When thinking about tattoos the old cliché of the tattoo dive in a port-of-call and the drunken sailor who staggers inside is never far away. The sailor wants an anchor emblazoned over his bicep on top of a heart with the inscription “Ruthie,” and he wants it now.

And while seedy tattoo joints still cluster in seaside shanties, the profession has progressed, in particular because the younger generation has made skin decoration about as common as dying their hair or wearing their favorite skirt or faded pair of jeans. And to service this new type of tattoo customer it takes a new type of tattoo artist.

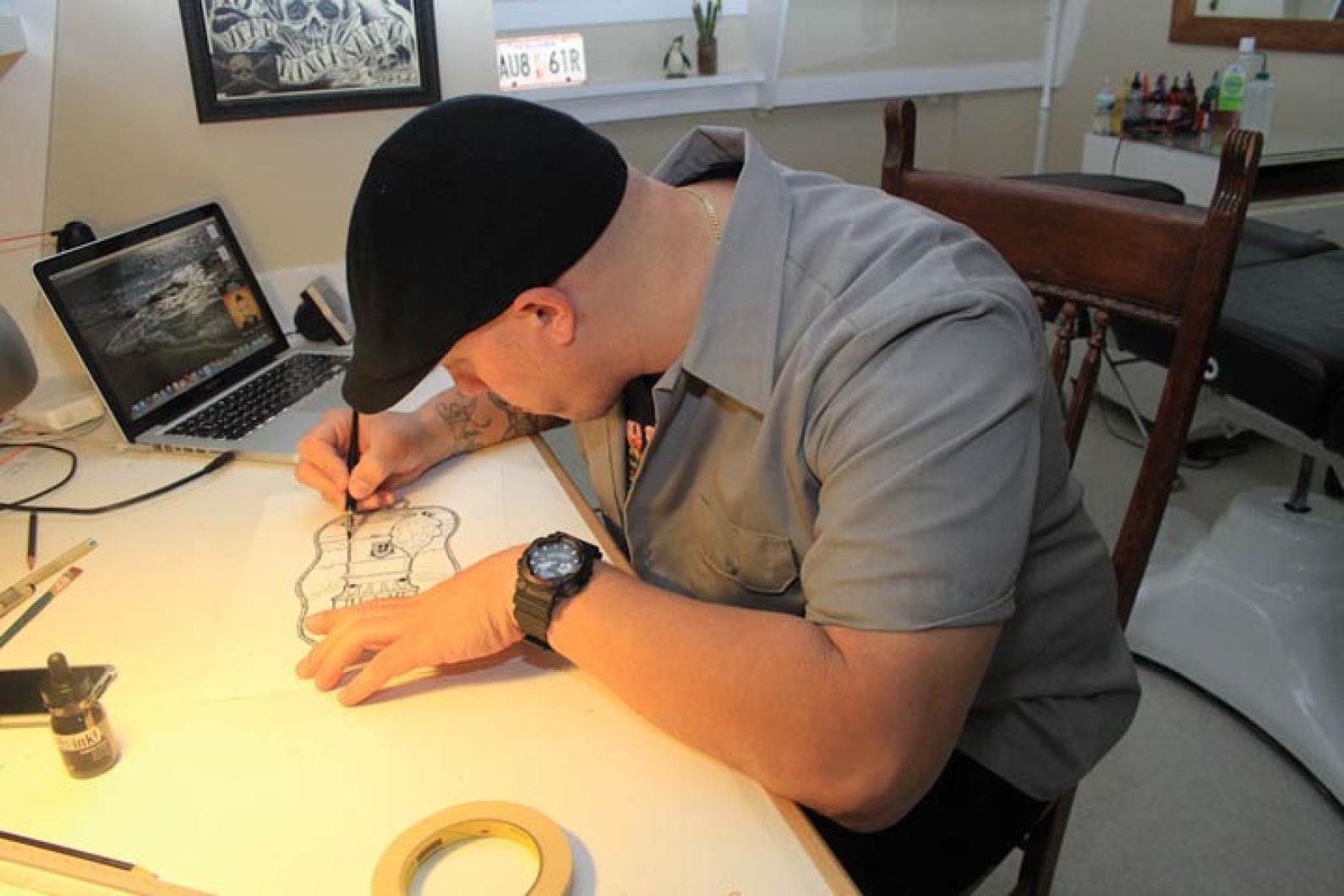

Last spring, Mark (Kito) Fuentes moved to the Vineyard from upstate New York and opened his tattoo parlor at 55 Circuit avenue in Oak Bluffs. Kito began his tattoo tutelage at an early age, long before he first wielded a needle. “I loved drawing cartoons as a kid,” he says at his new parlor while gazing out over his reception area, complete with over-stuffed sofas and carpets and walls painted in soothing earth tones.

Just then his father, Abraham Fuentes, drops by and adds with an impish grin, “His mother and I were constantly called into school because Mark had defaced one of his textbooks. It turned out, when we looked through it, he’d drawn a figure on each page. If you flipped through the book, he’d made an animated cartoon!”

Kito shoots his dad an amused but exasperated look. Abraham waves goodbye, although he’s due back later for a new tattoo. “My family moved a lot [Stamford, Conn., to Utica and Syracuse],” Kito continues. “I started drawing to fill up my time.” He also learned calligraphy at a parochial school in Syracuse.

Many of Kito’s friends received tattoos to mark their 18th birthdays. Kito demurred but admired his buddies’ bravado along with their new, dressed-up skin. Two of his friends opened a tattoo parlor in Syracuse in 1997 that became one of the bellwethers of the art form, Halo Tattoos. At the age of 22, Kito received his first tattoo, an elaborate religious design featuring a biblical crown of thorns, only without the thorns; a more benevolent rendering of the symbol, in other words.

To further his skill as an artist, Kito began attending Monserrat College of Art in Beverly, Mass. “I was only there for a year, but my teachers were great, I did well, it was a very important experience for me.”

Afterwards, he moved back to Syracuse and during the next six years apprenticed at Halo Tattoos, gradually developing his own expertise and style.

It was during this period that his older brother, Bill, moved to the Vineyard to work in the sheriff’s department in Edgartown. After a number of trips to the Island, Kito began to get what the old-timers call “sand in your shoes,” an irreversible desire to live here himself. Ultimately, it was love that sealed the deal. He and Stephanie daRosa, daughter of Dennis and Candace of Chilmark, now live full-time on the Vineyard. Dad, Abraham, has also settled on these shores (Kito’s mother died in 1993).

“Tattooing is a huge culture that people get heavily into,” Kito says. “Most people, when they start out, ask for a tiny tattoo in a private place. Suddenly, they’re back for something that grabs attention. It’s about self-expression.”

Leafing through photos of his work one comes across a trellis of red roses, an elaborate Virgin Mary with clouds, and a classic Sailor Jerry design, named after the mid-20th century tattoo artist who redefined the form with patriotic symbols and stylized cartoon characters such as Betty Boop. Kito’s version depicts Stars and Stripes and the Statue of Liberty.

There are also magazines like Skin Art and Tattoo Artist displaying models with full sleeves of tattoos or elaborate designs on their backs or necks. “About seventy-five percent of my clientele these days are women,” he says. Most women now prefer designs on their hips, upper backs, and on their ribs, he adds. “The lower back tattoo has gone out of favor after people started calling it the ‘tramp stamp.’”

Tattoos are catching on with an older crowd too, he notes. Last summer a woman in her 70s dropped by to receive a small shamrock on her foot.

Kito feels that the basic ethos of modern tattooing is art collection on one’s body. “People are loyal to one or maybe two tattoo artists, and that’s it.”

Speaking of loyalty, Abraham Fuentes returns just then for his session. His son has already worked up a stencil of which Abraham approves. He lies down on a black leather chair reminiscent of a dentist’s seat minus equipment and sink. With the aid of soapy water, Kito applies the stencil on spirit paper to his father’s arm just below the elbow. Abraham examines the temporary imprint, a sparkling diamond about the size of a chestnut. “Yeah, it’s good there,” he confirms.

Kito dabs on antiseptic and ointment to keep the infinitesimal punctures moistened. He sets up the colors he intends to deploy, red, white, blue, and black. Big Band music swings from the CD player and Kito’s needle (disposable, one per customer) embedded in a small gun-like apparatus, makes a low buzzing sound.

Abraham reclines, his expression stoic, and his son speaks honestly about the amount of pain, or lack of, inflicted: “It’s dull but irritating. Afterwards people tend to say, ‘Is that all?’ or ‘That wasn’t too bad.’”

Twenty minutes later, the job is done and Abraham rises, stiff from arthritis, but suitably impressed with his new insignia, which stands out against an older, drabber tattoo. The new tattoo could serve, he believes, as a walking advertisement for his son’s salon.

There is something infectious about tattoos, and when the question is posed that “Everyone should have at least one, right?” Kito chuckles. “Most people can’t stop at one. It’s not an addiction. It’s an appeal.”

And with that he turns out the lights and closes the shop for the day.

Comments

Comment policy »