This month scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution will descend on Edgartown with a sonar-equipped waverunner to map, in unprecedented resolution, the ever-shifting sands and currents of Katama Bay. While the bathymetry of the body of water, where change is a constant feature, is of special scientific interest to the Woods Hole scientists, the information is even more valuable for the surprising underwriter of the project: the U.S. Department of Defense.

“As scientists we’re interested in how the tides, waves and currents work together,” said Woods Hole senior scientist of applied ocean physics and engineering Steve Elgar. “What the department of defense wants to be able to tell is what’s going on in an inlet in what they called a denied area. Let’s say the Navy SEALS are somewhere in Iraq or Southeast Asia, they can’t ask the harbor master for a map and they don’t want to get their zodiac stuck in the mud as the sun comes up.”

By understanding the dynamics in a system such as Katama Bay where maps are almost instantly obsolete, the military will be more comfortable modeling the tides, currents and water depths in a hostile environment where conditions are similarly shifting and unpredictable.

The breach at Norton Point is the largest driver of change in Katama’s changing landscape. Woods Hole scientist Britt Raubenheimer said the inlet runs on a 15-year cycle, opening up on the western side of Norton Point and migrating east at a rate of up to 500 yards per year. The institution hopes to return next summer to survey the bay again and compare the changes with U.S. Geological Survey models.

On Thursday, Mr. Elgar showed off the cutting-edge centerpiece of his expedition: Debby, a jet-ski custom-fitted with an antenna (to relay GPS information), gyroscopes, a sonar array mounted to the rear of the vehicle and compartments jam-packed with expensive electronics.

“When people go to the store to buy a waverunner they typically care about how fast it goes or what color it is,” said Mr. Elgar. “We wanted the one with the biggest storage compartments. The guy at the store says, ‘What are you going to put in there, beer?, And we said, ‘Oh no, computers.’ ”

The waverunner, which will allow the scientists to map shallower water than a boat, will putt around the bay and in the open ocean near the inlet at the leisurely pace of six miles per hour in order to insure the finest detail (the closer together the sonar pings are, the finer the accuracy of the mapping). Even at that pace the work is still fraught with hazards.

“Think about taking your laptop, sticking it in a Jet-ski and beating the crap out of it day after day bouncing over waves,” said Mr. Elgar. “The electronics can’t get wet and that’s just about the worst place I can think of to keep something dry.”

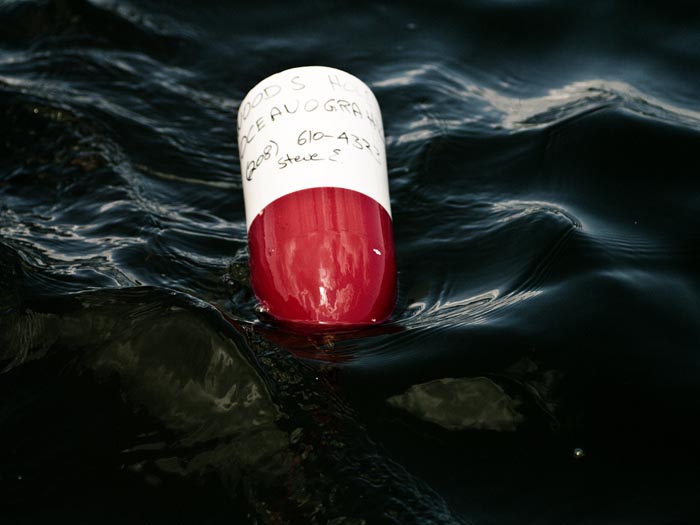

Mr. Elgar has also positioned tidal gauges throughout the bay and a current meter in the deepest part of Edgartown harbor. The tidal gauges cost $30,000 each and Mr. Elgar is pleading with boaters to be aware of the instruments that are clearly marked.

While Woods Hole hopes to unlock the secrets of Katama’s restless bottom, for the town of Edgartown the survey will yield more immediately useful data.

“I told them I’d help with mooring or whatever they need as long as they share their results from the survey,” said Edgartown harbor master Charlie Blair. “Anytime you can get the data from these guys it’s a win.”

Mr. Blair said that the survey work could save the town up to $10,000. Apart from aiding navigation through the bay and harbor, and easing the preliminary workload required for dredge permits, the survey will also help Island shellfishermen who have had to rely on outdated maps of the Katama basin.

“This will really help the aquaculture guys because it’s going to have the different currents mapped out,” said Mr. Blair. “They’ll know where the stronger currents are, where the weaker currents are, where the back eddies are, that sort of stuff. The bay has changed a huge amount since the last survey, I would say millions of cubic yards.”

Mr. Elgar agreed that the current state of the bay’s bathymetry was woefully out of date.

“I have some pretty modern charts and down around where the oyster farm is in the bay, close to the inlet, they say things like ‘important shoaling to one to two feet — 1978,’ ” he said, laughing.

Woods Hole scientists hope that the results gleaned from the Katama survey will also help them in their larger study of dynamic oceanography.

“Our research hopefully will be applicable to locations with breaching inlets all over the place, not just in Katama,” said Ms. Raubenheimer. “We’re ultimately interested in how the whole system is changing with time and what the circulation in the bay is like.”

In the short-term, though, Islanders will reap the benefits of Woods Hole’s high-tech sojourn in Edgartown.

“We talked to the oyster farmers and the harbor master and everyone knows the sands are shifting around there,” said Mr. Elgar. “There hasn’t been a decent map made for decades. We’re going to make a beautiful map.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »