With Rhode Island Sound now looming as the next frontier for wind development near the Vineyard, the Ocean State’s Gov. Donald Carcieri summed up his state’s energy policy this month with a single phrase: “Spin, baby, spin!”

The governor spoke at Roger Williams University on Dec. 10 at a meeting of the Rhode Island/Massachusetts joint task force formed to address offshore energy projects in waters shared by Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The task force includes representatives from Vineyard town government as well as members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and the Martha’s Vineyard/Dukes County Fishermen’s Association.

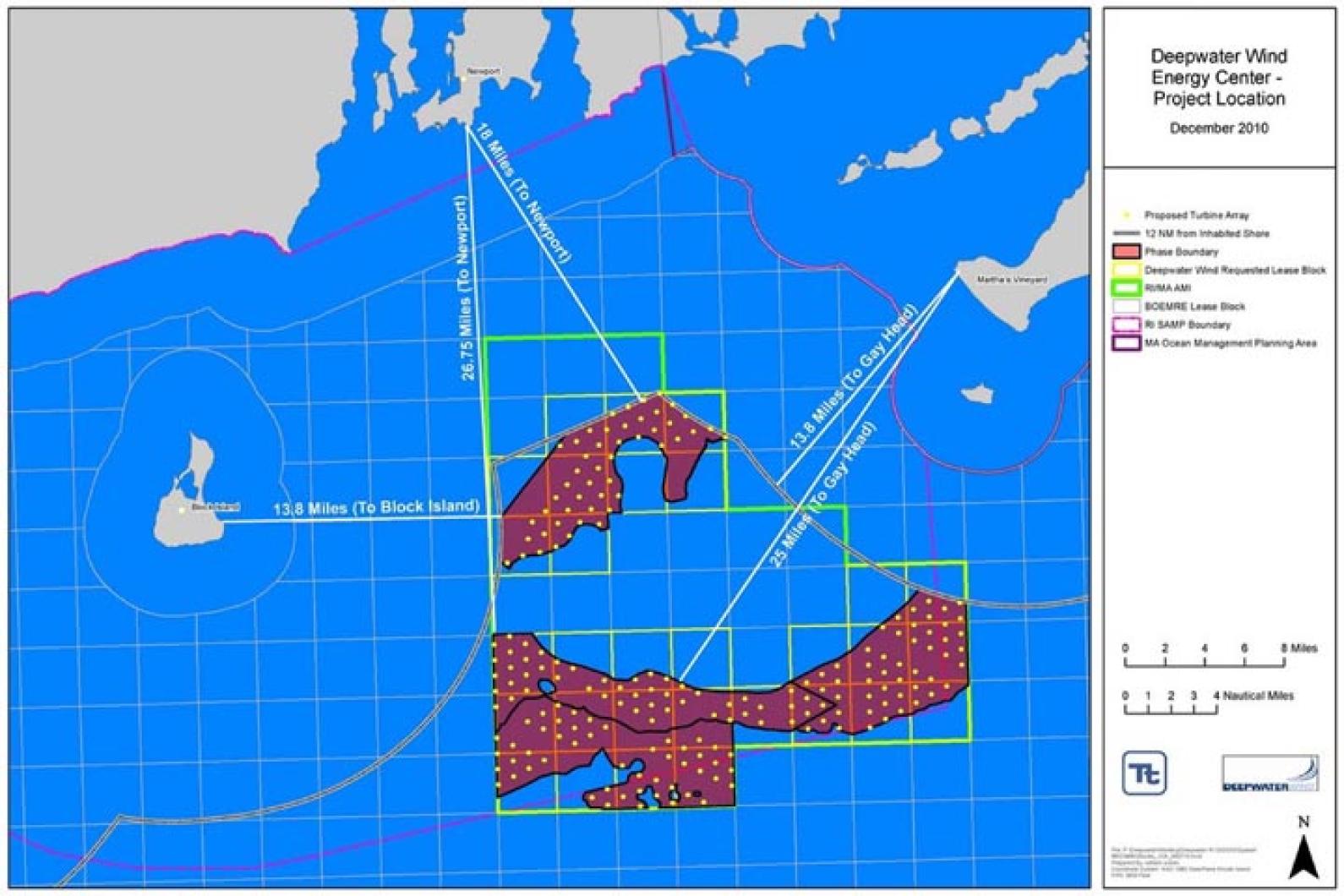

And its work is not simply academic; plans were announced two weeks ago for a 200-turbine 1,000-megawatt energy project by Deepwater Wind — part of which would extend to within 13.8 miles of Gay Head — as well as another unsolicited bid in the area by Neptune Wind. Members of the task force were summoned to the Bristol, R.I., campus to discuss the proposals with the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. The two proposals are currently under review by the bureau to establish their financial and technical viability.

After Mr. Carcieri began the morning with a rote appeal for expanded exploration of offshore energy, deputy assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior Ned Farquhar touted the federal government’s new streamlined “Smart from the Start” permitting process, announced in November.

Skeptical Islanders said they think streamlining is not necessarily a virtue.

“I would like to say that I trust the developer but I don’t believe that,” said Doug Sederholm, a member of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. Under the new process the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management will identify areas most suitable for development based on existing data and rely on developers to gather additional data. The process also eliminates what the bureau believes are redundancies in a permitting process that can stretch up to a decade and daunt potential investors.

In Rhode Island a $7 million effort is underway to study the ecological and economic importance of a 1,467-square-mile area set aside for wind development.

Tisbury selectman Tristan Israel said he was discouraged by the discrepancy between the ongoing research efforts of Rhode Island scientists and the pending bids of potential wind developers.

“This is disconcerting to me because on the one hand there’s a tremendous amount of research going on in this area and in the meantime there are already leases on the table,” Mr. Israel said.

Mr. Farquhar said the federal government was pushing ahead with offshore energy because of what he described as a highly productive “ribbon of energy” that flanked the Atlantic Coast.

“The ribbon is not a red carpet though,” he cautioned. “We need to look for the areas with the lowest amount of conflict. In the western United States we started out with 24 million acres for the potential siting of solar projects, and narrowed that down to only 650,000 acres, or about two to three per cent of the land.” He said the government was currently engaged in a similar process offshore, with the hope of developing 10.3 gigawatts of power from Atlantic offshore wind resources.

“I don’t want to sound didactic,” he said after Mr. Israel suggested removing all areas of the map that would affect fishing or archaeological resources, “but we need to spread the impacts of energy generation. Some communities are going to be hit harder than others, but we’re trying to be as equitable as we can.”

The meeting saw an array of concerns from various stakeholder groups including Indian tribes, fishermen and marine environmental protectionists.

Doug Harris, the Narragansett Tribe’s preservationist for ceremonial landscapes, said the government’s efforts should include a thorough survey of submerged cultural artifacts in the area, which was inhabited in the recent geologic past by American Indians when sea levels were hundreds of feet lower.

“Tribes are often seen as an impediment to these processes,” he said. “We want to be involved from the start. How will we establish historic preservation early and thoroughly?”

Bettina Washington, historic preservation officer for the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), angrily addressed the government employees, reminding them of their forbears’ role in the “genocide” of American Indians. Ms. Washington spoke passionately about what she described as the trust broken during the Cape Wind permitting process.

“You are going to have to work very hard for us to believe in you again,” she said. Ms. Washington went one step further than Mr. Davis claiming that an object does not have to be physical to constitute a cultural resource.

“Just because you can’t find something doesn’t mean it’s not there,” she said.

Mr. Farquhar was diplomatic in response.

“Our commitment to consultation with the tribes is extremely important to us,” he said. “I’m disappointed that you’re disappointed.” The bureau moderator put down consultation with the tribes as an “action item” for future meetings.

The Martha’s Vineyard/Dukes County Fishermen’s Association president Warren Doty pressed the bureau representatives about access to fishing grounds after the turbines are built. Part of the area bid on by Deepwater includes Cox’s Ledge, a favorite ground for commercial and recreational fishermen.

“The question that fishermen ask most often is, what are the restrictions in a wind farm?” Mr. Doty said. “Then we’re told somewhat informally that there will be no restrictions, but I’d like to ask a set of very specific questions and ask that we have specific answers to these questions.”

Mr. Doty asked whether there would be an exclusionary zone around the base of the turbines for fishing and whether the area would be open to net fishing, gill netting, trawling, shellfish dredging, lobstering, sea scalloping, long-line hook fishing or aquaculture.

“A concern among all fishermen is that during the planning stage we can get a promise that there’s no restriction on fishing, there’s no exclusionary zone, you can do whatever you want to do,” he said. “But it’s kind of a casual promise made at a meeting like this. How good is that promise? Is it in the lease? Is it in the operations plan of the developer and is that lease binding?” he added.

“We’ll make a point to engage with fishermen and other entities that have an interest in commercial and recreational fisheries and we’ll work very closely with them,” responded the bureau’s Poojan Tripathi. The exchange was typical of the daylong session.

Ed LeBlanc, a spokesman for the Coast Guard’s Southeastern New England Sector, said it is too early to say how restrictions will affect fishing grounds.

“We’d need to see how far apart the towers are and how the cables are laid,” he said.

But David Beutel of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Council echoed Mr. Doty, saying that fishermen he had spoken with are deeply concerned about the impacts of the proposed wind farms on their livelihood.

“They are terrified,” he said. “This is the area they fish; this is an area that’s important to them. Yes, the whole area has some measure of importance but right there [Cox’s Ledge] is a particularly important area.”

Finally, Chris Boelke, marine habitat resource specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, noted that his department’s dedicated Endangered Species Act staffer, Julie Crocker, had registered concerns about the spotty nature of right whale research in the area, an issue that has been continually raised in recent meetings on the Vineyard.

In January the government expects to conclude its review of the two proposals; a period of public comment will follow.

Late last week Mr. Doty told the Gazette that after the Rhode Island meeting he had been in contact with Deepwater Wind and was encouraged.

“It’s been a lot better than with Cape Wind,” he said.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »