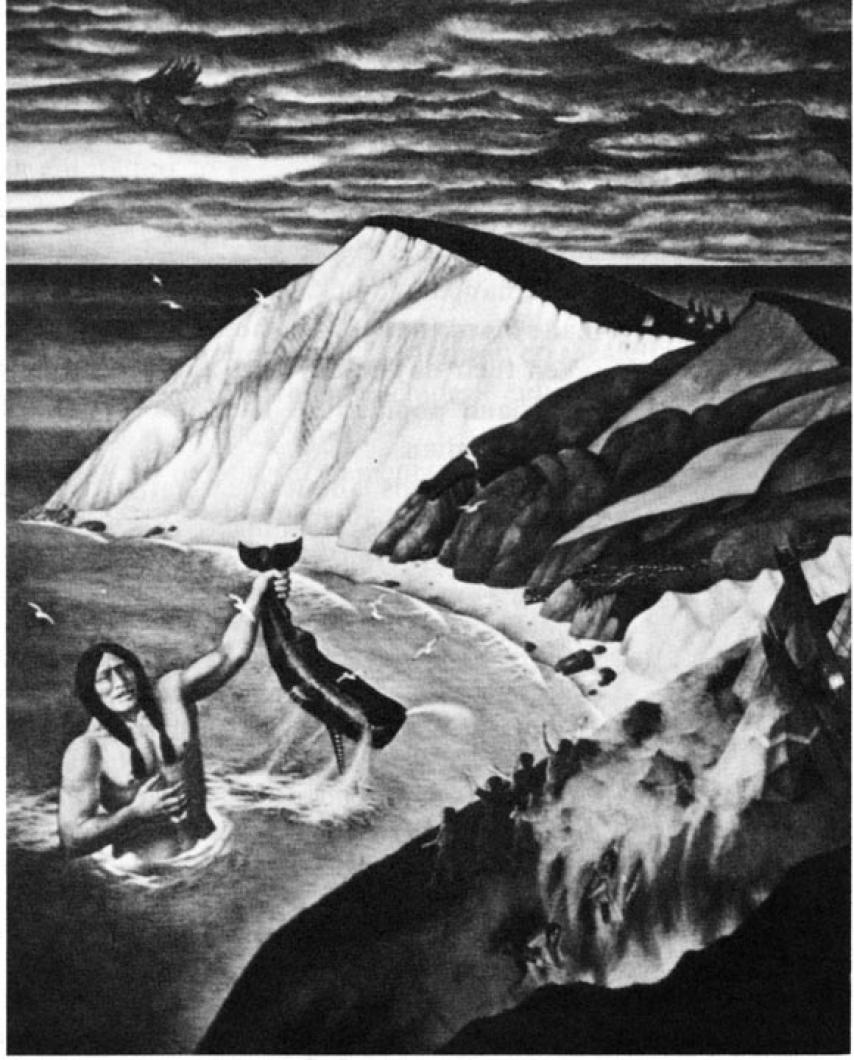

Once there was a giant named Moshup who created the Island of Martha’s Vineyard to escape violent war and fighting on the mainland. Isolated on the tiny bit of land surrounded by sea, he one day became homesick, and set out to build a bridge back to the mainland. He waded out into the Vineyard Sound and threw down a trail of giant boulders to step across. But in the middle of his effort, Moshup was bitten on the toe by a crab, and returned home to nurse his wounds. He never resumed his project, and his bridge remains unfinished. The boulders, which form a sort of sea trail between Aquinnah and Cuttyhunk, are now known as Devil’s Bridge.

Or so one version of the story goes.

On Wednesday night, Islanders gathered on folding chairs set up in a tiny room of the Vanderhoop Homestead, home of the Aquinnah Cultural Center, to watch a film that addressed the legends of Moshup from an unusual perspective — that of an outsider.

Seasonal Aquinnah resident Rose Kennedy Schlossberg is not a member of the Wampanoag Tribe that credits Moshup with the creation of their landscape. But growing up, she and her siblings were affected by the stories just the same.

“I was always interested in the mythology surrounding the creation of this area, which is very particular to the tribe,” said Ms. Schlossberg, introducing her documentary short film The Legends of Moshup.

As a child, she attended the annual pageants at which the tribal people acted out those legends. Then in her senior year at Harvard University, when Ms. Schlossberg took a personal documentary film class, she opted to explore her connection to the legends of her neighbors as part of a class project.

“The reason why I wanted to make this video was because I had been fascinated by the legends of the tribe and the heroes in this place,” she said. “I wanted to document that in a certain way, and it ended up being filtered through my family’s experience and my own childhood coming here.”

The film became not only an exploration of the tribal legends’ effect on her own family, but a testament to the oral history that has kept the stories circulating among the Wampanoag people for hundreds of years.

The film was narrated by tribal member Adriana Ignacio, who shared a handful of Moshup’s mythic experiences and explained why legends like that of Devil’s Bridge have taken hold among the Wampanoag people for centuries. Other speakers included Ms. Schlossberg’s brother, Jack, and sister, Tatiana. who explored their own reactions to the legends. Jack, for instance, remembers being scared sleepless for nearly four years as a child after hearing stories of a Wampanoag antihero and Moshup nemesis who liked to cut out the eyelids of women so their eyes were left forever open. Later, a tribal member said that legends of Cheepee were as effective as a wooden spoon in discouraging bad behavior in her and her siblings as youngsters.

But Ms. Schlossberg didn’t claim consistency in her own family’s versions of the legends.

“Our interpretations, or memories of them would be a little bit distorted,” she said, adding that the stories aren’t necessarily meant to be consistent. Instead, they become a product of each individual’s perspective and experience.

They also serve different people in different ways.

“Different stories are used for different purposes,” said tribal member Tobias Vanderhoop in a discussion following the film screening.

“There’s the creation story of our home, but then . . . there are stories told for the purpose of helping people understand; if you’re connected to the Wampanoag community, then there’s an expectation of how you should act. Or an expectation of what you should do in your role as a man or a woman. And it would be different people who would tell these stories. So the stories may not always come out exactly the same,” he said.

But that’s the beauty of oral history, Mr. Vanderhoop said.

“I am very staunch about not having our stories written down and put into books,” he said. “Our oral tradition is a living tradition.”

Set the words to paper, and you suddenly invite conflict over whose version of events is accurate, he added.

The landscape played a large role in the legends of Moshup and in the film. In scenes wedged between interviews and narrated clips, Ms. Schlossberg captured the quiet beauty of Aquinnah. A crystal clear Witch Pond; wind blowing through the tall grasses lining a footpath through a remote field; a view of the ocean from the top of the Gay Head Lighthouse. Or the fog coming up over cliffs and sandy dunes, which Ms. Ignacio said was believed to be smoke from Moshup’s tobacco pipe. “We believe that that is Moshup, still in our presence today,” she said in the film.

Ms. Schlossberg said that the screening at the Vanderhoop Homestead will likely be the extent of her small film’s distribution. It’s available to watch online, but she said she has no plans to take it any further. But perhaps this is a first step in a filmmaking career; after graduating from Harvard in the spring, she now has plans to move to New York and work in the film industry on documentary films.

Though the film was meant to tell the story of Ms. Schlossberg’s own experiences, along with those of her family, she never turned the camera on herself. She said that while she didn’t appear onscreen, she was in the film in many ways. Her voice came through, asking questions, and, as she put it, “prodding for the right answers.”

The style she chose for the final cut was, she said, the most effective way to tell the story she hoped to tell. She explained it as keeping a part of herself invisible, but still present.

“Hearing [the stories] coming from my brother and my sister actually became a lot more interesting to me, and made it feel much more personal,” she said.

Comments

Comment policy »