The Charles W. Morgan was known as a lucky ship, avoiding near disaster on numerous occasions during her 80 years of traversing the oceans. And much of this good fortune was the direct result of the care her masters put into her.

A pamphlet published in 1938, while the Morgan was at her home at Round Hill in South Dartmouth, lauds the captains. “It is to their skill, care and seamanship that her immunity from disaster, which overwhelmed so many of her sister ships, is attributable.”

Sixteen of the Morgan’s 37 voyages were captained by Vineyard men — six Island-born and one Down East transplant — including her maiden trip.

“The Vineyard has more than one reason for pride in association with the Charles W. Morgan,” a 1941 Gazette story on the ship’s first sail observed.

Maybe it’s something in the water.

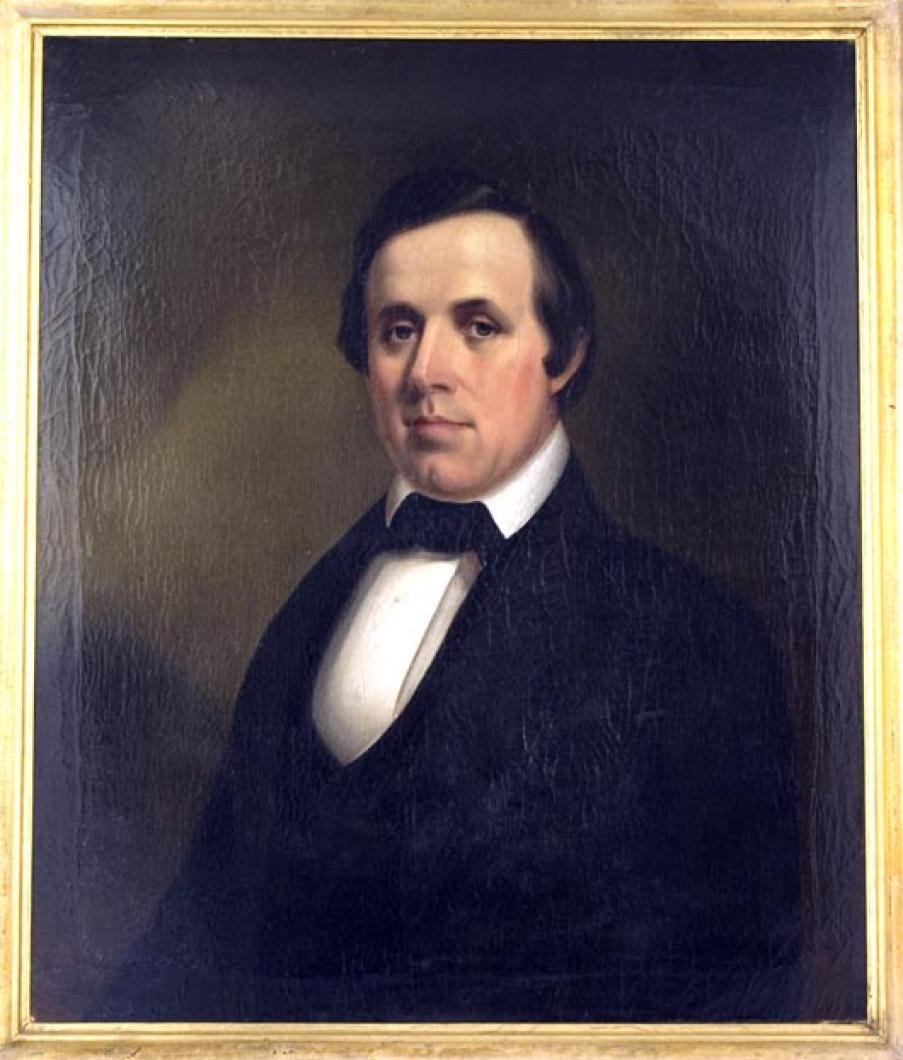

At one point, whaling magnate Charles W. Morgan owned 14 ships, seven of which were captained by native-born Vineyarders. And when it came time to name a captain for his namesake ship, he chose Thomas Adams Norton of Edgartown, a man who’d seen considerable success as both a mate and a master on the whaling ship Hector. Captain Norton was born in 1809 to Thomas Adams Norton Sr. and Louisa Adams. Whaling was in Captain Norton’s blood. Five of his great-uncles had been captains, and he had put out to sea by his early twenties.

Captain Norton kept the family whaling name in good stead, demonstrating considerable bravery in the face of harrowing circumstances. As a mate onboard Hector, while chasing a whale in a lowered whaleboat, he found himself in a unique situation when “the whale himself took the initiative” and rammed the vessel before chasing it for about a quarter-mile. Captain Norton eventually struck the killing blow.

“That Captain Norton was an extremely able whaleman there is no doubt,” the retrospective notes. He was also generous toward the next generation of whalemen, proving himself “truly the sailor’s friend.” A story published in The Sailor’s Magazine just one month after Captain Norton and his crew returned from the Morgan’s maiden voyage, pointed out that he went out of his way to instruct the 20 or so greenhands on board, so that they “came home . . . able to navigate and sail a vessel to any part of the world.”

Captain Norton was also a part owner of the Charles W. Morgan. The first voyage, which sailed the Pacific Ocean from September 1841 to January 1845, returned with a cargo worth more than $53,000. No wonder, then, that Captain Norton retired five years after setting sail on the Morgan at the decidedly young age of 37.

And yet he didn’t forget the Morgan. His first son, Thomas Morgan Norton, was named after the ship, although young Thomas Morgan never sailed on his namesake.

Tristram Pease Ripley, an Edgartown man, helmed the Morgan’s fourth voyage — its first to the so-called Ice Box of the North Pacific, near Russia. Capt. Ripley’s 13-year-old brother Benjamin came along for the voyage.

Emma Mayhew Whiting and Henry Beetle Hough described Captain Ripley in their book Whaling Wives as: “A tall Edgartonian . . . a handsome man with straight mouth [and] features of classic regularity but with a New England accent.” Captain Ripley was also, the authors noted, “suitably bearded.”

It was the second time in three years that Captain Ripley had commanded a ship, having worked his way up the ranks from foremast hand to boat steerer to mate. His previous voyage, on the Champion, set sail shortly after he married Eliza Mayhew, also of Edgartown. In between returning home from the Champion and his taking over as captain of the Morgan, he and Eliza were able to spend just four months together. He left port on Sept. 20, 1853, his 32nd birthday.

Captain Ripley’s sail on the Morgan lasted two and a half years. At the time, whales were becoming valuable not just for their oil but also for the baleen that was used in corset-making. The Morgan shipped 22,700 pounds of bone home over the course of her fourth voyage, in addition to 1,958 barrels of right whale oil and 268 barrels of sperm whale oil.

Though a profitable voyage, his time away from home meant Captain Ripley never met his firstborn daughter, Sarah, who was born while he was at sea and died just ten months later. It was a tragedy that would repeat itself some years later, when the couple’s second daughter, Mary Elise, died of cholera while Captain Ripley was away on a different whaling ship.

Their third child, a boy named Tristram Everett, is described by Ms. Whiting and Mr. Hough as “not strong,” and the Ripleys “may have decided that a sea voyage would be good for the boy.” The entire family sailed together when Captain Ripley assumed command of the Mercury in 1869.

On returning to Edgartown, Captain Ripley settled down into a new house. He purchased a woodlot on Edgartown-Vineyard Haven Road, and bought a new house in town from his brother in law. He died in 1881 in his own home port of Edgartown at the age of 60. Eliza died eight years later.

Captain Ripley’s headstone epitaph sings of the sea. “Drop the anchor, furl the sail. I am safe within the vale.”

The Morgan was fixed up and repaired in order to set sail on her fifth voyage in 1856. Thomas N. Fisher, also an Edgartown man, was at the helm now. John Leavitt, a Mystic Seaport historian, describes Captain Fisher as a strict disciplinarian. He was “one of very few whaling masters to forbid prostitutes on board his ship.” He also flogged two men while sailing on the Morgan, even though flogging had been outlawed some eight years before.

Still, Captain Fisher was a man of some compassion, rescuing a man and his boat adrift at sea while sailing the Morgan through the Pacific. “The man was exhausted,” Captain Fisher wrote in his journal. “I made him as comfortable as I could at that time — took his boat and all things on deck.”

The Morgan was at sea for two and a half years again before returning to port. Captain Fisher next sailed on the Rose Pool during the Civil War. Whaling ships were particularly prone to attacks from Confederate raiders, so Captain Fisher cut off the top of his topmasts, disguising his ship as an English rig and sailing safely home. Logs from the Rose Pool describe a different man than the one who had captained the Morgan, describing Captain Fisher as a man known for his “considerate and human treatment of the crew.”

Captain Fisher built a house on Summer street, but for reasons unknown, lived in Emporia, Kan., for a time before returning to the Vineyard. In 1885, the Gazette archives note that Captain Fisher died of a heart attack in church, “falling over gently into a final repose.”

The Morgan’s next voyage under a Vineyard captain was one of her less fortunate ones, although her commander, Capt. George Athearn of West Tisbury, did return to port with a hefty load of whale oil and bone. The cargo sold for $54,975. But the voyage itself was troubled from the start, leaving port on July 17, 1867 without being properly rigged. This led to strife among the crew and contributed to the high desertion rate for the trip.

One year into the voyage, Captain Athearn developed an ulcer in his ankle while sailing near Tahiti and had to put ashore to seek medical help — the time ashore in Tahiti did not help the Morgan’s desertion rate. Even after treatment, it was several weeks before he could so much as hobble on deck, as Edouard Stackpole notes in his Morgan history.

But Captain Athearn did demonstrate considerable navigational foresight while at the helm of the Morgan. Late into the four-year voyage, he opted to sail south to hunt sperm whales instead of north for bowhead whales. That season, the fleet of whalers that went north ended up crushed by the sea ice. Twenty-two New Bedford vessels were destroyed.

One of Captain Athearn’s own schooners had been wrecked by an Antarctic storm just before he took on the Morgan captaincy, so it is possible that he learned from that experience. A seasoned mariner, he had captained two other ships, including the Emily Morgan, also owned by Charles W. Morgan. His seafaring career is described at length in his wife Amelia’s obituary, published in 1928.

The Athearns were “noted as a family of landsmen, mechanics and musicians, nevertheless this one boy had a longing for the sea and sailed on a whaling voyage while a small boy.” During that trip, young George spotted fur seals while rounding Cape Horn and “from that time on he talked and dreamed about those seals.”

And it was through seal hunting that Captain Athearn ultimately found his greatest success. After returning with the Morgan, he used his proceeds to buy a new schooner and set off for the Horn on the first of three seal voyages. On the third trip he earned $69,000, enough to retire comfortably.

Captain Athearn and his wife had one daughter, but she died at a young age. The Athearns moved to Washington state for a time afterwards, and later moved to Ventura, Calif. Both, however, were buried in West Tisbury.

Standing out amongst the six native-born Vineyarders is one transplant. George A. Smith was first mate on the Morgan’s sixth voyage and became its captain in 1886, as she was setting sail on her 13th trip. Capt. Smith also commanded the 14th voyage.

Born in Eastport, Maine, in 1828, Captain Smith moved to New Bedford at age 20 and began his whaling career. He became a mate on board the Morgan and during the Civil War he was commissioned as an ensign. In 1859, he married Lucy P. Vincent of Edgartown.

