Wind farms have long provoked a certain cognitive dissonance among environmentalists, who favor renewable energy but oppose the negative impacts of turbines, including bird strikes and habitat displacement. The effects of turbines on bird populations are fairly well understood after a decade of European experience but less is known about their impact underwater, especially on local species of whales and sea turtles. Last Thursday at the Oak Bluffs Public Library, University of Rhode Island ornithologist Peter Paton and Sarah Smith of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council addressed the concerns during a presentation of research underway in anticipation of wind turbine development in the waters between Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

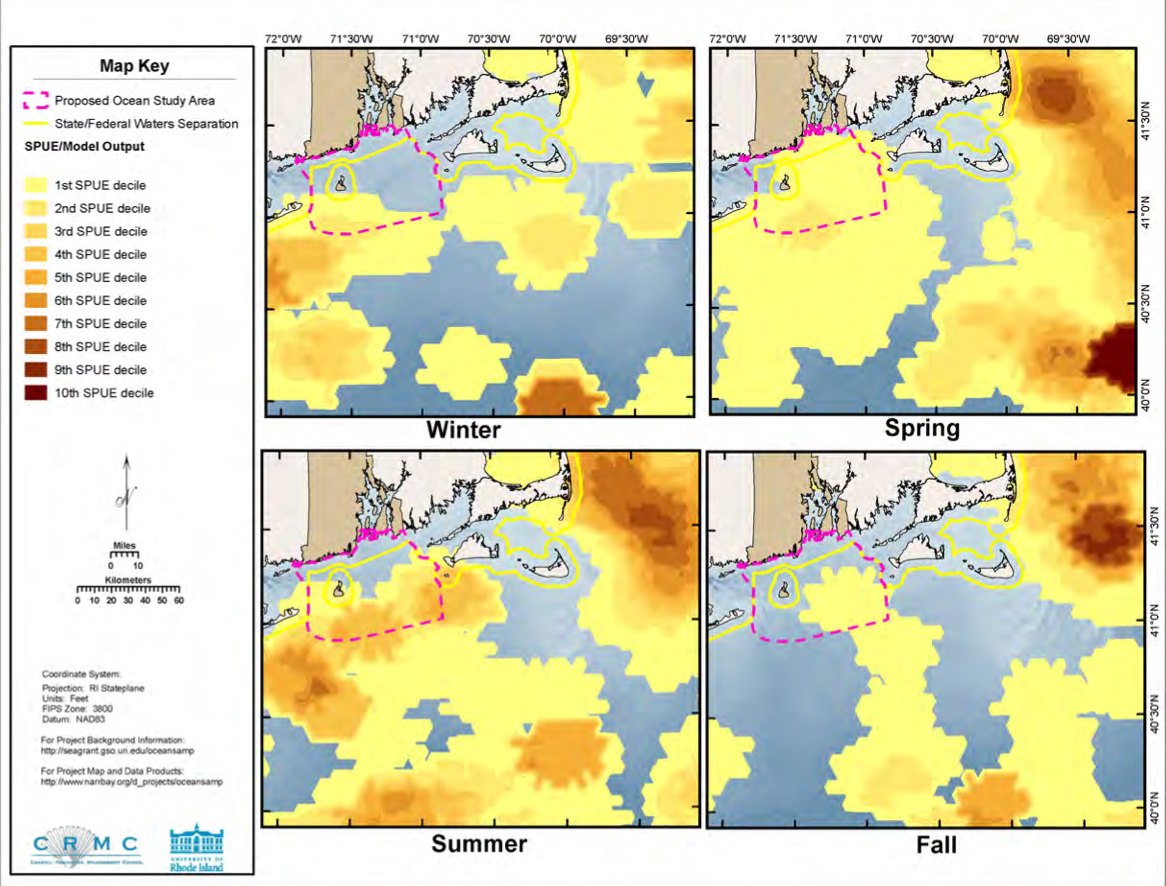

Their work is part of a $7 million effort on the part of Rhode Island known as the Ocean Special Area Management Plan. Funded by a variety of state and federal sources, the management plan aims to comprehensively survey the 1,467-square-mile area from Montauk to Noman’s Land. Rhode Island has opened the area up for potential wind energy projects, and Massachusetts has agreed to jointly develop areas in its northeast corner. Determining the best sites with the least impact on local fauna was the subject of Thursday’s talk.

Wind turbines’ reputation as the “lethal Cuisinarts in the sky,” as Mr. Paton put it, can be traced back to the construction in the 1970s of the Altamont Wind Pass in California, which he called “the world’s worst idea” in terms of turbine placement. Sited in the middle of a migratory habitat for raptors lured to the area by abundant California ground squirrels, the turbines, many of which are currently being disassembled and replaced at a cost of over $1 billion, kill 4,000 birds annually, many of them protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Every year over 100 golden eagles, 300 American kestrels, 300 red-tailed hawks and nearly 400 burrowing owls are killed by the swinging blades. Unsurprisingly the prospect of expanded wind development has drawn concern among bird experts.

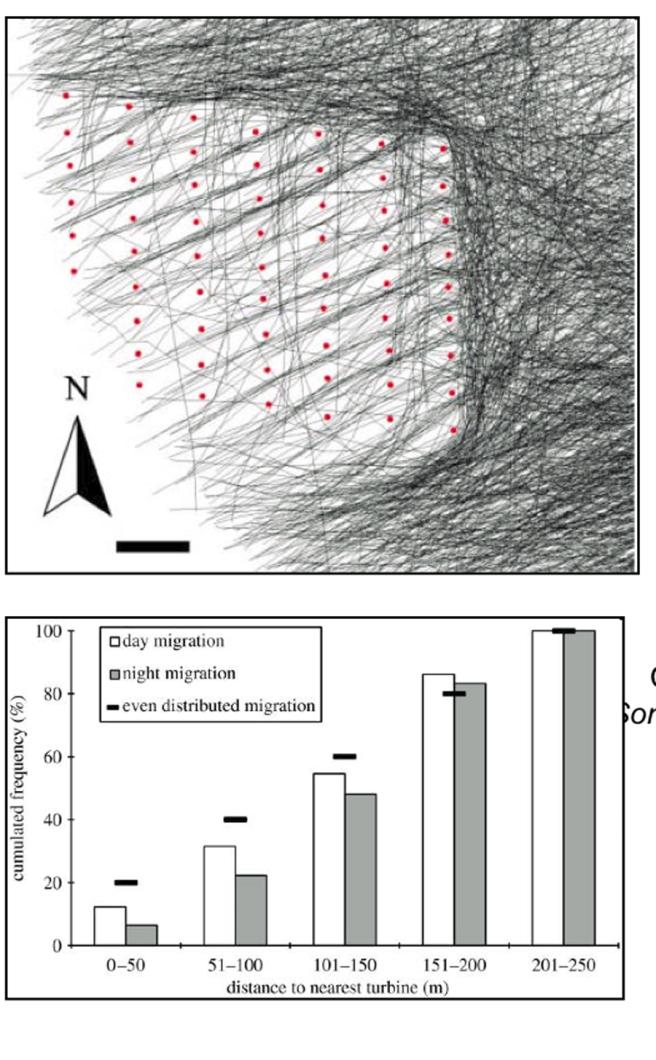

Mr. Paton said simply that placement is everything. And while hard data on the effects of offshore wind turbines on bird populations is lacking in this country, there is a wealth of information from European wind farms to draw from. Radar studies of Denmark’s 70-turbine Nysted Offshore Wind Farm indicate that some sea birds, such as northern gannets, tend to avoid the arrays altogether. Common eiders mainly avoid fields of turbines, except for a brave few who make a beeline through the grid to avoid rotor blades. Among an estimated 235,000 eiders that flew through the grid, it is estimated that less than 50 were killed; cameras mounted on Nysted turbines have run for 2,400 hours without recording a collision.

“Collision mortality does not seem to be a major issue for offshore wind farms and migratory waterfowl,” Mr. Paton concluded.

More troublesome, he said, is the prospect of habitat loss and displacement. Birds who avoid large swaths of the ocean occupied by wind turbines also relinquish large areas of productive feeding grounds. This has already been observed in European populations of black scoters, which have abandoned their former offshore haunts near Nysted, returning only recently and then hesitantly and in smaller numbers. For this reason authors of the Rhode Island management plan advocate avoiding construction in water depths of 20 metres or less, where diving ducks forage. A large percentage of the Rhode Island management area lies in water more than 30 metres deep.

To assess the risk to local populations, the university team needed an adequate picture of what those populations looked like.

“The objective of our study was to determine where the key spots are for different species of birds in offshore waters in the area,” Mr. Paton said. “If you’re trying to plan where to put wind turbines, you want to know where the most important areas are for the birds.”

Comprehensive data on offshore bird populations did not exist before Mr. Paton and his team from URI took to the ocean in January of last year to document the area’s avifauna. The ongoing work, which includes boat-based, aerial, land-based and radar surveys, documented 121 species in more than 440,000 detections. Sightings included commonly seen scoters, gulls, eiders, cormorants, swallows, loons, gannets, shorebirds and mergansers, as well as migrants such as Wilson’s storm petrels, which breed in Antarctica and wander as far as Martha’s Vineyard during the (northern) summer, feeding on plankton while delicately tiptoeing on the ocean surface.

Land-based, aerial and ship-based surveys also underscored the area’s importance as a wintering habitat for loons. By combining sightings and modeling techniques, Mr. Paton’s team was able to estimate the total number of loons in the study area at nearly 3,000.

“What does that mean?” the scientist said. “If you take all the adult common loons that nested in New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Maine it’s about 5,400 individuals. So 54 per cent of the loons are wintering in the Rhode Island Ocean [management plan area]. It’s really a critical area.”

Like the diving duck species, the surveys revealed that loons tend to congregate in shallower areas, less than 30 metres deep. But not all birds prefer the shallows; as a result many local species of the penguin-like alcids, including common murres, dovekies and razorbills would likely face some amount of habitat displacement from ocean wind farms, Mr. Paton concluded. He said additional surveys of deeper water birds are necessary and planned as part of the research.

The URI team has also been gathering data of bird behavior in flight. In a Block Island radar survey of migrating passerines, a group that includes warblers, sparrows and thrushes, Mr. Paton said the vast majority of birds were flying at altitudes between 500 and 1,000 metres. A five-megawatt wind turbine is approximately 160 metres high.

His preliminary conclusion: wind turbines, if placed correctly in offshore areas, would not have a major effect on seabirds and bird migration.

“Based on the work that’s being done in Europe on waterbirds I think that’s correct,” he said.

Although 28,500 birds are killed each year by wind turbines according to the U.S. Forest Service, and that number is poised to increase with expanded wind development, Mr. Paton put the problem in context. Over a billion birds are killed a year by human-induced causes, with buildings accounting for more than half of that total and another 100 million birds killed by cats annually.

Considerably less is known about potential effects on whales and sea turtles, Ms. Smith said during Thursday’s discussion.

“There have been a few studies on what the potential effects might be on seals and harbor porpoises,” she said, “But a lot of the literature on this is speculative or it comes from other types of offshore construction and activity.”

She said the two biggest concerns are noise, both from construction and in the daily operation of the turbines, and habitat displacement. Limited research on porpoises has shown that the animals tend to move out of the area during pile driving, and return shortly after. Deerin Babb-Brott of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs said the effects of generic construction activities on large marine mammals could be ascertained from studies of sperm whales and oil platforms in the Gulf and even right whale interaction with two offshore liquified natural gas terminals in Massachusetts Bay. But he said nothing is known about the effect a wind farm may have in the middle of a potential migration route.

“There really is not a whole lot known about what these impacts would be,” Ms. Smith agreed.

To attain a baseline of data on whales and turtles the URI team gathered available information from strandings, ship strikes and sightings, and fisheries bycatch records to try to map the seasonal distribution for marine mammals and sea turtles. Ms. Smith said there are plans to carry out their own surveys. In all, her team documented some 40 marine mammal and turtle species in the management plan area including sperm, humpback, fin and minke whales, dolphins and the threatened right whale along with critically endangered turtle species including the leatherback. All species already face a spate of human threats including boat strikes and entanglement in commercial fishing gear.

The issue has taken on a new significance after last April’s sighting of a large pod of 98 right whales, almost a quarter of the known worldwide population, cruising through Rhode Island Sound. The area south of the Vineyard also serves as an important habitat for fin and humpback whales during the summer.

Ms. Smith said under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, any chosen site would require extensive surveys and studies of local species.

Still, some at the meeting found the state of knowledge inadequate.

“Do we have any sense if there are a lot of whales in a certain area, whether that’s a problem or not?” asked Mark London, executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission.

“I guess the short answer is that we don’t,” said Ms. Smith.

Comments

Comment policy »