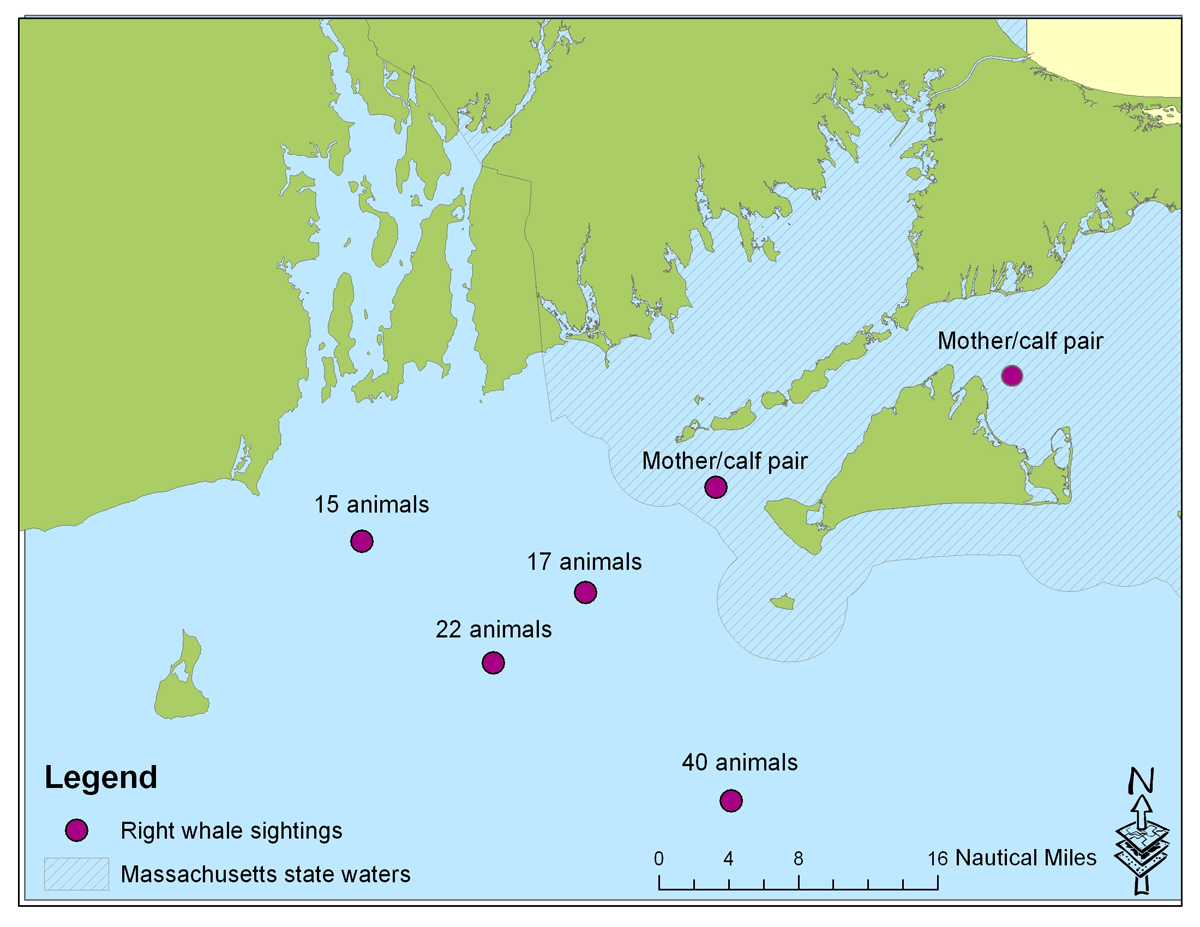

An extraordinary group of right whales — some 95 living specimens of the rarest of all large whale species — was feeding in the waters between Martha’s Vineyard and Block Island this week, while two mother and calf right whale pairs were spotted even closer to the Island.

On Saturday, federal scientists in the air saw one mother and calf pair just a mile or two off Oak Bluffs harbor, and on Tuesday, a distinct pair was spotted in Vineyard Sound.

All boaters are urged to keep to speeds of 10 knots an hour or less; the whales are not always visible from the surface, and a collision with even small boats at speed can kill a whale and wreck the boat. State and federal law also prohibits any vessel from approaching within 500 yards of a right whale.

The Steamship Authority is running extra lookouts on its ferries between Hyannis and Nantucket after right whales were spotted south of that island, general manager Wayne Lamson said yesterday, but the other sightings have not affected its services to the Vineyard.

Most whale deaths now are caused by collisions with ships or entanglement in fishing lines. Scientists believe there are not more than 450 North Atlantic right whales in the world — so almost a quarter of the known population is near the Island.

“It’s pretty darned unusual,” said an excited Erin Burke, protected species biologist at the state Division of Marine Fisheries, of the whales between the Vineyard and Block Island. Right whales are more common in Cape Cod Bay, a designated critical habitat.

“This is the first calf for both moms seen off Martha’s Vineyard,” according to Ms. Burke. “Mom and calves often show up in ‘strange’ places. Some people believe this is because moms are giving the calves a ‘tour’ of potential good places to eat . . . Right now, most of the right whales we would expect to see would be in either Cape Cod Bay or Great South Channel.”

There were no National Marine Fisheries Service flights on Wednesday, and yesterday their sighting planes were not headed for the Vineyard-Block Island area.

“But they [the whales] are just west of the Vineyard, and they are going to have to come east,” Ms. Burke said in an interview Wednesday.

Charles (Stormy) Mayo, senior scientist at the Center for Coastal Studies, reacted cautiously at first to the report of so many of these rare marine mammals gathered southwest of the Vineyard. “That would be among the largest aggregation of right whales in one area, ever,” he said. “If it’s even a third that many, it’s a great story. It’s worth reporting if you had any mother-calf sighting, or if you had 10 or more in one place. But 95 is excessive,” he said.

When he saw yesterday the state map noting the aerial sightings, his response was “Wow!

“They are referring to a regional concentration, but still that is a remarkable concentration of an exceedingly rare creature.” He continued:

“My guess is these animals have found a rich source of food. And you would normally anticipate seeing these aggregations form for days, a week, maybe even weeks.”

Think of right whales as grazers, Mr. Mayo said. “A concentration of right whales is usually associated with good fodder,” he said, adding: “They may be doing other things . . . orgiastic kinds of socialization.”

“It is probably a feeding aggregation,” agreed Division of Marine Fisheries deputy director Dan McKiernan, suggesting there must be plankton or copepods in the area.

An average adult right whale consumes about a ton of food a day, eating billions of tiny crustaceans called copepods that are packed with protein and calorie-rich oils, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Mr. McKiernan called the concentration of right whales “not unheard of but not typical,” adding that in the late 1990s dozens were seen together off Rhode Island and that was considered extraordinary. He said the gathering could be brief, as such a large group might exhaust the food.

“It is unknown how much food exists in the area or how long the animals will stay there,” reads an advisory to mariners issued yesterday by the state Division of Marine Fisheries. “However, mariners around Martha’s Vineyard are advised to be on the lookout for the mother-calf pairs. Their near-surface feeding and traveling activities put them at risk for vessel collision. For the safety of both mariners and the whales, vessel operators are strongly urged to reduce speed (less than 10 knots), post lookouts, and proceed with caution to avoid colliding with this highly endangered whale.”

Mr. McKiernan noted that mother-calf pairs often inexplicably will meander into out-of-the-way places; they have been sighted in Cape Cod Canal and Salem harbor, he said. “Mother-calf pairs can and do go anywhere,” he said, and so it is critically important for vessels to be on the lookout and for commercial fishermen not to set gear in the area.

Though it is impractical to ask fishermen to remove gear in place, they are prohibited from starting fishing operations (setting or hauling gear) within 500 yards of a right whale.

Mr. Mayo too stressed the need for boaters to be cautious, noting that a research vessel going too fast in Stellwagen Bay last year had accidentally struck an unseen right whale while looking for the creatures.

Ms. Burke said studies indicated that whales could probably survive a collision with a ship going 10 knots or less, but even small boats were a danger at speed.

The National Marine Fisheries Service also issued a voluntary speed restriction for large vessels in the waters around Block Island. A separate restriction applies around Nantucket.

A general restriction applies from January to May in waters further off the coast. But any sighting of a right whale triggers the imposition of a voluntary 10-knot speed limit on ships more than 65 feet long, operating within a so-called “dynamic management area” with a 36-mile radius, for 15 days from the time of the sighting.

When the rules were being enacted in 2008, the Gazette reported that saving just two females a year could help this species on the brink of extinction, but saving more could put the North Atlantic right whale population on the road to recovery.

These are among the rarest of marine mammals; they are named because they were considered the “right whale” to hunt in whaling days. They swim slowly and float when dead.

A female right whale is expected to give birth to only one live calf every five years, usually during winter along the Florida or Georgia coast. Right whale calving season officially ended Thursday, and Florida biologists reported 19 calves were born. Last year the number was 39, the highest since counting began in 1994.

Mr. McKiernan said, “The good news is that since I began my career in conservation, under threats of lawsuits, the population was about 300. Now it is generally accepted to be 450, so it bodes well for the population.”

Right whales are born tail first, and weigh nearly a ton at birth. They generally nurse from their mother for 10 to 12 months, often swimming on her back. State educational resources note that a mother right whale may even roll over and hold her calf in her flippers.

Grown North Atlantic right whales can weigh up to 70 tons, and the adults range in length from 45 to 55 feet.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »