In August the reeds just beyond the open door to the Mugwump shed sway and hiss in a warm breeze off the lagoon. Inside the building, the shape of the hull that the skeletal framing only hinted at a month before begins to reveal itself, plank by plank, as the crew sheathes it from keel to deck.

“I love putting on the first two or three planks,” says Ross, who comes to Mugwump with business for Nat. “There’s nothing more rewarding than watching the shapes develop as you’re twisting and bending them on there.”

For Ross, it has been a busy summer at the main yard, too. He and the crew have just launched the second in a class of twenty-one-foot sloops for one Vineyard client and are now working on an eleven-foot tender for another. He looks up at the sweep of Rebecca’s hull. Todd McGee and Casson Kennedy lift a plank, and Ted Okie and Mark Laplume clamp the ends to the sawn frames. “But by the time you’ve put the twentieth plank on,” he adds, “you can’t wait to see the end of it. It’s the same with every part of boatbuilding because so much of it is repetitive.”

Nat slowly pushes a plank into the mouth of a planer. David stands on the other side, ready to catch it. The goal, through many runs, is to shave each plank down to one-and-seven-eighths inch. As the timber trembles its way through the machine, the wail is tremendous. To either side, the shavings — mauve from the angelique planks fastened high along the sheer line and low along the keel, and off-white from the silver balli planks in between — have been gathered into two gerbil-nest piles, both waist high.

Silver balli, another wood selectively harvested in Suriname, is rich in oil like teak but much less expensive. Oil reduces the amount of water that can seep into the grain, lowering the risk of rot. The builders want each plank to be as long as possible to minimize the number of joints (called butts), which can move and leak. But because planks twist as they run along the hull, there can be no defects — no sapwood, no worms, nothing that can fracture or decay over time. To make sure the schooner project has enough planking, Nat has ordered twice as much silver balli as the builders would need if all of it had been perfect. What’s left over will be trimmed to rid it of problems and used in the bulkheads.

Each plank curves in a unique way as it runs along the framing, and the outboard face of each sawn frame has been individually and precisely beveled so the planks lie fair — smoothly, without humps or flat sections — against them. The top of each plank is also beveled to fit snugly against the right-angled bottom of the plank above. And each joint is reinforced on the inside with a butt block where the planks meet end to end. No plank is more complex than the garboard, a weighty single timber of angelique that lies just above the keel. The garboard widens markedly at the stern to cover the added girth in the low, aftermost sections of the boat.

The outside of the planks is still rough when fastened to the frames; the inside faces of the planks have been backed out (or cut) to match the curve of the frames.

With the job complete at the end of September, the builders begin to plane and sand the outside face of the frames by hand, the silver balli lightening with each run over the grain. Especially hard to reach is the area amidships, below the waterline. Todd, Casson, Ted, and Mark duct tape thick pads of packing foam around their knees and kneel on staging planks. Their spines twist left and right, and their necks arc backward under the gentle, spreading belly of the schooner, as they plane and sand the planks over their heads.

At the end of the day, Todd’s head and shoulders are shrouded in shavings. He wears a mask to keep the dust out of his throat and lungs. His face is mummified with silver balli powder and sweat. He steps from under the hull, rolls his shoulders, bends at the waist, stretches his back, and looks around for a different plane. It’s inside the hull, so he must climb the staging and go over the rail to find it.

“It’s harder to get in and out now,” he says, looking along the length of the hull. Rebecca is all planked up.

Like the main yard across the street, Mugwump has begun to attract visitors who have heard about a historic schooner being built on Martha’s Vineyard and want to see how it’s done. Parents bring young children, who stand shyly at the shed door until invited in for a closer look. Nat or David stop work to discuss the dimensions of the hull, the weight of the lead in the keel, the places the schooner will go, the sort of wood they’re using — and why they’re using wood to begin with.

“They’ve earned a lot of good will,” says Whit Hanschka, a blacksmith in Tisbury, of Gannon and Benjamin, where he worked through most of the 1990s. “You see it in the range of their customers. Everyone from the seriously rich people who have them build new boats, to the fishermen, to the random house-carpenter types who need something funky. Nat and Ross will always drop everything and spend a half-hour talking about whether to use teak or mahogany on some project, where the guy doesn’t know the difference between spruce and fir. Who knows, maybe that’s why they’re not rich men at this point. But people like them. If you do that for ten or fifteen years, then people begin to realize that you’re genuine.”

To the extent that anyone has ever considered this help a favor, it was repaid in full after the night of Tuesday, Oct. 17, 1989, when, for reasons unknown, the main yard burned. Fed by lumber, shavings, linseed oil, and the hulls of several boats, the inferno left the building looking like a meteorite had hit it.

Vineyarders appeared with offers of help at dawn the next day. They gave the builders tools their grandfathers had used. They placed orders for boats and sails, paying in advance. They lent office space, donated sewing machines, held benefit dinners and a concert that included James Taylor and his talented siblings. On the morning of Saturday, Nov. 11, a shed-raising was scheduled. Nat thought two dozen people might show up. He arrived at eight o’clock to find at least thirty master carpenters and hundreds of regular folk ready to build. That morning the framing lay on the ground. Two days later they were shingling the roof.

“I remember Ross was quoted in the paper as saying he never realized they were a successful boatyard until they burned down,” says his nephew, Antonio Salguero. “I think that fire instilled in them a stronger sense of their place in the community, instead of being just some business on the waterfront, make or break, season by season. They were always stronger than that — they had a following at that point. But I think it clarified in their own minds that they had a clientele that was as strong as friends.”

“I think cotton is very much underappreciated in a wooden boat like this,” says David as caulking begins in October. At the moment, light slits through the seams up and down the hull and all along it; now comes the time to seal it up tight.

It’s clear David enjoys this part of boatbuilding, working with mallet, cotton, and flat steel tools of varying widths called caulking irons. “People don’t understand what the function of cotton is. It’s not just to keep water out. A hull like this with no cotton in it would be just limber as can be. Get all that cotton in there and you’ve put tons of pressure between each seam. It turns the thing into one rigid structure. It acts like a truss. You can actually hear the difference while you’re caulking the vessel. When you’re starting off, it’s kind of a hollow sound, and by the time you’re all done, the boat is almost ringing like a bell because it’s so tight.”

Frank Rapoza, who learned caulking during his boyhood at the Concordia Boatyard in South Dartmouth, leads the crew. As they have for weeks now, the men begin the day by taking sandpaper to the planks. They sand away fuzzy places on the edges where the cotton might catch. They use reefing hooks to dig out grit between the seams.

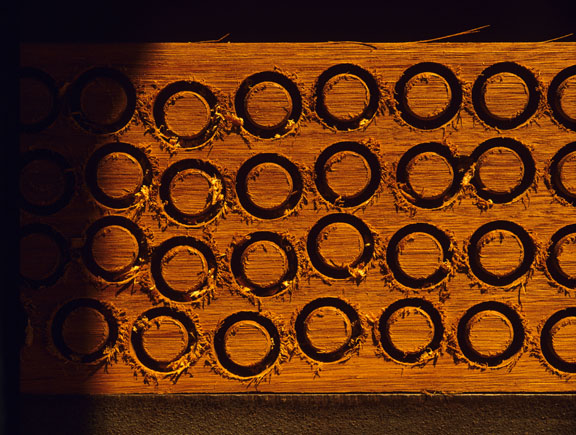

For all the seams but the lowest five, the boatbuilders insert two strands of cotton into the seams. Using two types of caulking irons, these strands are looped into loose coils and driven (the caulker’s word is tucked) into the seams. The number of tucks varies according to the width of the seam — the wider the seam, the more closely spaced the tucks. David guesses that by the time the crew is done, Rebecca will have two hundred pounds of cotton set into the seams of her hull.

The bottom five seams are first filled with a strand of cotton and one or two strands of oakum, which is made up of tarred, coarse hemp fibers. Oakum resists the degrading effects of diesel fuel, which can seep into the seams if it spills into the bilge from the fuel tanks. The caulked seams are then painted with a coat or two of red lead (a primer and preservative), and then puttied to seal the job up tight. Above the waterline, the hull is given its first coat of white paint — like red lead, a primer to keep the wood from drying out while the rest of the hull is built.

These first coats of color foreshadow the livery that the schooner will wear on her launching day — a brilliant white hull set off sharply by a bottom of royal red. Meanwhile, another milestone comes on the October evening when a mallet and caulking iron strike a last ringing blow against the schooner’s hull:

Now Rebecca can float.

Comments

Comment policy »