James Joyce once declared that if Dublin were ever destroyed, it could be wholly reconstructed from the text of his famously impenetrable opus, Ulysses. On Wednesday night, or Bloomsday night rather, the Dublin of Joyce was thus faithfully restored in Vineyard Haven.

Bloomsday, for the uninitiated, is June 16, the day the fictional Leopold Bloom embarked on his debauched exploits throughout Dublin, as recounted in Ulysses. Drawing on excerpts from Joyce’s works and musical standards of the time, the Arts & Society players commemorated the occasion at the Katharine Cornell Theatre with what they claim is the oldest continuous public celebration of the life and works of the author. The production was at turns silly, caustic, nostalgic and melancholy, fittingly capturing Joyce in his many moods.

It is also now marked by sadness, following the news over the weekend that David O’Docherty died while swimming in Katama Bay on Saturday. On Wednesday night Mr. O’Docherty, a Dubliner by birth and renowned artist and musician, played tin whistle at the outset of the evening, as he has done for many years. This account was largely written before that tragic event occurred.

Bloomsday included a recitation by George Ricci of Gas from a Burner, a little known poetic broadside an aggrieved Joyce penned about a printer who refused to publish The Dubliners on decency grounds. The poem, which takes the form of a monologue by the printer himself, Ricci delivered with the conviction of a vulgar, self-important man.

“Ladies and gents,” he began, “you are here assembled/To hear why earth and heaven trembled/Because of the black and sinister arts/Of an Irish writer in foreign parts.” It was an appropriate introduction to the man whose work so intimidated the Irish public but nonetheless served as its most unsparing and affecting chronicler.

Following Mr. Ricci’s printer on stage was Joyce himself, who cut an imposing figure in his trademark white suit, fedora and adhesive mustache.

“Last night I took a walk from Tisbury to Oak Bluffs,” he informed the crowd, “and I was forced to walk across the most stupid, completely inadequate excuse for a bridge. Somebody even told me that they spent millions of dollars constructing it. Well, you might learn from this story that you could have built a finer bridge and for a lot cheaper too.”

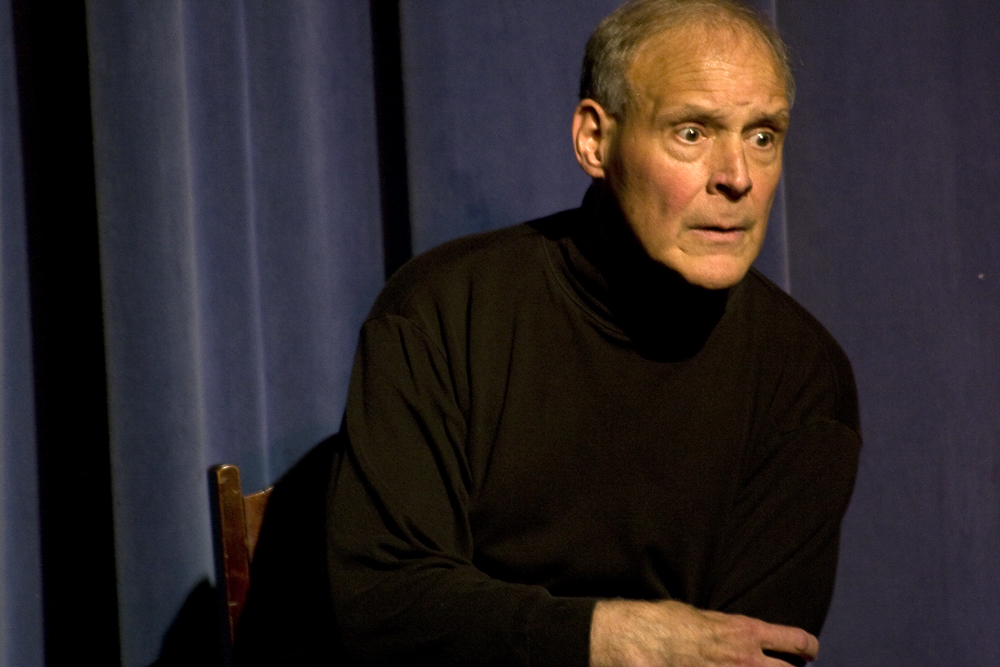

Joyce (looking rather like Vineyard Haven doctor Gerry Yukevich) then retold the tale of the Cat and the Devil, an obscure children’s story he wrote for his grandson in which the devil (played convincingly by Buck Reidy complete with business suit and French accent) builds a bridge for the town of Beaugency on condition that the first to cross it give up their soul (a cat crosses it).

Following the trajectory of Joyce’s career and mirroring one of his favorite literary techniques, the evening explored more mature work as it drew on.

Reciting the entirety of The Boarding House, a cynical short story of upward social mobility from Joyce’s The Dubliners, Mr. Yukevich gave a performance that felt less like a monologue than a yarn spun over a few pints by an exceptionally gifted storyteller.

The virtuoso acting was punctuated at each interval with songs of Joyce’s turn-of-the-century Ireland, that heady time of cultural ascendancy, burgeoning nationalism and ongoing strife with its imperial neighbor.

“Come you back to Mandalay you British soldier,” boomed Buck Reidy with full-throated Victorian jingoism during one interlude. Katrina Nevin sang softly and sweetly of the cockles and mussels of Molly Malone, turning some Irish eyes in attendance misty.

The showstopper however was Natalie Rose. On the page, Joyce’s disorienting stream-of-consciousness technique can tax the patience of even the most experienced reader. On stage, however, in the gifted hands of one utterly attuned to its rhythms and eccentricities, the effect is sympathetic, in which the audience shares in even the most intimate details of the narrator’s mental life. Ms. Rose’s portrayal of Molly Bloom in the extended rambling soliloquy that closes Ulysses was wistful, candid and completely human.

Joyce’s recurrent themes of lost love and faithfulness were here felt most deeply. Even a film star like Bill Paxton — who was in the audience — must have felt some humility at the performance.

On Wednesday night the theatre was outwardly little changed apart from a Guinness is Good for You sign adorning the stage, but Joyce would have recognized his own Dublin here on the Vineyard, an Island surrounded by the snotgreen sea.

Comments

Comment policy »