Editor’s Note: In early March the Gazette showed a film of a group of men who motored out from Menemsha to tend a fish trap on Vineyard Sound more than 80 years ago. The film and accompanying story are part of an ongoing project to save and present old films of Martha’s Vineyard on the Gazette website. The film came from a collection of home movies owned by Edith Potter of Chappaquiddick, the oldest of them shot by her father, Charles A. Welch in 1930 or 1931. Relying on a detailed history of trap fishing published in the Gazette in 1959, the story declared that the last Vineyard trap was disassembled in 1941 and that Captain Norman Benson of Lambert’s Cove, who hauled his final trap off Quisset on Cape Cod in 1964, was the last man from the Island ever to engage in the fishery. Wrong on both counts. Story follows.

In the middle 1970s, trap fishing enjoyed a brief revival on the Vineyard on the site of an old Campbell and Flanders trap near Menemsha Bight. Chris Murphy of Chilmark set up exactly the same type of trap that the old-world Island fishermen were using in the 1930s, only he rigged his netting from floating 55-gallon barrels anchored to the bottom rather than using heavy wooden stakes. Mr. Murphy was in his late 20s when he first went trap fishing with a Rhode Island fisherman who also dragged for fish. “And he was, like, the last guy in Point Judith to do it,” said Mr. Murphy of the trap fisherman. “I forget how many we put out — three at a time, I think. We’d put out the traps, and then we’d go back dragging, and the next morning we’d get up early, haul the traps and either go out and tow the net or not, depending on the day. “But I just loved the experience. To me it was like the perfect way to go fishing. It’s like a lobster pot. You put it out there and you don’t touch it for three or four days and you’ve got to assume all three or four days that it’s actually filling up with lobsters. So when you pull it up and it’s empty, it’s disappointing, but it doesn’t change the next day when you wake up thinking, ‘It’s out there, filling up!’ And the fish trap was the same way. Sometimes it did fill up. So that was a good experience.”

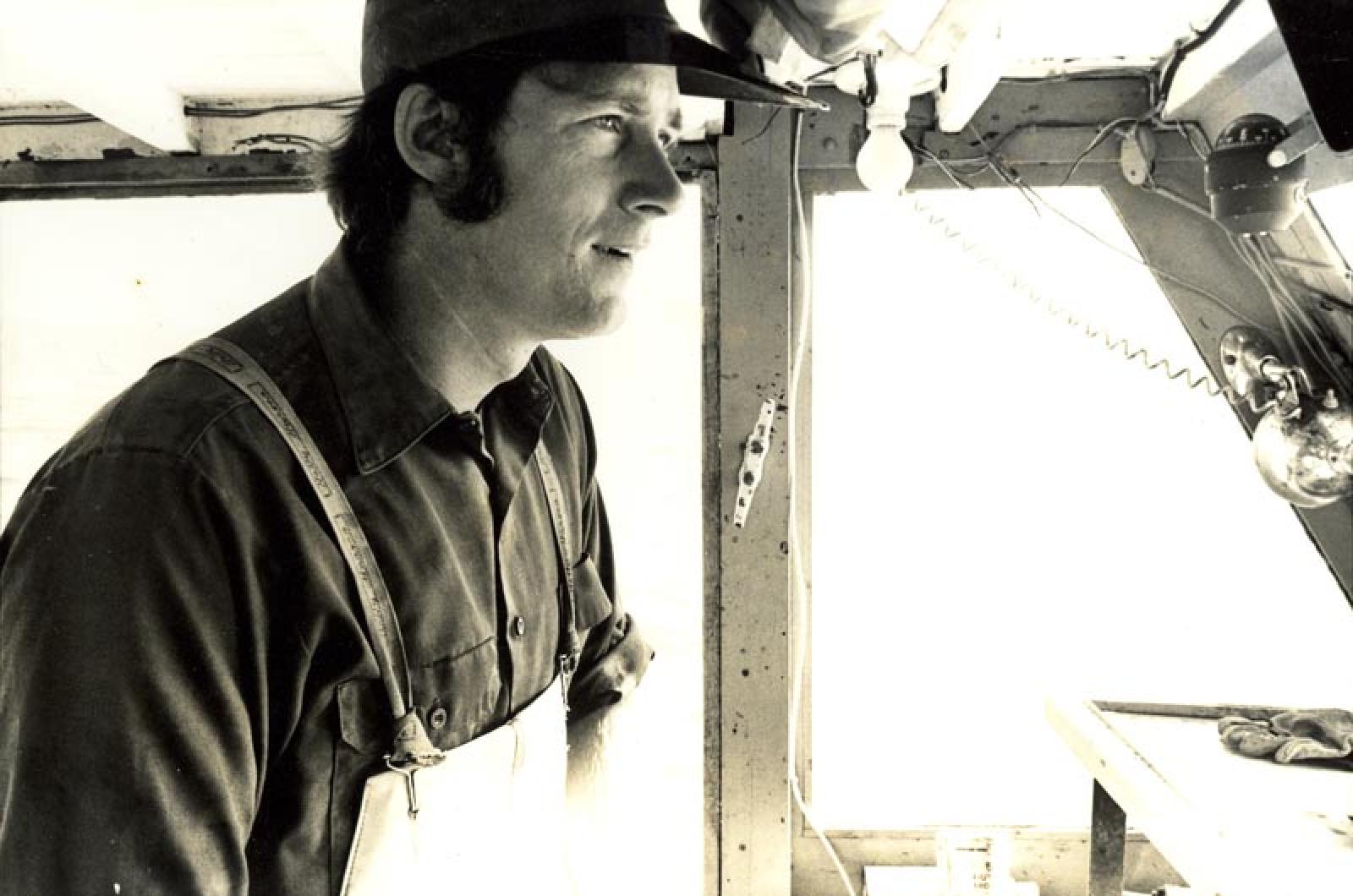

Mr. Murphy bought the trap gear from the Rhode Islander, returned to the Vineyard and set it in Vineyard Sound in the spring of 1975, the first trap to be rigged there in at least 30 years. It lay about a quarter-mile to the east of the Menemsha jetties, and the nets and floats ran a thousand feet from the beach out to the main part of the trap. Working with him from his boat, the Teresa M., were his brother David, Paul Bangs and Dennis vonMehren. Mr. Murphy and his crew eventually set three traps on the sound.

In the 1930-1931 film of the trap fishermen, we see a beamy old skiff known to Menemsha villagers as the Bathtub. The fishermen raise the net at the seaward end of the trap and bail scores of squeteague and scup into the Bathtub, which they also occasionally used to carry nets ashore to mend and clean. Instead of a single, tubby boat, Mr. Murphy employed two skiffs, each 18 feet long, to do the same jobs.

“We would take these two skiffs, tie them stern-to-stern, so now you’ve got a 36-foot open, double-ended boat,” he said. “Just like the Bathtub, only the Bathtub was smaller.” When it was necessary to repair his gear, Mr. Murphy would divide up the nets and carry them ashore in separate boats, which probably made the task more manageable than it was with the Bathtub. “Usually the trap would go into one skiff and the leader would go into the other skiff, depending on how big the trap was and how dirty it was.”

The first day Mr. Murphy and his crew ever checked on his trap, they were astonished. It was full.

“We had 5,000 pounds of scup in it,” he said. “That’s a lot of fish. I mean, my little boat wouldn’t possibly carry it. The two skiffs might, but now what do you do? I was overwhelmed with fish. I mean, I hadn’t really thought about that part. Never occurred to me that it was actually going to work that well. So it caught a lot of fish and the problem was, how do you get rid of them?”

Suddenly Mr. Murphy faced the same challenge in the middle 1970s that the trap fishermen of the movie faced in the early 1930s — crashing markets as the most desirable fish migrated northward in the springtime, reaching the Vineyard late in the game.

“The problem was, the traps in Newport caught fish two weeks earlier,” he said. “Those same fish — didn’t matter if it was sea bass or scup or squeteague, whatever — they’re coming up the coast, moving in and moving north. And as they do, they hit Point Judith, then they hit Newport, and then they hit Martha’s Vineyard two weeks later. So these guys had clobbered the market. The market would start out at a buck a pound. By the time I would get there, it would be a nickel. And you try to stretch a nickel. It’s hard to do.”

Mr. Murphy kept his Vineyard Sound traps going for three years. But like many of the trap fishermen of old, in the end he couldn’t make them pay.

“It went broke,” he said of the venture. “I put it in the barn. Went on with my life. Eventually I sold it to a guy in Connecticut, just off New London. Went down and helped him set it up. And he did really well with it.” The Connecticut fisherman, working far to the west in the springtime, could reach the biggest markets with large catches early in the season. “They’re three hours from New York. Put it all in a pickup truck and go. You can’t do that from here.”

Mr. Murphy believes that despite certain intractable challenges, trap fishing remains a good way to go about it today.

“It comes down to if you’re going to sit still [with a stationary trap], and everybody else is towing a net, they’re going to get the fish before they get to you. Even though this is economically and ecologically much, much better in terms of cost. Because all your costs are fixed. They’re a one-time deal. And ecologically, when you pull this up, and you tie your big boat here, you take your two skiffs and tie them stern to stern, and you lift the bottom of the net and then you bail them out. So if there’s a fish in there that you don’t want to kill, you just pick it up and put it back over the side.” Mr. Murphy notes that traps are still in use off Newport and Chatham today. “Traps still exist, they haven’t gone away, it’s an effective way of working . . . . As far as I can tell, there is nothing new. We just keep copying these old things,” he said.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »