Finding a new occupation at the age of 45 is either a testimony to necessity being the mother of invention or pure foolishness. Who knows?

Nothing was going particularly well when my husband and I moved to Martha’s Vineyard in 1988. I was exhausted after a having a huge garage sale and then packing up the contents of a 10-room house on the mainland and moving to a summer cottage with six rooms, plus a storage unit that would be emptied when the addition to said summer cottage was completed. My husband was now the business manager for the Vineyard Gazette. After getting things semi-arranged, I started scanning the paper for a job.

In about a week I went on my first interview. A few days later I was hired as a paralegal for a law firm in Edgartown. I had no idea what I would be doing. To tell the truth, what I did for the first year was not very exciting or interesting. Filling in the blanks of mortgage documents and trying to calculate HUD statements was not really what I had in mind for my life. But I did see other people doing something interesting — something I had never actually heard about before even though my husband and I had bought and sold seven houses in two countries. It was something I thought I might like to try. The job was a title examiner.

A title examiner investigates the record history of the land a person wishes to buy to make sure its title is free of liens and is what the seller purports it to be. This is usually straightforward, but there can be interesting little kinks and breaks in what we examiners call the “chain of title.” On Martha’s Vineyard there are many of these breaks and kinks and each one told a story.

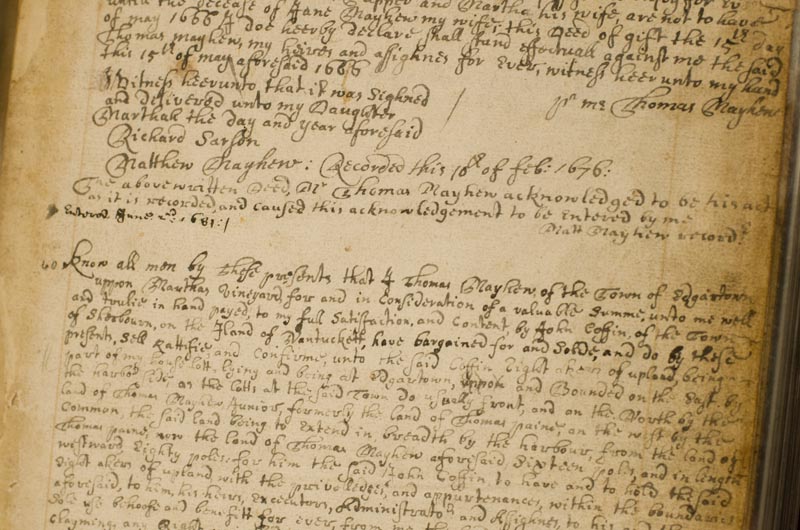

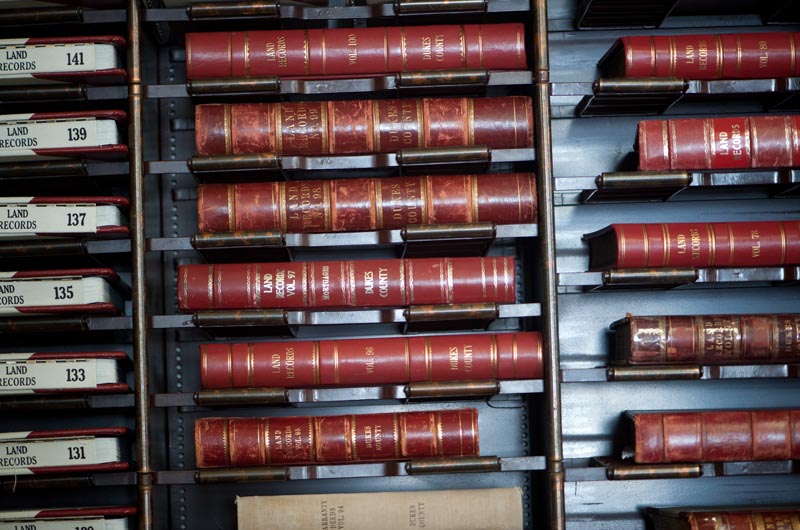

I was as qualified as anyone for this job. It has no licensing requirements and no educational ones either. I worked with attorneys, law students, college dropouts, high school graduates, Phi Beta Kappas, and others with advanced degrees from much better schools than I attended. I was a qualified teacher with a master’s degree and 30 credits beyond that in English Literature. I was a little shocked at times by my new colleagues at the Registry of Deeds, and I learned quickly not to discuss my previous life as the pampered wife of an oil company executive. I also had to modify my wardrobe to allow for the exigencies of working in a room that held dust filled records dating back to 1641. Sitting on the floor in the vault trying to decipher 17th century handwriting doesn’t need a power suit. And I started to wear out my shoes, running back and forth from the office to the Registry.

What being an examiner does require is the powerful need to know what happened and be able to deduce from variations in the standard deed form that something is wrong. A deed can have many defects. The people who give the deed (The Grantors) must be the proper people. The attorney who is either certifying and/or insuring the deed must be insured. The examiner must also make sure the description of the property does actually describe the property and the deed must be properly signed and acknowledged before a notary public. Then the real fun begins.

Every single thing a person owning a property has done to it is of record in Dukes County and has to be looked at. One also has to go to the Probate Court files and check those, too. And you just can’t do this for the current owner. You have to go back at least 60 years and do this for each owner. Sometimes one has to go back even further to find a deed that seems to have no defects. This requires long hours reading tedious documents.

But after years of this reading of a very specialized nature, I began to see stories emerging from the dry facts of property transactions. Sometimes they were sad stories. One I remember came from the final deed of an old Vineyard family to a summer person. The deed out was preceded by several liens placed on the property almost 100 years before by Alley’s store and the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. These liens were for a lot of money, relatively speaking. A $900 grocery bill during the Depression meant a year or more of Alley’s feeding that family. In order to satisfy the lien, the Vineyard family had to sell the homestead that had been in the family for over 200 years. The money would have been applied by the purchaser to clear the lien of the store. Liens on property follow the land, not the owner, so the new owner would have had to pay the liens to get clear title.

Sometimes they were just plain strange like the affidavit regarding a man known only as Mary by his family. He needed to be properly identified so that some family property could change hands. This particular affidavit is a favorite of the local examiners and it is a rite of passage. The search for a long lost identity can be quite difficult.

Sometimes obscure but notable people pop up in the chain. The author of the words to Somewhere Over the Rainbow lived in Chilmark. I also enjoyed learning that Leon Edel, the biographer of Henry James, had title issues in what was then Gay Head. He was a brilliant man who never lived to realized he was not the sole owner of his property.

A deed of an Aquinnah lot was held for a Model T-Ford given to the local Ford dealer.

Long affidavits regarding family history provided clues to what appeared to be strange breaks in the chain of owners. Land that had been forgotten by its owners as well as the local assessors became valuable. I once asked a friend whose father had had enough money to buy this land when it was cheap why he did not do so. He replied that there was no money to be made back then on the land. You might be able to buy it cheap but even after 30 years of holding it you wouldn’t be able to sell it for any more than the purchase price.

Of course, this all changed in the 1970‘s. Land transactions increased as more and more people “discovered” the Vineyard. The books that indexed these transactions started getting bigger and bigger as land that had been regarded as worthless was now highly desirable. The term “grave digger” began to be heard in the Registry. It was not a term of endearment. It referred to strangers (off-Islanders) who came in to the Registry to look for the true owners of a property. Some of these people were dishonest, and the Land Court of Massachusetts barred them from the court. Some of the actions of the grave diggers still burden the land as they sometimes “found” the wrong people. One such grave digger, WIlliam Devine, would go to the court and make a list of all the people who were named in any action to quiet a title. Then he would buy out all these people for a modest sum and proceed to make life miserable and expensive for the petitioner who only wanted a clear title to his land. Mr. Devine was eventually barred from the Land Court.

More often, though, Island families learned they had land they didn’t know about.

My own story is a case in point. Sandy Valley was a woodlot that was owned by the Kidder family. It was left in a will to a daughter, Lydia Kidder Norton, whose children never married. They lived in a large house in Edgartown and forgot about the bequest. As their fortunes declined and the family members began to die, the land languished. In the 1960’s some local fellows purchased the land from her heirs and tried to develop it. It was one of the first of the recent subdivisions. Eventually, the local fellows gave up and Ben Boldt bought them out. Ben was not a popular fellow among title examiners. His transaction records were long and fraught with difficulties. In the case of Sandy Valley, the first deed out from the heirs of Mary Ann (Minnie ) Norton, Lydia’s last surviving child, had a really bad description. But my husband and I had no knowledge of this. I like to think we were just like Leon Edel. We bought a lot in 1977 thinking we would build a house “someday.” Luckily, we decided to build a house early on, and we did have a title examination done. I wondered at the time why it cost so much, but I really didn’t understand.

After I became a title examiner and became aware of the attendant difficulties in buying a portion of some of the old woodlots, I was a little afraid to investigate this on my own behalf. But I did figure it all out and not only was it a relief to learn that there were no outstanding leins, I also discovered that Ben Boldt did not own 100 per cent of the roads in the subdivision. We decided to form a Road Association and made our roads cul-de -sacs just as they were shown on the plans.

A lot of these problems have been cleared up now. Land is valuable enough to care about. Time cures a lot of difficult titles. And time catches up with examiners, too. I am retired now and miss my former colleagues in the “REG”. I still go in from time to time to help out my old firm when younger examiners need their vacations. Sometimes I go in and just to do some digging on my own. I still love the stories.

Comments

Comment policy »