Waters are swirling with juvenile winter flounder within the Wampanoag Tribe’s hatchery in Aquinnah.

Tens of thousands of tiny little fish, only a few weeks old, are the result of months of work. John Armstrong, hatchery project manager, said the babies are eating well and getting bigger.

The $308,000 project, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is critical to the future of winter flounder, once an abundant food source in Vineyard waters and all up and down the coast, and now in serious decline. It was begun initially as a partnership two years ago between scientists at the University of New Hampshire and the Martha’s Vineyard/Dukes County Fishermen’s Association, the Aquinnah tribe and a crew of volunteers across the Island.

The project goal is to do the science, raise juvenile winter flounder and ultimately release the small fish into Lagoon and Menemsha Ponds by autumn. The researchers have proposed to take the project ahead another two years, which is being considered for funding.

Last week, the hatchery released 100 adult fish south of Noman’s Land that had been harvested and induced in the hatchery to spawn and release fertilized eggs. Juvenile fish were spawned early in April (most of them were born April 12) and are getting daily attention. Mr. Armstrong said they are feeding the little fishes three times a day with rotifers, a microscopic swimming organism that is raised and enriched at the hatchery.

Elizabeth A. Fairchild, a professor at the University of New Hampshire and the lead project scientist, has studied winter flounder for a decade. The Vineyard fish hatchery is modeled after the successful winter flounder hatchery at the University of New Hampshire’s Coastal Marine Laboratory at New Castle, at the mouth of the Portsmouth Harbor.

“The work being done on the Vineyard is exceptional,” Ms. Fairchild said yesterday by phone. This is the first time that a winter flounder hatchery has been done outside of the New Hampshire research center and it is proving successful. “What strikes me the most is the amount of enthusiasm that has arisen. This project has brought people from all over the community. They are all working nicely together,” she said.

On Wednesday, one of the visitors to the hatchery was Robert Whritenour, town administrator for the town of Oak Bluffs. Mr. Whritenour came with David Grunden, Oak Bluffs shellfish constable. Mr. Grunden explained that Oak Bluffs, along with the other Island towns, are playing a big part in the project. The first year of the project called for a lot of hands in taking water samplings of both Lagoon Pond and Menemsha Pond to determine whether the two ponds were still habitable for the young fish.

Mr. Whritenour noted that there are plenty of regulatory measures to prevent overfishing, but little going on about restoration measures. He took a special interest in looking into the tanks with Warren Doty, president of the Martha’s Vineyard/Dukes County Fishermen’s Association.

Winter flounder, also called blackback flounder or lemon sole, was once a highly sought fish in these waters. Due to overfishing and to some extent ecological degradation of inshore waters, there were huge fish declines in the 1980s and into the 1990s. In Massachusetts there is a minimum size of 12 inches for commercial and recreational fishermen. Commercial fishermen are limited to catching 50 pounds of winter flounder a day. Recreational fishermen are limited to two fish a day.

The Aquinnah hatchery, after shifting its role to a nursery, will now continue caring for the juvenile fish until they are released in the two ponds late in the summer. Ms. Fairchild said the fish will be bigger than a quarter when they are released. At that size, they have fewer predators and are big enough to be tagged.

While the project calls for raising and releasing 50,000 fish, it is too early to tell how many are in the hatchery tanks. “Too numerous to count,” is one term used to describe the scale of the project this far. Ms. Fairchild said the fish — still at the microscopic stage — are just too vulnerable at this point of their development to be tampered with in any way. “There is usually a high mortality at this stage of their development,” she said.

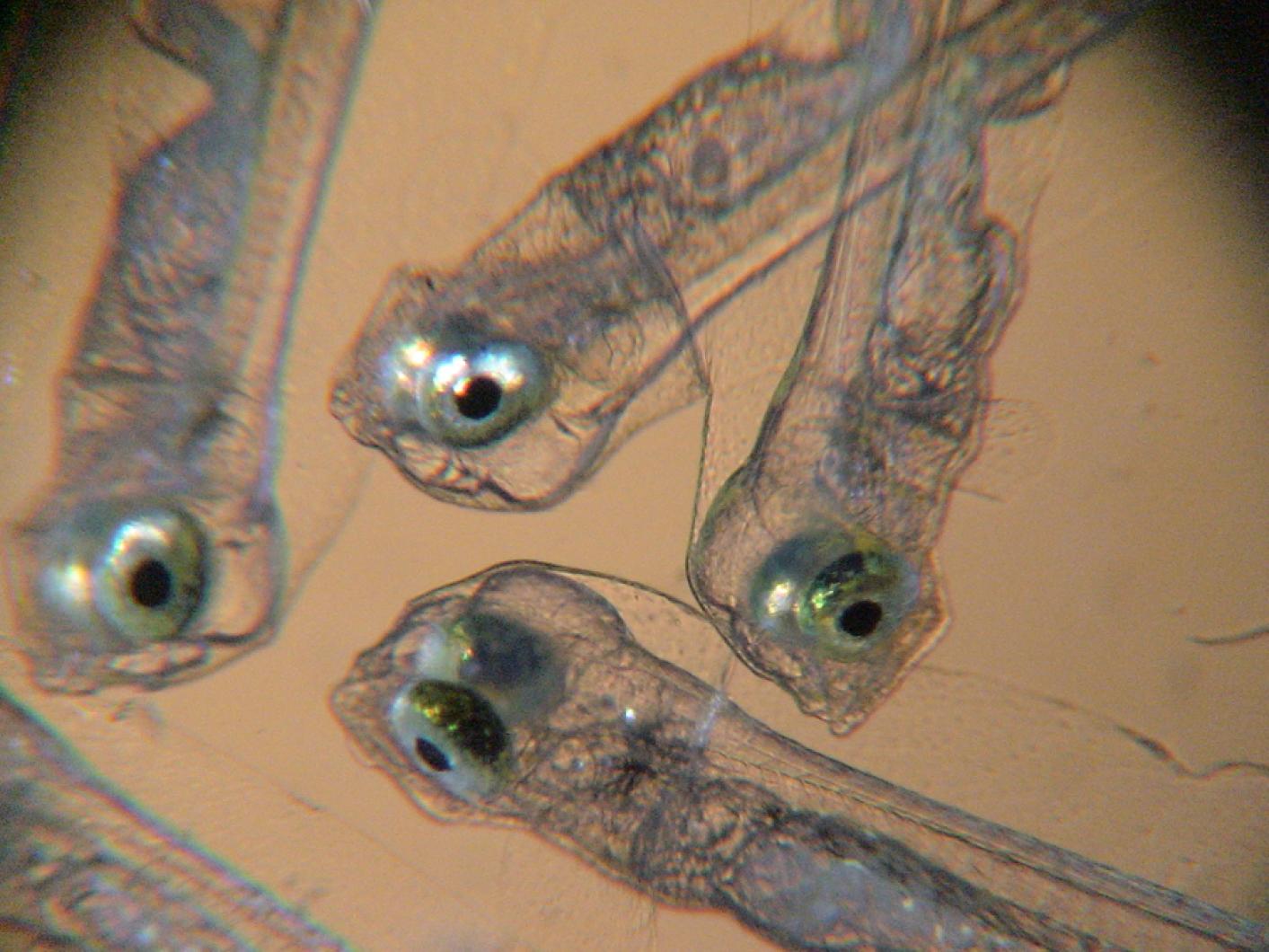

Through a microscope, the animals are partially transparent. They have eyes on both sides of their head, just like any fish. Andrew Jacobs, the tribe’s environmental technician, noted that in the weeks ahead, one of the eyes will migrate to the other side of the fish. Flounders are fish that reside on their side, with two eyes on one side.

Though the project officially ends this October, Ms. Fairchild said they want to spawn more fish and continue monitoring the fish that are released this summer.

“This is really a model,” she said, “for the restoration of other fish.”

Comments

Comment policy »