The Vineyard in winter is a quiet corner of the world. Head up-Island to Aquinnah, say, and the outskirts of Lobsterville Beach. Most days all one encounters there are the wind, sand and stars. But surface appearances can be deceiving. Follow a certain dirt road, turn right at that old oak tree, left at the large bird’s nest, visible only in winter after the leaves have dropped, and one never knows who or what might be found tucked away in the woods.

For example, living in a house down such a dirt road is a man named Jim Shive, who moved to the Vineyard a few years ago with his wife, Mary Ann. Mr. Shive is a quiet, unassuming fellow who also happens to have launched in May of 2011 a new Web site titled, The Best Live Rock Photos Never Seen.

If there is any hyperbole in that sentence, it rests on the back end. The photos have been seen, just not in a very long time.

“When I shot them they were in magazines,” Mr. Shive said. “I had magazine covers, they were in Rolling Stone and The New York Times, they were in a lot of places. But then there was a gap. At the time, like anything, it was newsworthy but then, that was it. Somehow or other, time went by.”

Mr. Shive’s Web site is an archive of the 1970‘s rock scene, when so many classic artists were just starting out. But really the pictures are more than a mere walk down memory lane. The shots are so personal and emotionally revealing that the artists seem somehow more familiar, as if instead of being stars they were buddies growing up in your neighborhood.

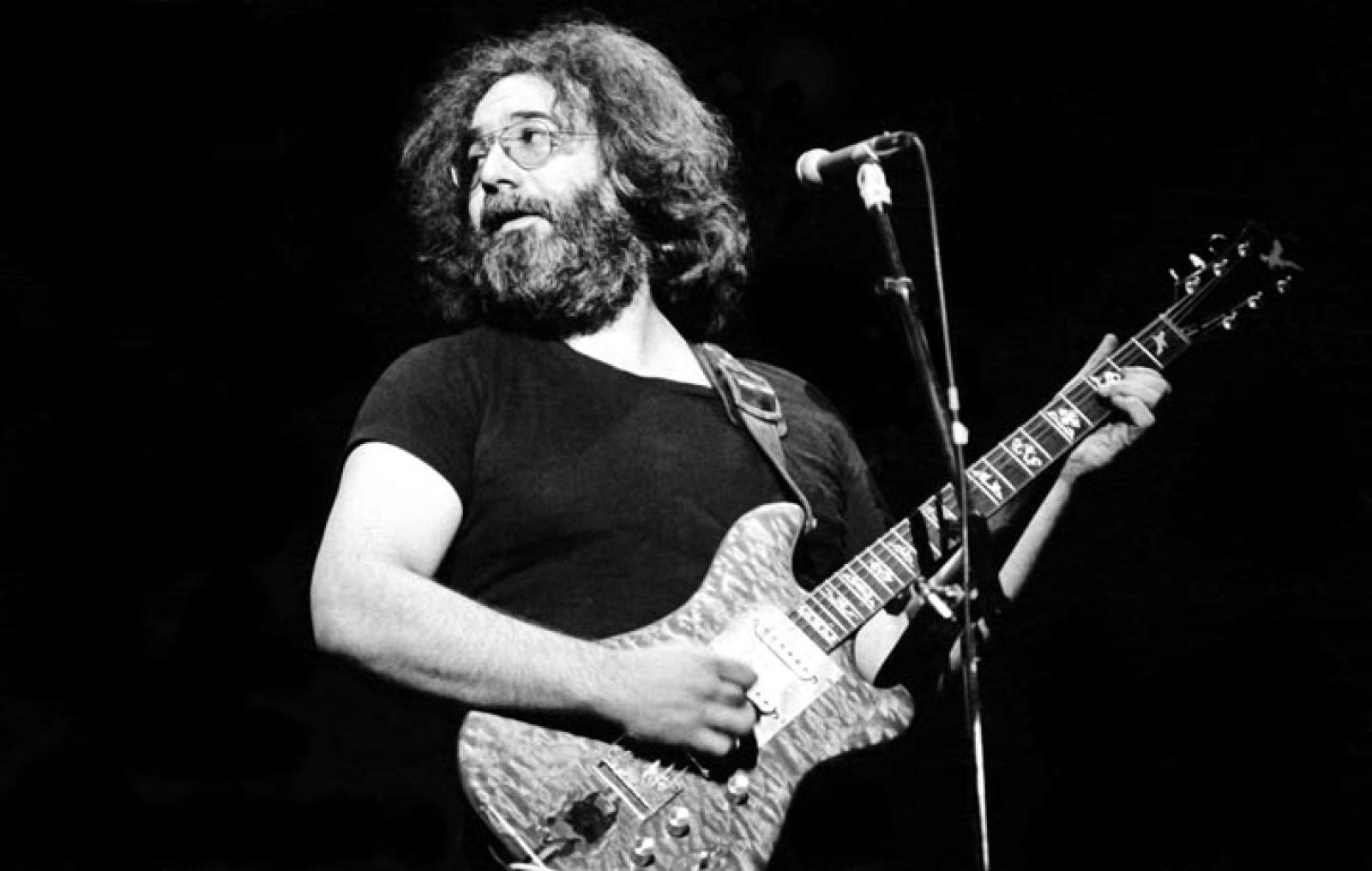

Jackson Brown looks like some soulful high school beauty, you know the one who sat slumped in the back row of class, if he went to class at all, that is. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young are 1970s scruffy, not yet old-men-in-the-woods hairy, but rather twenty-something, indifferent hairy, like those boys who hung out at the 7-Eleven. And Jerry Garcia, playing guitar and wearing his perennial black T-shirt, looking over his shoulder, his eyes twinkling like some black-sheep Santa Claus.

“My wife always says the photos are like live portraits,” Mr. Shive said. “That’s what I tried to catch, a portrait of the person on stage.”

But it is Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band who shine the brightest. After all, Mr. Shive is a Jersey boy and his wife a Jersey girl. By his estimation he has attended hundreds of Bruce shows.

In fact, when The Big Man died last year, it was one of Mr. Shive’s photographs that opened the Clarence Clemons memorial edition of Rolling Stone magazine.

Mr. Shive got his start as a rock photographer as just a pure fan going to see shows.

“Back then a show would go on sale, you would buy a ticket, and you’re in the first 10 rows. I used to come home, write down who I saw, where, who the opening act was, and what I paid for tickets.”

He saw a lot of acts for just two dollars. Front row Bob Dylan tickets at Madison Square Garden set him back $10.50. It was a different time.

At first he didn’t even have a camera with him. Then at age 17 he borrowed a friend’s Minolta and started bringing it to shows and shooting from his seat.

“The first pictures were terrible,” he said. “Number one, I was just learning photography. It’s not like today where you have digital and you can boost your ISO speeds. Back then you didn’t even have high speed film... You throw away a lot of film.”

But he was a quick study, and after high school he majored in photography at Kean University in New Jersey. At first he shot for the yearbook there, cataloguing all the bands coming through on the college circuit. During Mr. Shive’s first week at college in 1974, Bruce played a show as he prepared for his Born to Run tour. He was not yet famous, pulling up with the band in a couple of U-Haul trucks, and playing what amounted to a welcome-back-to-school kegger at a 976-seat theatre.

At the urging of Mary Ann, at the time his girlfriend, Mr. Shive sent some photos to Aquarian Magazine, “a sort of Village Voice for music in New Jersey.”

They bought a shot of George Benson for around $35 and the proverbial light bulb clicked on.

“Back then $35 bucks was what many people worked two days to make,” he said. “Wow, what a way to make a living.”

Making money by checking out live rock shows was indeed a great way to make a living. But by no means was it easy. Pardon the feelings of the digital shooters out there today, but the days of film were the real days of photography, when one had to walk 30 miles to the concert, naked, in 40-below temperatures hauling a moose on his back while a wolverine nipped at his heels.

Well, almost.

There was no auto focus on the cameras, no motor drive, no high speed film, “plus you’re shooting a moving subject in low light from a distance, and there’s a lot of obstacles [monitors, the microphone in the face] with it,” Mr. Shive said.

Harder rock bands brought with them an element of danger too.

“I remember one time I was photographing Black Sabbath at Madison Square Garden. I had the camera up and my elbows right on the stage and there were little round things next to me. I thought they were lights on the stage and the bass guitarist is playing and he looks at me. He’s trying to get my attention, looking at the little round things and shaking his head. Then I realized they were fireworks and he’s trying to tell me they were going to go off at any moment.”

Potentially catching fire or trying to track a constantly moving Bruce Springsteen, that was the job, maneuvering in the pit, looking for that one shot, often watching the entire show through the lens of the camera.

“You’d see it happening, you’d see it building,” Mr. Shive remembered. “You look into the lens and you’re watching the artist and you know them and you’re looking through a certain lens at a certain angle, watching them and dealing with the microphone in their face, just waiting for those components to come together at the same time and sometimes you click and you go, I’ve got it.”

Getting “it” was never certain. The dark room still loomed.

Mr. Shive continued to shoot rock and roll photos for more than a decade. But then something started to shift in the industry.

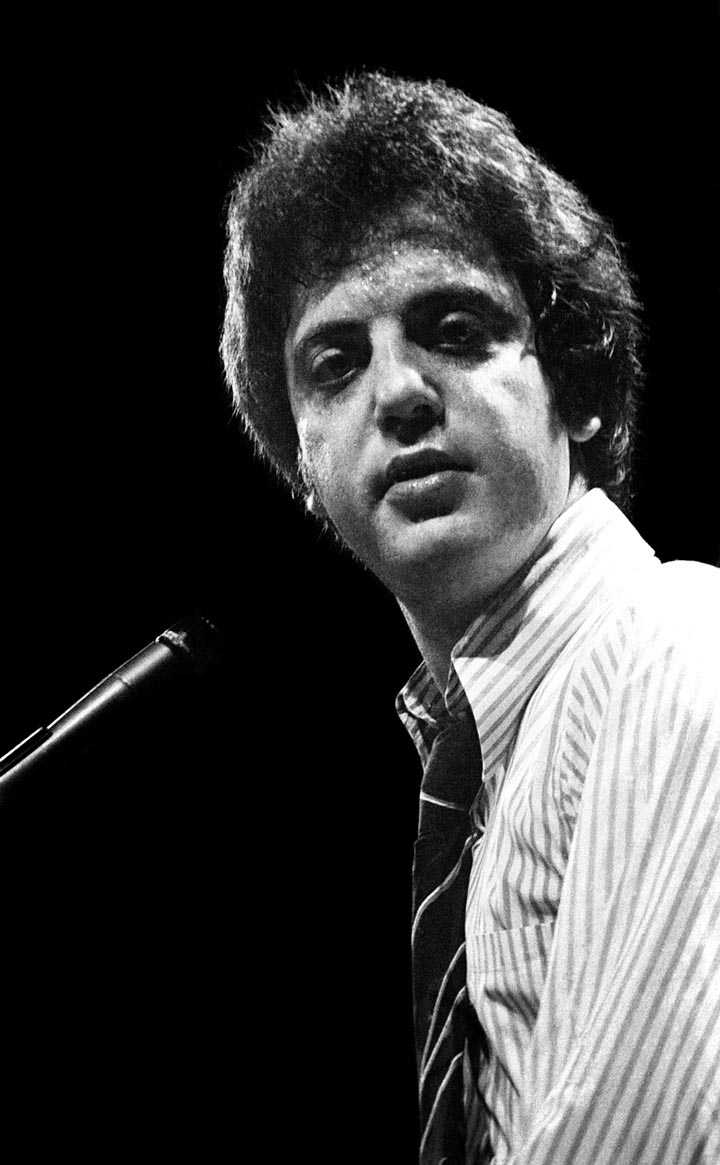

“The one I always remember is Billy Idol, in about 1984 maybe. They give you a photo pass, you could shoot the show, but they [the record companies] wanted to approve the images and if they didn’t like them they were either going to keep them or throw them away. So now you’re giving your copyright away. You’re giving your creativity away.”

He was also possibly giving away the ability to get that one great shot. Bands, or rather their PR firms, started stipulating that photographers could shoot from the edge of the stage only during the first three songs.

“You didn’t have that ability to sit there for the whole show and just wait for that one portrait.”

Mr. Shive decided to turn his back on the world of rock and roll, at least as a photographer. For awhile he shot business stories for newspapers and magazines.

“Then I ended up, as odd as it might sound, in architecture, [photographing] homes, buildings.”

When Mr. Shive speaks about shooting buildings, whether it be large schools or private homes, he becomes almost as animated as when talking about his rock-and-roll career.

But, alas, these stories never end with him caught by Stevie Nicks in her dressing room trying on her hat. Yes, that really did happen.

The evolution of Mr. Shive’s rock-and-roll archive is in part thanks to his son, Ian, also a photographer, who incidentally just won the Ansel Adams prize for his pictures of national parks.

“I had sent him some of the photos and he showed them to some of his friends,” Jim Shive said of his son. “He really inspired it.”

Ian’s friends dug the pictures, had grown up listening to their parents records, and wanted to buy the pictures for their parents and themselves.

“I love the fact that people feel strongly enough to see the pictures and want to hang them on the wall,” Mr. Shive said. Not to mention being able to commemorate Clarence Clemons’s passing through Rolling Stone’s renewed interest.

“Losing Clarence this past year, that’s hard,” Mr. Shive reflected. “It’s going to be very strange to see Bruce without him.”

To view Jim Shive’s photography gallery visit shivearchive.com. The photographs are all available for purchase, some in limited edition.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »