On Tuesday morning West Tisbury School science teacher Karl Nelson told his eighth grade class the outcome of the lab experiment they were about to begin related directly to their everyday lives, something they couldn’t survive without.

Puzzled looks crossed with curiosity around the room.

Today the students would learn how combustion relates to respiration.

Mr. Nelson, whose class ranked number one in science scores in the state on the MCAS exam this year, runs labs four days a week, a rigorous schedule for eighth grade science.

Nevertheless, he takes no credit for the achievement.

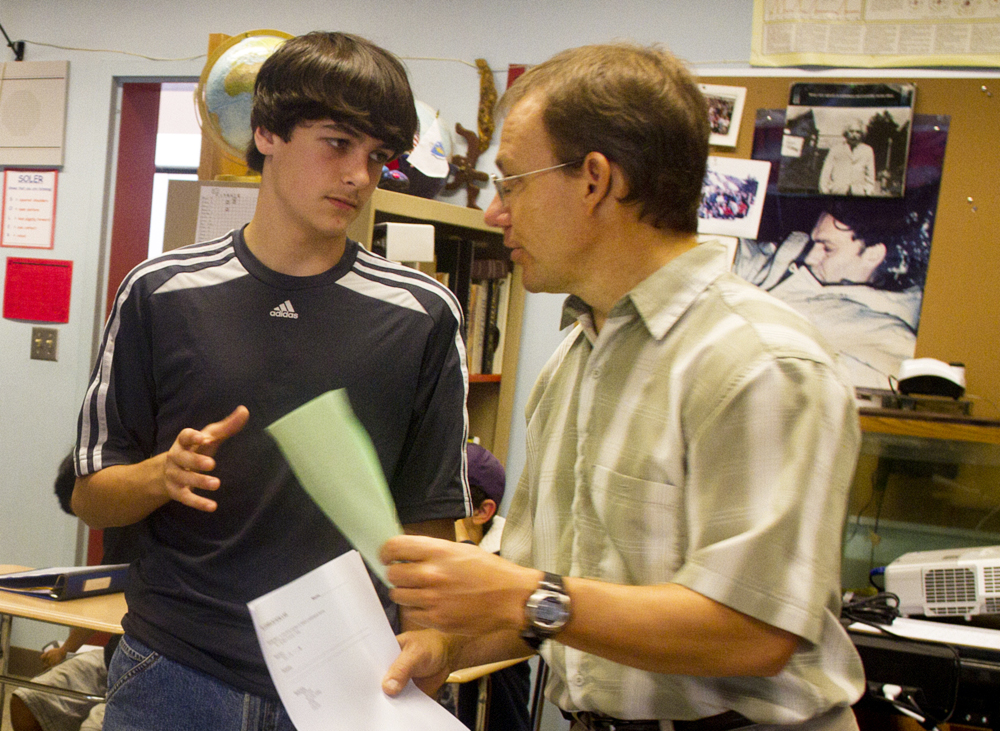

“All the credit goes to the kids, they respond to what I do and they work hard,” he said between classes on Tuesday. “If that weren’t the case, it doesn’t matter how good a teacher you are . . . The kids work hard and the parents are supportive so that’s a huge part of the equation.”

Mr. Nelson’s students have done consistently well on the MCAS test in recent years, usually ranking in the top 10 out of 500. Last year they ranked second in the state.

“One of the keys to my teaching is being myself with the kids and treating them like they’re one of my own,” Mr. Nelson said, adding: “I really keep things moving in the class and make things interesting. Fun is a tricky word because they work hard . . . none of them would say it was necessarily fun — but they don’t mind being in my class and working hard.

“We do a lot of activities, a lot of labs, a lot of hands-on activities, and a lot of discussion.”

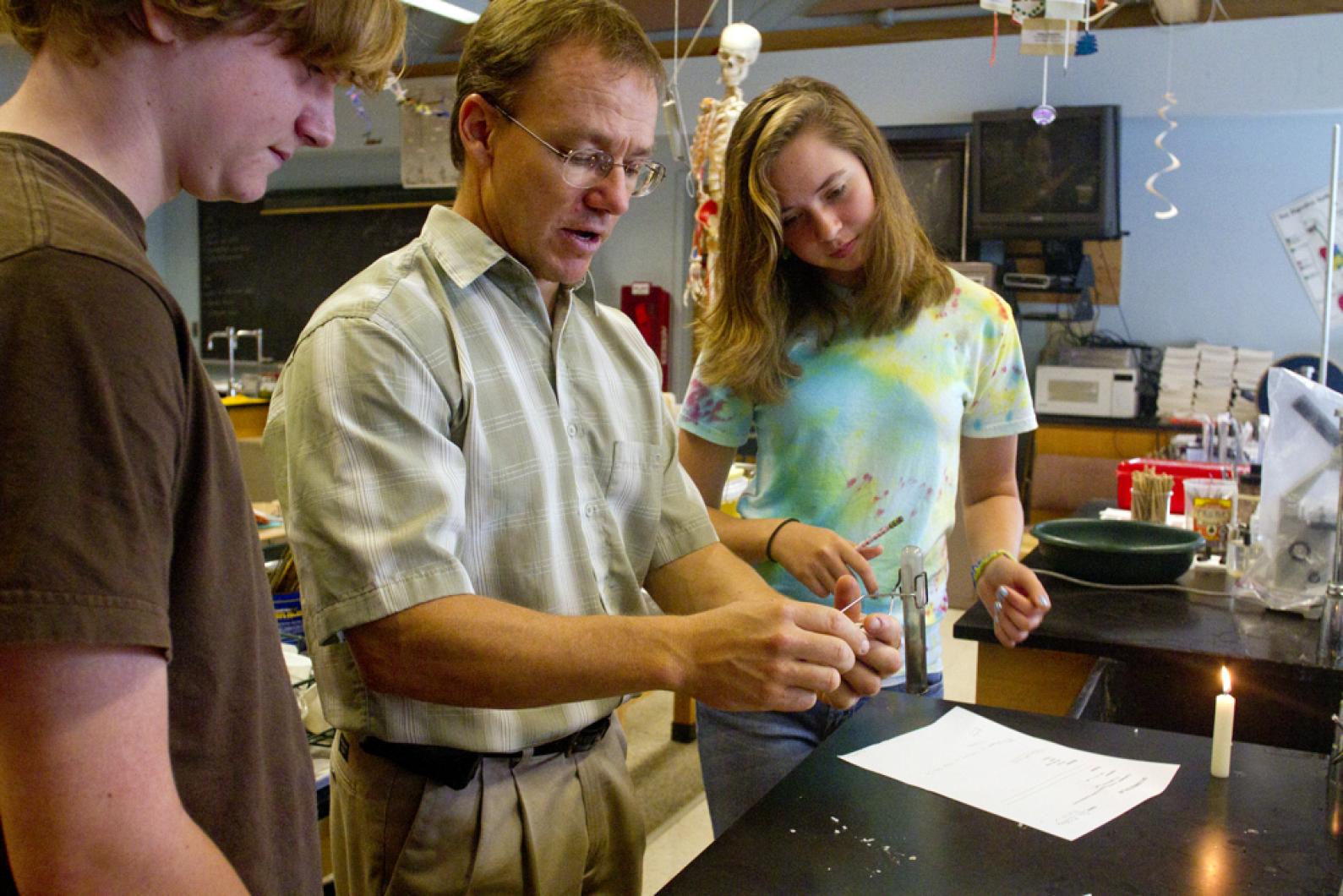

For lab on Tuesday, students were paired up by Mr. Nelson, and after a brief bit of junior high moaning at the fact they could not choose their own partners, the students went right to work. Mr. Nelson instructed them to make observations before and after they held a glass test tube over a flame. “What is one change you witnessed in the test tube?” he asked.

“There’s a black substance,” one student said. “Is it solid, liquid or gas?” Mr. Nelson prodded. “I think it’s gas,” replied the student. “Touch it. Rub that gas with your finger,” he said. The class burst into laughter.

“I entertain the kids, and they like that,” Mr. Nelson said. “If you can sell them to yourself first and foremost, they’re far more likely to glean what you’re talking about and what you’re trying to impart to them. If you can make connections between things so they have anchors and make connections to the real world and do it with humor and a smile and who you are — than that’s huge in my opinion.”

He said doing a lot of lab work keeps the students moving within the classroom and out of their chairs. “You sell yourself and the information and there is an art to that. I don’t claim to be perfect at it, but it works for me and what I do,” he said. “Largely the kids here work hard, and they want to work hard for you if you show them you care.”

His classroom is strict and traditional; he does not tolerate calling out, he makes sure to call on students who haven’t spoken and he encourages everyone to dig deeper.

But he said that doesn’t mean he “teaches to the test,” a common criticism among educators about MCAS.

“The test is based on state standards,” Mr. Nelson said. “I prepare the kids. I teach to the standards, I teach what the state tells me to teach. And frankly the curriculum, the standards they have are good standards . . . that’s what I do and that’s what I do excellently.”

He said he doesn’t begin to look at MCAS review problems until a month and a half before the spring test, and even then he only takes one day a week to look at problems with his students, sending them home with a few practice problems.

“When they take the test, if they do poorly it shouldn’t be a function of not knowing how to approach the test. Then it wouldn’t be a test of what they know or understand,” he explained. “Teaching to the test would be a mistake. You won’t prepare them well, they won’t be ready. They have to have the freedom to learn and explore, and you have to be able to make connections that anchor in their head.”

He continued:

“The key is to make connections in kids’ heads so that when they are assessed on tests like the MCAS they understand the information,” Mr. Nelson said. “You don’t know what the questions are going to be like when the test comes. It’s a fool’s error to teach to the test . . . it’s a recipe for failure.”

In the Tuesday lab, students completed the equation for combustion and respiration on the chalkboard, and the moment came when it all clicked: Respiration is the transport of oxygen from outside air cells within tissues, and the transport of carbon dioxide in reverse, just like the combustion lab they had just completed.

Mr. Nelson said if he could change anything, it would be to link different subjects more seamlessly. “Now as it is, 80 per cent [of what I teach] I can tie them together so the kids can see the forest through the trees, not just the individual tree trunks,” he said.

Before class was dismissed, he held a review for a cell quiz the students had the next day. “I’ll be around during lunch and recess if you need help,” Mr. Nelson said. “Ciao!”

Comments

Comment policy »