A mile and a half off East Chop, 50 feet down, is a 380-foot World War I British freighter laden with motorcycles, steel billets, railroad car wheels, candles and clothes, still waiting patiently for delivery to the front lines in France. It is the Port Hunter and for photographer and anthropologist Sam Low it was a teenage playground.

“We lived on the wreck,” he said. “We swam underneath and into the furthest reaches of the ship. It was a little like being the only visitors allowed in a cathedral.”

Mr. Low and fellow diver Arne Carr recently returned to the Port Hunter to produce side-scan sonar images of the ship which can be seen at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s new exhibit, Out of the Depths: Martha’s Vineyard Shipwrecks.

There are over 100 wrecks surrounding the Vineyard, and many more in the broader area south of Cape Cod known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” Together they are the casualties of a gauntlet of legendary shoals from Horseshoe to Middle Ground to Devil’s Bridge. Prior to the completion of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914 ship captains had little choice but to negotiate the passage, often with tragic results. The Port Hunter, however, was a victim not of the shallows but of crowded conditions in the Sound when it crashed into the tugboat, Covington.

“Any given day there were hundreds of boats sailing through the sounds,” said museum oral history curator, Linsey Lee.

Trying to avoid the German submarines in the open ocean to the south of the Vineyard, and en route to New York from Boston to join a convoy across the Atlantic, the Port Hunter sank after a collision with the Covington on a moonless November night in 1918. The tugboat tore a 15-foot gash in the Port Hunter’s bow, sinking it with more than $5 million worth of supplies. The entire crew, 53 members in all, were rescued.

Now the ship keeps its benthic vigil on the Hedge Fence Shoal and Ms. Lee has labored to document what remains of the disaster. In the days and weeks that followed the sinking of the Port Hunter, Vineyarders salvaged much from the wreck, including many of the 205,797 stylish leather jerkins (sleeveless jackets) and a surfeit of wool puttees that resourceful Islanders would fashion into quilts and irritating long underwear.

“Everybody wore Port Hunters,” says Bob Chapman, a longtime Vineyard native, now deceased, in one of Ms. Lee’s oral histories. “God, I grew up wearing Port Hunters in the wintertime. Itchy itchies.”

Ms. Lee herself has seen relics from the Port Hunter surface in unusual places.

“You could still find candles at yard sales ten years ago,” she said.

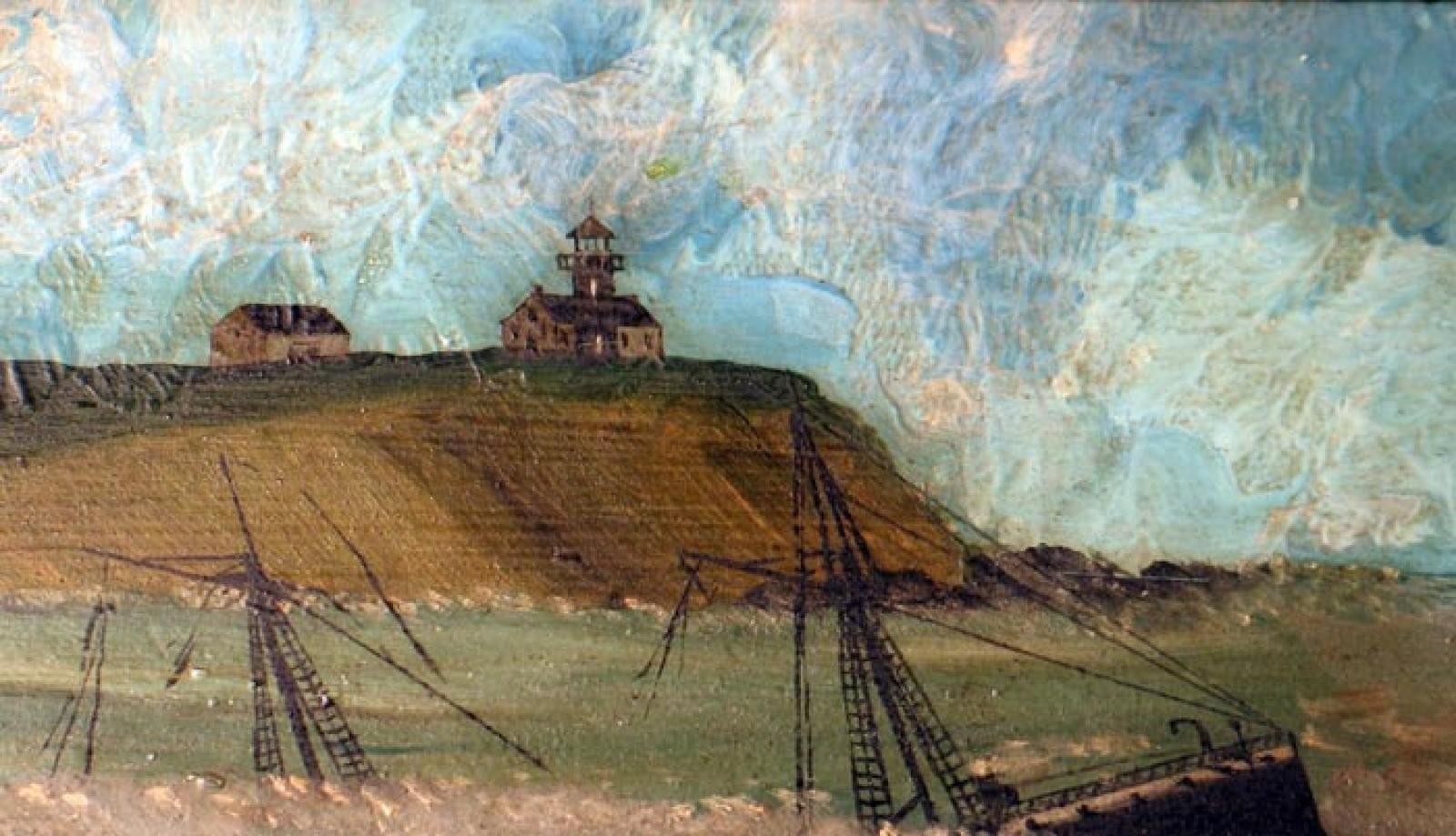

Apart from the Port Hunter, the exhibit also highlights another, much more deadly, wreck, that of the six-masted cruise ship, the City of Columbus, which ran aground on the Devil’s Bridge off of Aquinnah. The boat sank within 25 minutes on a frigid January night in 1884, claiming 103 lives and all of the ship’s women and children. Remains of the 275-foot lavishly-appointed vessel, and the remains of its passengers (who were bound for the restorative climes of Savannah), washed ashore for days. A massive quarterboard that stretches the length of the exhibit gives some indication of the ship’s size, while folk art commemorating the wreck, and fashioned out of pieces of the ship, illustrates the disaster’s affect on the Island population. A playfully carved state room door and velvet seat cushion on display, unmoored from their quarters, evoke the eerie dissonance of leisure and disaster. As an example of the Island’s penchant for repurposing, many of those same cushions lined the pews of the Lambert’s Cove church for decades.

But the exhibit has its cheerful moments as well.

“Part of the story is not only about the unfortunate victims but also the lifesavers,” said assistant curator, Anna Carringer.

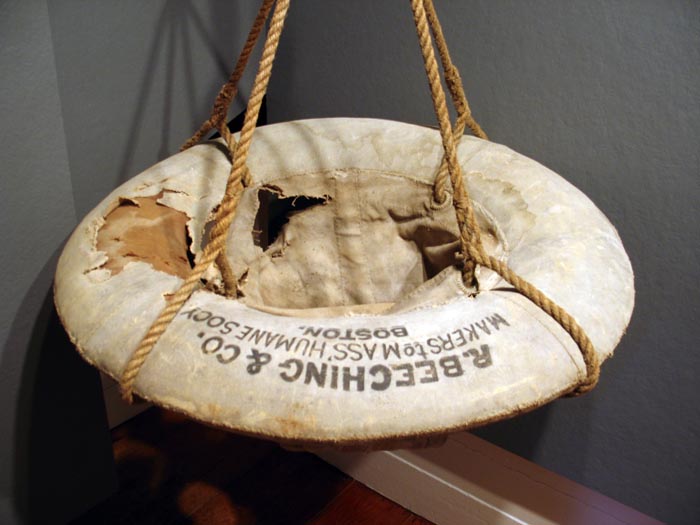

Two Massachusetts Humane Society rescue stations (precursors to the modern Coast Guard) were established, one on Cape Pogue and another in Aquinnah, to respond to the wrecks. A cannon designed to launch rope at foundering ships from onshore is on display, as is a rescue tube known as a “breeches buoy” that would be shuttled along the rope by trained volunteers.

Small human dramas, like that of the resilient Charles Tallman who clung to the rigging of his sunken Christiana off of Cape Pogue in a gale for four days while the rest of his crew perished, are also illuminated. In recognition of his trials Mr. Tallman, who lost his fingers and toes to frostbite, was given the small stand next to the Flying Horses to sell souvenirs and photos of himself.

Ms. Carringer says the dozens of rusting and rotting hulks, frozen in their catastrophic hour in the waters around the Vineyard, are museums unto themselves.

“Shipwrecks encompass all of our human emotion,” she said. “There’s heroism, there’s survival, there’s destruction, there’s loss. It reminds us of how frail and vulnerable we are.”

“I think we need to be reminded of our fragility and we need to be reminded of heroism,” added Ms. Lee. “We need to be reminded that we live in this ocean-bound place.”

On Thursday, Nov. 3, at 5:30 p.m. the Martha’s Vineyard Museum is holding a talk in conjunction with its shipwreck exhibit by Mark C. Wilkins, who will discuss his book The Desperate Crossing of the Sparrow-Hawk. For more information, visit mvmuseum.org or call 508-627-4441.

Comments

Comment policy »