The class is optional. And yet 162 students signed up to take driver’s education at the high school this year, seizing the opportunity to learn the basics of driving at school, at no cost.

This is exactly what Tom and Barbara Furino hoped for.

The high school driver’s education program is part of their quest for teenagers to have the chance to take driver’s education in school. Their passion is rooted in a personal tragedy: in May 2004, their son David, 17, and his friend Kevin Johnson, 16, were killed in a car crash in Katama.

The couple founded MV Drive for Life, and started advocating for a high school driving class; they say that way students, regardless of whether they have the time and money to take an outside driver’s education program, will learn driving basics before they get on the road.

The couple worked to get the program at Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, where the class was offered for two years starting in 2007. The program was cut because of budget concerns, but it was back this school year, led by former state police Sgt. Neal Maciel and Mike Delis, a retired Edgartown police officer. Both are certified instructors and the owners of the Vineyard Auto School.

The school budget includes $25,000 for the class, and MV Drive for Life has provided three $8,000 computer driving simulators and computer equipment.

“We wanted to get in the school so every child had the opportunity to be able to take it if they wanted to,” Mr. Furino said this spring, sitting with Mrs. Furino, Mr. Maciel and Mr. Delis near the simulators Drive for Life donated. The two adjoining classrooms, a converted chemistry lab, feature a regular classroom space with desks as well as a room filled with computers and driving simulators.

“I always look at it like it’s the one course the school can teach these kids that almost every one of them will use almost every day of their lives,” said Mr. Delis.

“And probably the most dangerous thing they’re going to do for the rest of their lives,” Mr. Furino said.

“And it affects other people around them,” Mr. Maciel chimed in.

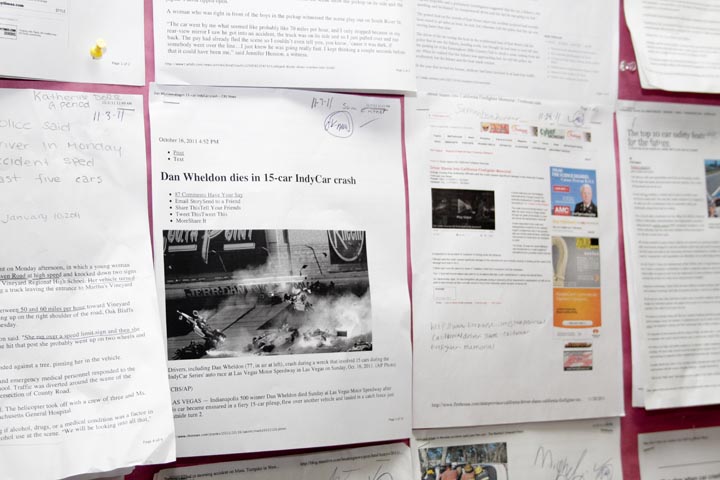

As a reminder of what’s at stake, pictures of Kevin, David and other students who were killed in car crashes are propped up near the simulators. The classroom walls are lined with newspaper articles about car crashes and a sign reads “Buckle up for David and Kevin.” Students donated chairs in memory of their friends.

The class has expanded from 74 students in the fall semester to 88 students this spring. The students register for the class, as they do for other classes, through guidance. The only requirements are that students must be at least 15 years and nine months old on the first day of the course, and that the class fits into their schedule. It is a no-credit class.

“It’s a heck of a turnout for a class that’s . . . not required,” Mr. Furino said.

Teenagers can get a driver’s license at 16, after completing state requirements, including 30 hours of instruction, 12 hours of driving time behind the wheel, and six hours of observation in the car with somebody else driving.

But after 18, driver’s education is not required. Driver’s license applicants must pass written and driving tests, but a class is not required. As the Furinos, Mr. Maciel and Mr. Delis see it, that means too many inexperienced drivers get behind the wheel.

“Basically there’s no basics taught to these kids, and we keep putting them on the road,” Mr. Furino said.

In the high school class, students receive well beyond the mandated classroom instruction component, but students must take in-car driving instruction at a certified auto school (on the Vineyard there is only one, Vineyard Auto, a private-pay school).

“There are going to be children in this class who aren’t going to be able to afford the driving part of the test . . . but once they turn 18, they’re going to go out and get their license,” Mr. Delis said. “Nothing would make me happier than to make one of the kids come up to me someday and say ‘Man, remember what you said? I did it and it worked.’

“That’s what we’re going for, you know.”

Mr. Maciel agreed. “The kids are really pretty good, they understand that this is not a required course, this is a course that has been put together for their benefit,” Mr. Maciel said. “And they all want their license. So they’re pretty attentive.”

The driving simulators, which Mr. Maciel calls “the carrot” of the class, are another asset, Mr. Maciel said, though they are far from a video game; they are penalized, through a point system, for errors. The simulators allow the students to practice driving in 300 different scenarios: fog, wind, rain and snow; night and day; country and city. Students can take a practice drive on a highway, a type of driving they otherwise can’t learn on the Vineyard.

Parents are required to come into the school for a two-hour class. “There are a lot of things we can’t do as a driving school,” Mr. Delis said, saying parents “have a definite amount of responsibility here.”

Mr. Maciel and Mr. Delis shared personal stories from their time as police officers. “We have a lot of personal stories to tell them,” Mr. Maciel said.

Mr. Delis was a responding officer at the crash that killed David Furino. “And when I tell stories about that accident, you could hear a pin drop in that room,” he said. “It’s nothing gory . . . it’s the real truth of what happened in that accident.”

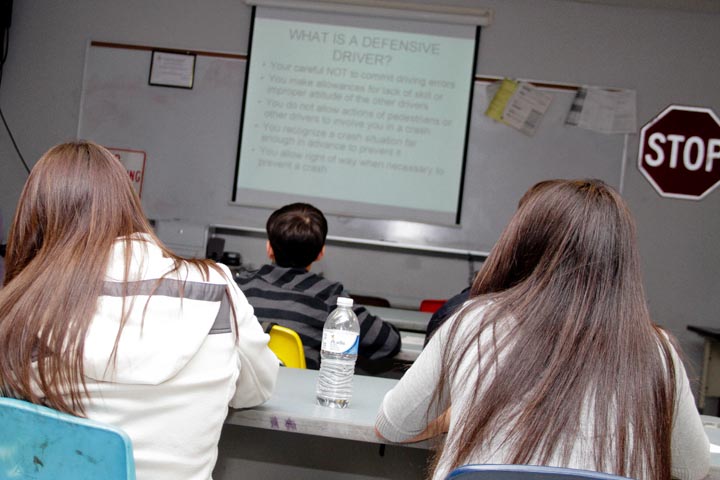

The class melds personal, real-life stories with statistics and driving basics. A few weeks later, Mr. Maciel was in the classroom with a class of 10 students.

“In one year, more than 40,000 people are killed in motor vehicle crashes,” he told them. “The boring stuff is what you’re going to need to rely on when you’re out on the road.”

Later, Mr. Maciel took the class in for a demonstration on the simulator, with one student getting behind the virtual wheel.“Put the car in drive, release the parking brake,” Mr. Maciel said.

“You have no idea how hard this is,” the student said, veering in and out of her lane on the computer screen.

The Furinos hope the class will stay at the high school (it’s already budgeted for next year) and serve as a model for schools across the state. They also are lobbying on Beacon Hill for the passage of David’s Law, which would use a five per cent surcharge of traffic violations to fund school driver education programs.

“I feel this is the most important class in the school by far,” Mr. Furino said.

“It’s the only class that’s going to save your life,” Mrs. Furino said. “Everyone drives.”

Comments

Comment policy »