On a balmy afternoon sometime in the 1970s, 19-year-old Cindy Kane found herself sailing across the Kansas countryside in the cockpit of a sailboat. But this was not a dream or hallucinatory acid trip (it was the seventies after all). The sailboat rested on the back of a large semi hauling boats cross-country. Ms. Kane, after graduating from high school early and eschewing college, had hitched a ride from the trucker.

The story told by Ms. Kane to this reporter comes alive just as a piece of her artwork does. There is exquisite detail, a much larger, grander story of which this moment is just one of many gems, there are both literal and symbolic layers to it, and there is her small smile at knowing her audience will be struck by the unexpected juxtaposition of images.

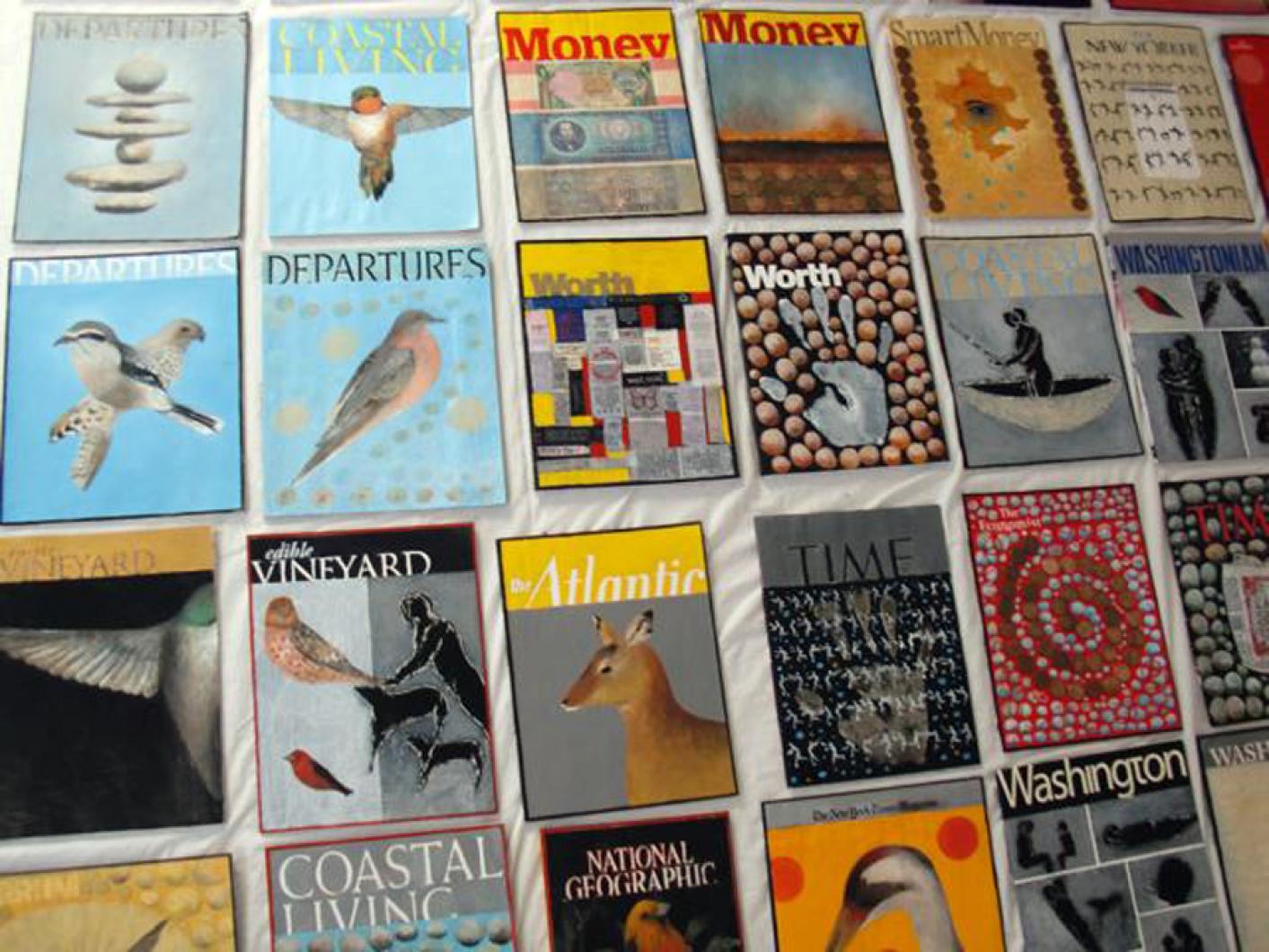

All of these qualities are also readily transparent in her latest show, Covered, now showing at the Cross Mackenzie Gallery in Washington, D.C. The exhibit is made up entirely of magazine covers she painted over with colors, textures, and sometimes found objects. Describing a few of the pieces in the show, the Cross Mackenzie press release reads, “She addresses the bear and bull markets with close-ups of the beasts on Economist covers, she paints melting glaciers on Coastal Living and renders oceans ablaze on Fortune magazine.”

The magazine covers are a bit of a departure for Ms. Kane as she usually works on a larger scale. Perhaps her most stunning piece is the Helmet Project, which showed on the Vineyard at the Carol Craven Gallery in the summer of 2008.

The Helmet Project consists of 50 helmets hanging from the ceiling in a huge circle, each one covered with the notes and “personal artifacts” of war correspondents as well as painted imagery.

“It was a project that was born out of my passion for the dying newspaper industry and the people behind it, the storytellers, the journalists,” Ms. Kane said. “I grew up in a progressive neighborhood outside Washington, D.C. (Hollin Hills) that was full of activism, and that cultivated a longing to do something that had a sociopolitical impact. Then of course when Daniel Pearl was killed, that was the catalyst for knowing that I wanted to make a tribute to journalists through my work as a visual artist.”

Two of the participating Helmet Project journalists were Anthony Shadid and Lynsey Addario, both recently taken captive [and released] in Libya.

“I feel a kind of maternal concern for all of ‘my’ journalists who were generous enough to send me their personal notes and artifacts [when I heard about their abduction] I was beside myself. I’m not like them, I’m not made of steel. They were treated terribly and they barely survived it. I was so happy to learn on the eve of my opening in D.C. that they had been located and were going to be released.”

The Helmet Project was deeply meaningful and having finished such a major project, Ms. Kane was at a loss as to what to do next. It was Lora Schlesinger, her art dealer in Los Angeles, who suggested creating a magazine covers show.

Ms. Kane had been painting magazine covers for a long time but not with an eye to presenting or selling them. “I had always approached them like sketchbook pages. I used them as way to get ideas. I think I was more invested in my larger work, and it took someone else recognizing the quality of the magazine covers for me to view them in the same light...

“I appreciate how the covers feel like artifacts, or relics, and contain information that creates a sense of automatic history. I have always been intimidated by the blank white space of the traditional empty canvas, so I developed a habit or a technique of collecting information, whether it is music sheets, cursive writing practice sheets that I have saved from my children’s schoolwork, or receipts and even paperwork from my pile of bills. I like to lay down this backdrop of information, and then I seem to be able to find my way into the painting.”

This has been true from early in her artistic career. Back in the eighties her work was, as she describes it, “figurative and sort of cave-like. I didn’t use any brushes. I used sponges and gloves to lay down black paint and then quickly etched primitive cave-like figures into it with nails. In that period, I was very interested in the Lascaux caves and Egyptian tombs. That really fed me, that kind of material.”

Her life experiences also fed her. Having moved to Austin, Texas in her late teens, she headed farther west to join the National Park Service. Her stomping grounds for awhile were the Grand Canyon and Yosemite National Park. “You’re very taken care of in those jobs,” she said, “You’re put in a dormitory, treated well. You work in the season and in the winter you travel. I was a vagabond, I was exploring. I didn’t really know what I was, but I was always doodling. Wherever I went, I was identified as the artist before I ever identified it as my profession.”

After Yosemite, Ms. Kane moved to Paris because she had read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, and from there to Berkeley, Calif. where she made the transition from doodler to an actual professional. Having built up a body of work, in 1985 she went to the William Sawyer Gallery in San Francisco, which was known for giving artists their first shows. William Sawyer gave Ms. Kane her first successful show.

That same year, while visiting New York city, she dropped off some slides at the Littlejohn-Smith gallery in Soho. “I left my slides behind the desk with a man there named Richard Meinking, [leaving] just my name, with no contact information. I came back about a week later to collect the slides, because I assumed they weren’t going to want to do anything with them, and he said, ‘Why didn’t you leave any information? We’ve been looking all over for you!’” They offered her a show on the spot.

Ms. Kane never went to art school, but she is articulate and luminous when describing her own methodology and the artistic process in general. “Our feelings are communicated through the materials we work with,” she said. “The act of painting is an act of transformation. The editing of a painting is probably the same painful process as rewriting...

“I tend to work very deliberately in a narrative way, as a series, as a larger work. The worst moments are when I just don’t have ideas. I’m pretty good about staying in my practice and working through it. I paint birds as a way to keep myself in my practice.”

Referring specifically to her current show, Ms. Kane said she had worked on all the magazine covers on the floor of her Tisbury studio and the first time she saw them hung up on the wall together was at the Lora Schlesinger gallery in Los Angeles.

“(Lora) organized them so beautifully in several grids on the wall,” she recalled. “I had never seen them on a wall before. I really appreciated somebody else with a very fine aesthetic eye doing the installation. She did such a beautiful job, they became one piece, they became less about one cover and rather about a whole continuum of images.”

The magazine covers transferred from the West Coast to the East Coast and opened in Washington, D.C. on March 18.

“It was such a wonderful feeling to walk in and see my work in the city of my childhood,” Ms. Kane said. “I’d been longing for that, and this was my first show in Washington. My family came, my nieces and nephews and cousins, childhood friends, my mom, it was really lovely. Some of the journalists from the Helmet Project who were based in Washington were able to come.”

If you can wait until the summer of 2012, Ms. Kane’s work will be shown at the Chilmark Library.

“It’s a space I’ve always loved,” she said, “And (Chilmark librarian) Kristen Hodson Maloney was my babysitter back in Hollin Hills!”

To see the work sooner, visit crossmackenzie.com or loraschlesinger.com or find them on Facebook.

“Facebook has been an incredible tool in terms of the visual arts,” she said. “I have made amazing connections with young artists, young mothers who are struggling with toddlers and also doing beautiful work. Facebook creates a community for them and takes them out of their isolation.”

In addition to the magazine covers, Ms. Kane has been working on round paintings, which will be shown in September at the Cape Cod Museum of Arts.

“It’s harder to sell round paintings,” she said. “It’s hard to display them well, so it’s nice to have the museum there take it on.”

Besides her continued work with covers and circles, Ms. Kane is particularly committed to a new phase, fueled by seeing her magazine covers displayed so beautifully in grids.

“I’m working with the graphic novel format,” she said. “I’m making the story narrative in the form of a comic strip with a grid. I’m a big fan of graphic novels. It took a long time for me to be comfortable with it, but it’s such a dynamic format. I’d be happy to plug the book Good Eggs (by sometime Vineyarder Phoebe Potts) as well as (Vineyarder) Paul Karasik’s memoir. Paul’s was the first graphic novel I ever read.”

That’s not to say she is constructing a traditional graphic novel. Rather than developing a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end, “I just see a grid in a random way that makes sense to me while I’m working on it. And maybe the grid is in reaction to those damn circles, which are so hard to deal with.”

What does this multiplicity of work say about where she is now as an artist?

“It shows that my muses are active,” she said. “And I’m very happy with that.”

On the Island, Cindy’s work can be seen in her studio and at the Louisa Gould Gallery.

Comments

Comment policy »