The federal government has given its blessing to the development of Cape Wind, America’s first big offshore wind farm, on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound.

The Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, announced his decision to approve the project, with only minor changes, at a joint press conference with Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick in the state house in Boston at noon on Wednesday. In words suggesting a conclusion to the nine-year controversy, Secretary Salazar called his approval “the final decision of the United States of America.”

In reality, however, his decision shifts the focus of the conflict from the state and federal bureaucracy to the courts.

A long list of groups opposed to the development — which would see 130 turbines, each some 440 feet tall, installed on the shoal — immediately promised legal challenges.

A release from the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound said lawsuits would be filed by seven groups against the federal Fish and Wildlife Service and Minerals Management Service for alleged violations of the Endangered Species Act.

It said the Alliance, along with the Dukes County and Martha’s Vineyard Fishermen’s Association, also would file a lawsuit against the federal Minerals Management Service for claimed violations under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, and that the town of Barnstable has filed a notice of intent to file a lawsuit on the same grounds.

“Additional legal issues include violation of the National Environmental Policy Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Rivers and Harbors Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act,” the Alliance said.

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), which claims the development will interfere with cultural practices and could desecrate evidence of ancient Indian habitation when Horseshoe Shoal was dry land, also weighed in quickly against the decision.

“We are disheartened and disappointed with Secretary Salazar’s decision,” a tribe press release said, adding:

“The tribe has no choice but to explore all of its options for relief from this decision, including injunctive relief.”

And the federal process is not quite complete, either. The project still awaits approval from the Federal Aviation Administration. Currently Cape Wind’s turbines are a presumed hazard to aviation. A spokeswoman for the FAA yesterday said it was not certain when that process would be finished, but it was hoped it would be done soon.

Regardless of these remaining hurdles, however, the federal and state governments and the developer Cape Wind Associates hope to begin construction within a year and have the wind farm fully operational by the end of 2012.

“We are very confident that we’ll be able to uphold the decision against legal challenges . . .” Mr. Salazar said.

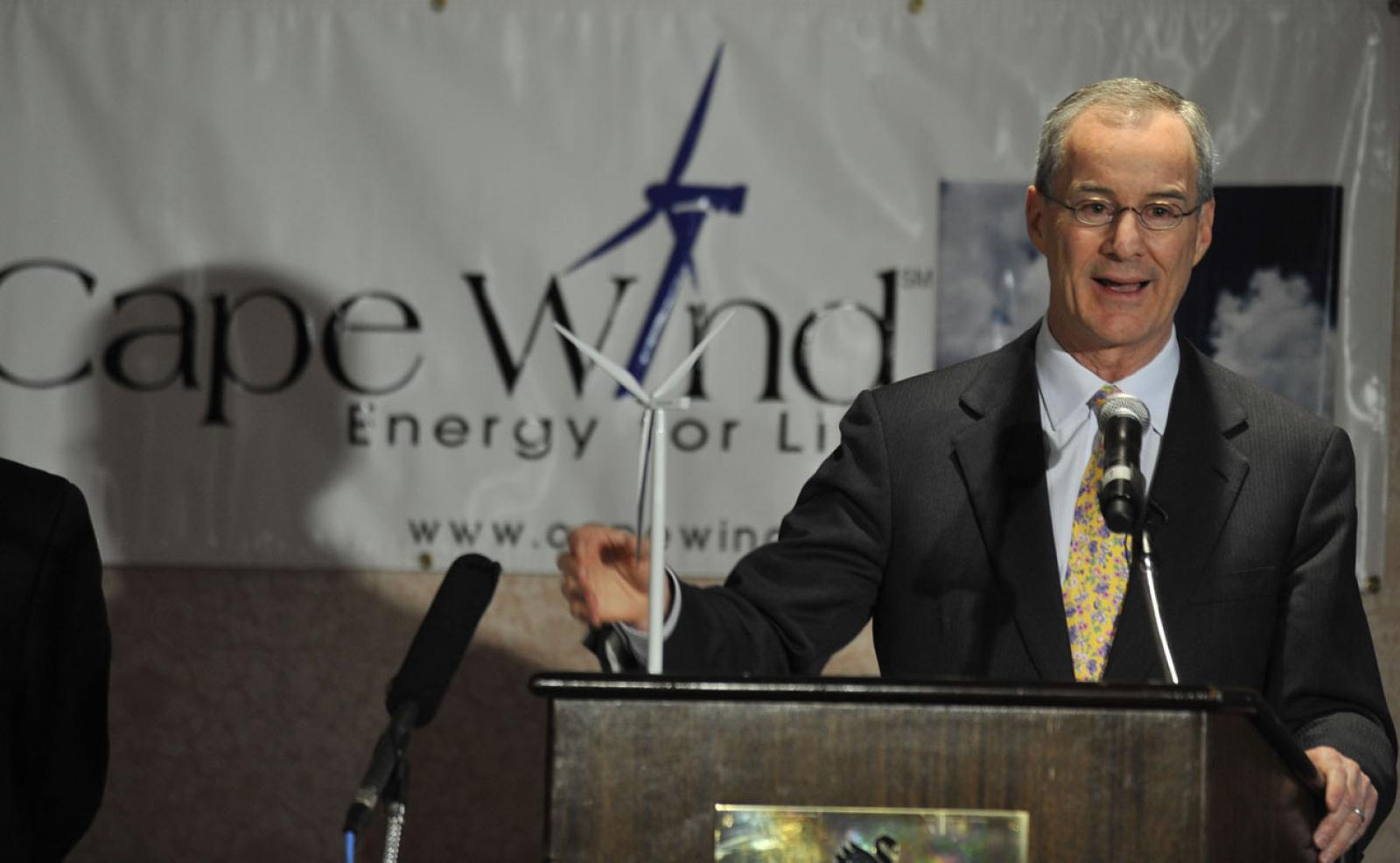

And the president of Cape Wind, Jim Gordon, was similarly optimistic. The development had been before courts or regulatory forums about a dozen times, he said, and had won each time.

In his announcement, Secretary Salazar was bullish about the benefits of Cape Wind to this region, the state and nation.

The wind farm would generate as much power as a medium-sized coal fired power plant, he said, but save the emission of some 700,000 tons of carbon dioxide each year. It is expected to bring about 1,000 construction jobs.

He hoped Cape Wind would be the first of many such projects, up and down the East Coast. Governor Patrick noted that America was 20 years behind Europe in developing offshore wind, and China also was pulling ahead.

“America needs offshore wind power. With this project Massachusetts will lead the nation,” Mr. Patrick said.

Secretary Salazar, who paid a personal visit to the Cape and Vineyard in early February to tour Horseshoe Shoal, said the decision had been a hard one, and he acknowledged many people would be unhappy with it. He specifically addressed a couple of concerns, including those of one of his department’s own advisory council on historic preservation, which recommended against approval.

“There are those who would say that any wind turbine in Nantucket Sound compromises the areas cultural and historic heritage. That was in large measure the conclusion of the [ACHP],” he said.

But history had long been written on the landscape here and would continue to be.

“Nantucket Sound has long been a working landscape,” he said, referencing its heavy use for fishing, boating and as an artery of commerce, and its existing array of bridges, communications towers and cables.

He cited a recent letter from the governors of six eastern seaboard states, expressing their concern that if he followed the ACHP advice and scuppered the wind farm it would set a precedent making it almost impossible to site offshore wind projects anywhere along eastern seaboard.

He also addressed the critics of the long approval process, saying government had to establish a “more rational and orderly” way to do it.

“Cape Wind has been under review for nine years. There has been multiple layers of review upon layers of review, countless meetings, bureaucracy, uncertainty on all sides, conflict,” he said, adding:

“There is no reason why an offshore wind permit should take a decade to review and approve.”

Secretary Salazar emphasized changes to the original plan for Cape Wind which would mitigate its impact. The number of turbines had been reduced from 170 to 130 and the wind farm layout been re-oriented (this concession was made some five years ago, long before he became involved), and would be painted off-white to make them less visible, and lighting of the structures had been minimized.

The approval also came with the caveat that there be further archeological work at the site. A “chance finds” clause in the lease requires the developer to halt operations and notify the Department of the Interior if anything significant is found.

In his press conference after the decision was announced, Mr. Gordon emphasized the opportunities for employment which would be generated by the project, not just during construction, but long-term in its operation and in spin-off business for other renewable energy industries.

“Siemens [a turbine manufacturer] is going to be opening up their North American offshore wind office in Boston,” he said.

Mr. Gordon said it was time the project’s opponents accepted the decision, stopped adding cost through legal action and “joined the nation” in embracing alternative energy.

But Audra Parker, the president and CEO of the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, countered by saying “the fight is not over.”

Apart from the effects of the development on Nantucket Sound, she questioned the economics of the project, saying that more than nine years into the process, there still was no comment from Cape Wind on how much its power would cost consumers.

Cape Wind is currently in negotiation to sell its electricity to National Grid.

“It will be an above-market contract that will increase people’s electric bills,” Ms. Parker predicted, citing a recent National Grid deal for wind power done in Rhode Island, which she claimed set rates three times higher than standard.

“It’s a shame Secretary Salazar, Governor Patrick, Cape Wind, won’t talk about it,” she said.

Mr. Gordon did not respond directly to questions about pricing, beyond pointing out that the prices for fossil fuels are volatile and trending sharply up into the future, and do not reflect certain costs, to health, to the environment, and to America’s military spending in protecting overseas sources.

Ms. Parker claimed the decision was a political fix.

Certainly the politics around Cape Wind are complex. Prominent Democrats, notably the Kennedy family whose Hyannis Port estate would have views of the proposed wind farm, are opposed. But the Obama and Patrick administrations are strong supporters. The Massachusetts Republican party opposes it, but Republican governor of Rhode Island Donald Carcieri lauds it.

And the proposal has also split environmentalists, between those whose focus is on protecting the local environment and those more concerned about the global picture.

The resulting delays and battles in getting approval, though, and the prospect of further delays in the courts apparently have not diminished Mr. Gordon’s determination.

It took 86 years for the Red Sox to win a world series championship, he said; by comparison, the almost 10 years delay on Cape Wind was “the blink of an eye.”

He said his company also was looking to future involvement in other offshore wind projects.

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »