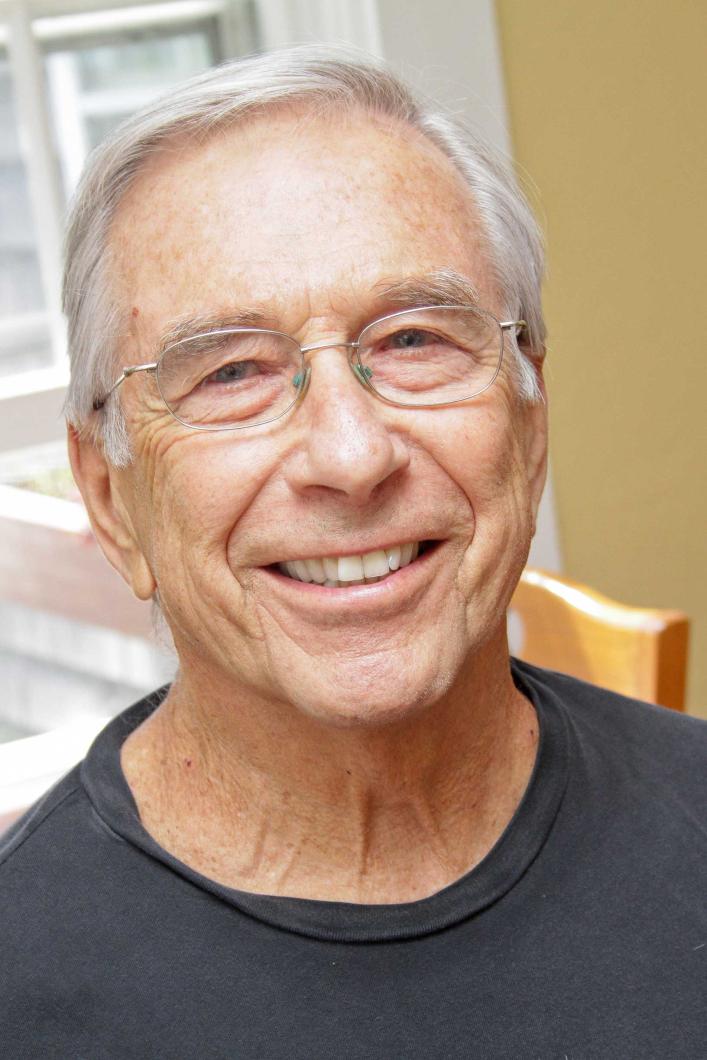

On Wednesday Sam Feldman pulled up a picture of a bathing beauty on his iPad. It was his wife, Gretchen, when she was only 20, the year he met her.

“So, that’s why I was sad and lonely,” he said lingering over the picture before putting it away. “Is that a good enough reason?”

Mrs. Feldman died in 2008, leaving Mr. Feldman adrift and alone for the first time in decades.

“After a wonderful 53 and half year relationship I had a black cloud over my head. I was just filled with loneliness and I sought help,” he said.

But the sort of help Mr. Feldman sought was unavailable. A bereavement support group run by the Island hospice was all women, and Mr. Feldman says that he would have been uncomfortable exposing his feelings in their company. He began to meet informally over lunch with other widowers when the idea of a men’s support group took off.

“We told each other our stories and we cried together, and we said why don’t we start meeting?”

Those meetings began at Mr. Feldman’s house in Chilmark but have grown into a national movement. With 400,000 new widowers every year, and over two million in the country as a whole, Mr. Feldman says that the group is underserved. And he hopes to change that.

In 2011 Mr. Feldman launched a nonprofit organization to serve the needs of widowers across the country. Formerly called the men’s bereavement group (as the group that meets on the Island is still called), Mr. Feldman changed the name of his nonprofit to the National Widower’s Organization after receiving inquiries by people who had lost their pets or a few hundred bucks in the stock market. The group has resources for widowers on its We site, mensbereavement.org, and also puts recent widowers in touch with peers who have already dealt with their own grief. He hopes to revive dormant men’s support groups at national organizations like the AARP and encourage the growth of others nationwide, bringing his experience as a former retail chain developer to help replicate the success of his Vineyard group.

The organization even has academic ambitions. “What we’re interested in now is doing statistical research on the difference between men and women’s grieving and the whole grieving process and how we can help men get through it more easily,” he said. The organization is seeking grant funding to carry out the research and counts on its board of directors’ national leaders in thanatology, or the study of death. “I always think about the horrible personal suffering that I had and how I would like to mitigate it as much as possible for people whose wife or significant other has died.”

Closer to home, on Martha’s Vineyard, the group — which meets twice monthly — has found a following among a wide spectrum of Islanders, from fishermen and carpenters to businessmen and lawyers.

“The eclectic nature of this group and the fact that these people can bond because of the common nature of their emotional trauma is really fascinating,” he said.

But just as the backgrounds of the participants in the support group varies, so to does each individual’s experience of grief. Mr. Feldman says that the Elizabeth Kubler-Ross model of the stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance) is outdated and limiting.

“People come in and they say, ‘Well I’m here,’ and in four months from now I’m going to be there, in six months I’m going to be there. That’s nonsense,” he said. “It goes at its own pace. What we’re trying to do with people is help them accelerate the pace if they can and move on.”

Apart from creating emotional distress, Mr. Feldman says that — at least among the men of his generation — the loss of a spouse also often leaves men completely unprepared for the daily tasks required to manage a household.

“Women are more self-sufficient,” he said. “Men are often thrown into a situation they have no experience in. They don’t know how to cook, they don’t know how to do the laundry, they don’t know how to do the shopping. They’re thrust into this situation. In addition to the loneliness and emptiness there’s this feeling of not knowing how to handle your life’s activities.”

The group is also a valuable arena, Mr. Feldman says, for working out the emotional complications that come with reentering the dating scene.

But the most rewarding gift of the support group is its ability, however meager, to help fill the chasm left by a departed soulmate.

“One of the members who’s 90 years old, after a couple of sessions came over to me and he said, ‘Sam I want to thank you so much.’ And I said, ‘Why? You don’t have to thank me.’ And he said, ‘Before I came here I felt so alone and now I don’t feel alone anymore.”

The Men’s Bereavement Support Group, affiliated with the National Widower’s Support Groups, meets every second and fourth Wednesday from 2 to 3 p.m. in Vineyard Haven. Call 508-693-0993 for location and more information.

Comments

Comment policy »