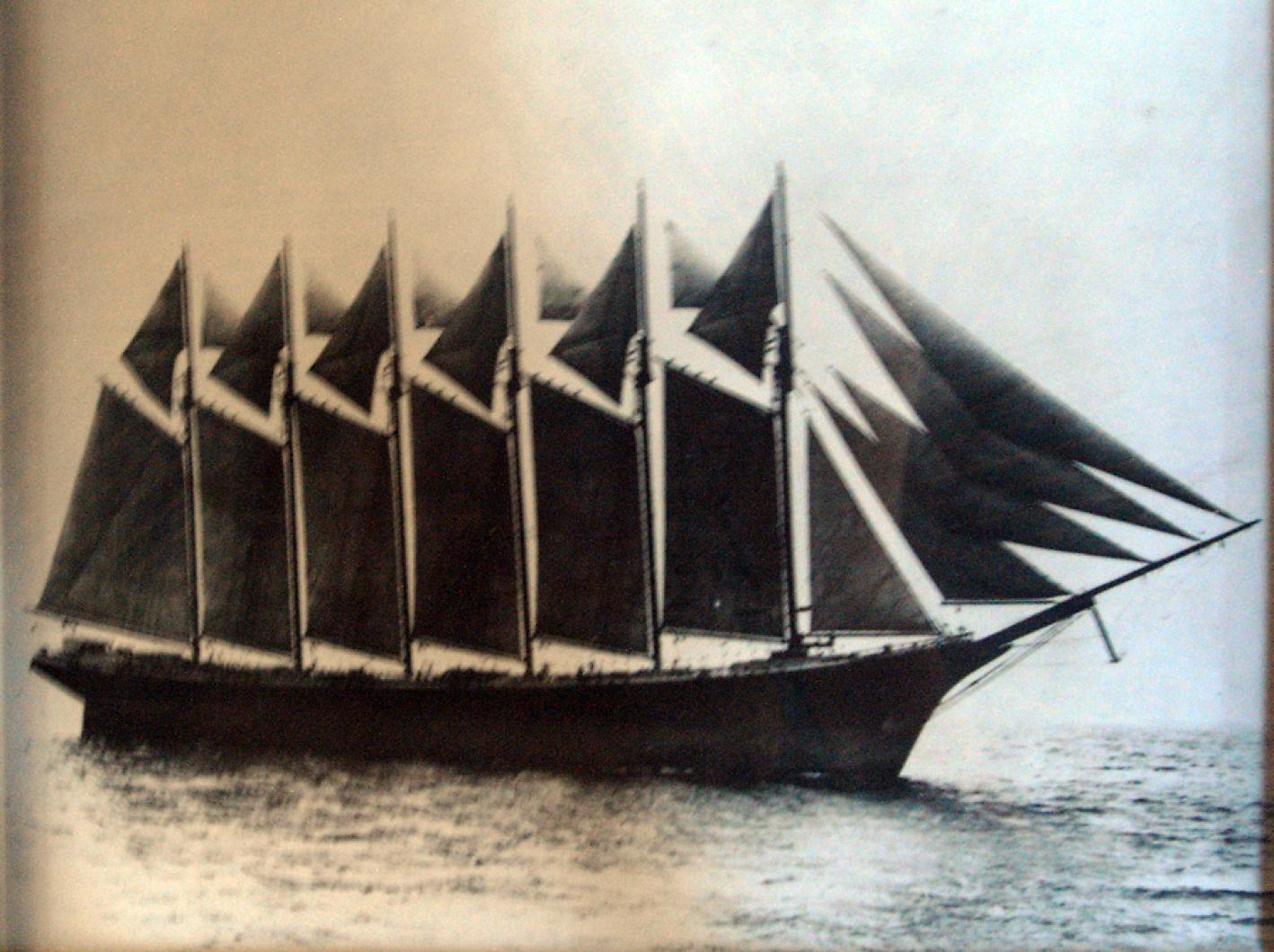

The Mertie B. Crowley left Newport News, Va. on Tuesday, Jan. 18, loaded with coal and headed for Boston. She was considered one of the best schooners of her design, owned by the Coastwise Transportation Company, built and launched in Rockland, Me., just three years earlier. She had no propeller, though she had a steam engine available to raise and lower sail.

Captain Haskell, 47, was accompanied by his wife, Ida. There were two mates, an engineer and 11 other sailors. At some point the ship lost her bearings; according to reports, when they spotted a fixed beacon in the fog and rain which they believed to be Shinnecock on Long Island, it was in fact the Block Island Light. At 5:35 a.m. that Sunday, the ship went hard aground on the Wasque shoals. Too far from shore for an easy rescue from the landside, crew members went aloft in the foremast and lashed themselves to the rigging to stay alive.

Word of the grounding traveled quickly, and at 9 a.m. two boats left Edgartown harbor; one was the 32-foot Priscilla, a fishing sloop powered by motor and sail and captained by Levi Jackson and his crew of Patrick and Henry Kelly, who were brothers, Louis Doucette and Eugene Benefit. The second was Viking, captained by John Slater. Another captain, John R. Forman, was on board the Viking.

A third vessel, the Coast Guard cutter Acushnet, captained by Abram Osborn Jr., also approached. Neither the Acushnet nor the Viking were able to help without putting themselves in danger.

By 10 a.m., the Mertie B. Crowley had broken in half and her stern had sunk. Only the forward section of the vessel and masts and rigging were visible above the angry seas off Chappaquiddick.

And only the Priscilla had a shallow enough draft to reach the lee side of the rapidly sinking schooner. At great risk, Captain Jackson’s fishermen were dispatched in dories to go alongside the wreck and pick up the crew.

There are many different accounts of the rescue.

On the 50th anniversary of the grounding, a story in the Gazette recalled: “The great seas sweeping over the Crowley and the crew in the rigging made a picture which nerved the gallant rescuers to supreme efforts of daring. Jackson tried repeatedly to push his power smack Priscilla through the great breakers. But combined sails and steam could not do it until early afternoon. Then, the tide having changed and the sea not running quite so high, he succeeded in putting her safely through the breakers, lowered her sail, and with her engine at its top notch of speed succeeded in placing the staunch 32-foot craft a short distance to leeward of the wreck, then he anchored.”

At one point Patrick Kelly was tossed into the sea when his fishing dory overturned. Waves tossed him into the ship’s rigging. Holding tight to the rigging with one hand, his other hand was on the ship’s cook.

The book Shipwrecks of Martha’s Vineyard, written by Dorothy R. Scoville and published by the Dukes County Historical Society more than 30 years ago, carries the following account: “Captain and Mrs. Haskell were taken to the home of Thomas J. Walker, Edgartown physician, who gave the survivors medical attention. The next day the captain entered the Marine Hospital in Vineyard Haven, for treatment of shock and exhaustion. Frank Beetle and John Prada took the two mates into their homes while the seamen were cared for at the Edgartown Fishermen’s Association rooms on Main street.”

Two years after the rescue, the five-member crew of the Priscilla each received a bronze Carnegie medal and cash awards totaling over $6,000.

Today relics from the Mertie B. Crowley are scattered about the Island and beyond. The Martha’s Vineyard Museum has the medal that was given to Patrick S. Kelly. The museum also has the original 46-star American flag, a huge stars and stripes that flew aloft and was recovered when the vessel was salvaged, a gift of the Kelly family. The museum also possesses the ship’s house flag. The white letters on the flag are MBC against a blue and red background. The flag was donated to the museum by the Edgartown Yacht Club through S. Bailey Norton Jr.

A large piece of timber, believed to have come from the ship, sits on the porch at the Chappaquiddick Community Center.

The original 25.7-foot yawl that the Mertie B. Crowley carried was restored and resides at Mystic Seaport, donated to the museum by Robert S. Douglas. Mystic also has the quarter board from the stern and the masthead pennant.

The Kelly family has paintings, including one oil painting of the sinking ship that was done by William Alexander Black, an Edgartown artist and sign painter. A more precise and detailed painting by Chandler Moore was commissioned in 1955 by Cameron MacLeod; it hangs in the home of Andrew Kelly.

And there are of course the descendants of the heroes themselves, including the Kellys, Benefits and Jacksons. Among them are Paul C. Jackson and his wife Mary. Paul is the grandson of Levi Jackson, and his considerable collection of historic memorabilia and artifacts includes a neatly organized binder that contains all the newspaper clippings and other accounts of the rescue at sea. “He was always a lucky person,” Mr. Jackson said of his grandfather. “He spent his whole life on the water. He was five feet tall and weighed 120 pounds. He always wore an oil coat and boots. The ocean didn’t bother him. His nickname was Rye-De-Di-Die,” he said, a colloquial shortand for “ready to die,” because he survived so many dangers at sea.

Other descendants include Michele Whitney of Edgartown, who is the granddaughter of Louis A. Doucette.

Andrew Kelly of Edgartown, grandson of Henry, said his grandfather and granduncle Patrick were originally from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Had they not known Levi Jackson, the rescue would have not occurred. He said the rescue changed their lives, and had they not participated, the two might have returned to Nova Scotia. Instead they stayed. Henry Kelly took the money he was awarded and built their home on the corner of Simpson’s Lane and Pease’s Point Way.

Andrew Kelly believes there is a generational connection in his father Richard’s deep interest in the Edgartown fire department; it has to do with those who risk their lives for others, he said.

The Martha’s Vineyard Museum will host a centennial observance of the grounding and rescue this coming June.

And while artifacts and scrapbooks preserve history in their way, it is the tale of the Mertie B. Crowley that endures through its telling, again and again.

In its 50th anniversary recollection the Gazette wrote:

“The story of the saving of the lives of Capt. William H. Haskell, his wife and crew of thirteen is one of the most thrilling tales in the history of sea heroism along the section of the Atlantic coast. Because it is remarkable, that no one was lost, no one injured, and there was little suffering, it is probable the story will not attract the attention that usually accompanies a tale of heroism at sea, but for all that it is a most touching story of the way in which five brave men went out for battle with the seas, and seven hours later returned with one woman and fourteen men all taken out of the rigging of a vessel pounding to pieces on the reef on the south side of the Island.”

Comments (11)

Comments

Comment policy »