In 1869, Captain Smith and his wife set to sea on the whaling ship Nautilus, along with their second child, Freddie. Their first daughter had died just after turning one year old. Mrs. Smith kept a detailed account of the five-year voyage, during which her husband taught her navigation. A thoughtful spouse, Captain Smith planned ahead for his wife’s birthday at sea, and “presented her with a silver pencil case and gold pen,” as Ms. Whiting and Mr. Hough noted.

Still, among his own men, Captain Smith had a reputation for being ill-tempered. One of the greenhands on board the Morgan’s 13th voyage noted the captain’s temper, describing him as “Stuttering George,” as he was known to his crew.

“You knew he was mad when he started to stutter,” Joseph Bement wrote. “The madder he got the more he stuttered.” Captain Smith returned from his first Morgan voyage with a modest haul worth $33,646. A month later, he and the Morgan put to sea again. Captain Smith sailed two more commands after his Morgan tenure before returning to Edgartown. He died in 1891. His son Freddie, who had traveled the world with his parents as a boy, later became a county commissioner.

The sixth Vineyard captain, James A. M. Earle of Edgartown, sailed more Morgan voyages than all the other men combined — nine in all between 1890 and 1908.

As with Thomas Norton, whaling was in Captain Earle’s blood. He was the son of Captain William Earle of Edgartown, and his uncle Valentine Pease captained the ship Acushnet, made famous as the real-life Pequod.

Captain Earle’s early boyhood was spent in Edgartown, his obituary noted but his school days ended at age 11 when he went to sea for the first time as a cabin boy on board Europa, where his father was the mate. But the young Captain Earle nevertheless was an able learner, particularly adept at astronomy.

“In fact he was clever at anything he undertook, no matter what it was” a friend recounted to the Gazette after Captain Earle’s death. “He was a most amiable and kindly man in every way.”

As a child, Captain Earle was a prankster described by Ms. Whiting and Mr. Hough as a lively boy. When he was a cabin boy on Europa, he put copper tacks in the captain’s seat. He also partially tamed an eagle that had taken to following the boat for meat.

By the time he sailed his first Morgan voyage in 1890, Captain Earle was already “widely known in the whaling fleet,” wrote Mr. Leavitt. During a previous command he had taken a whale that yielded more than $150,000 of ambergris, a substance expelled by sick sperm whales that was used as a perfume base.

“He was not only competent, but also had the reputation of being lucky,” Mr. Leavitt wrote. Part of that had to do with “less crew trouble than many masters” as well as “excellent mates and petty officers,” but “much of his luck was the result of forethought and careful study of whales and whaling ground.”

Most of Captain Earle’s voyages were in the Pacific Ocean, from Japan to New Zealand. While in New Zealand he spent time at a school of navigation in Auckland. In 1895, while in Auckland, he was introduced to an 18-year-old woman named Honor Mathews.

“When the Morgan left [after a month] there was a mutual understanding in lieu of a formal engagement,” Edouard Stackpole wrote of the couple. When Captain Earle sailed into port in San Francisco, he was greeted by several letters from Miss Mathews. And on his fifth trip with the Morgan (the ship’s 21st), Captain Earle put in to port in Honolulu for his wedding. Honor Mathews had taken a steamer from Auckland for the ceremony, which took place on Dec. 27, 1895. And then the Morgan continued on its way.

“No bride ever had a more unusual honeymoon than Honor Earle,” Mr. Stackpole wrote.

But Honor Earle was as comfortable as her husband was at sea. She did bring some personal comforts with her on the ship, such as a small piano. And she took up navigation and was often on noon sights on board the Morgan. According to Mr. Stackpole, she was “an excellent keeper of the helm.”

The couple returned to New England in late 1896. Their son Jamie was born shortly after in Whitham, Mass. The Earles spent a fair amount of time on board steamer ships in the ensuing years traveling to visit far-flung grandparents.

In 1902 Captain Earle received a telegram from the J. & W. R. Wing Company, which owned the Morgan. It read: “WILL YOU TAKE COMMAND OF THE CHARLES W MORGAN ON HER NEXT VOYAGE?”

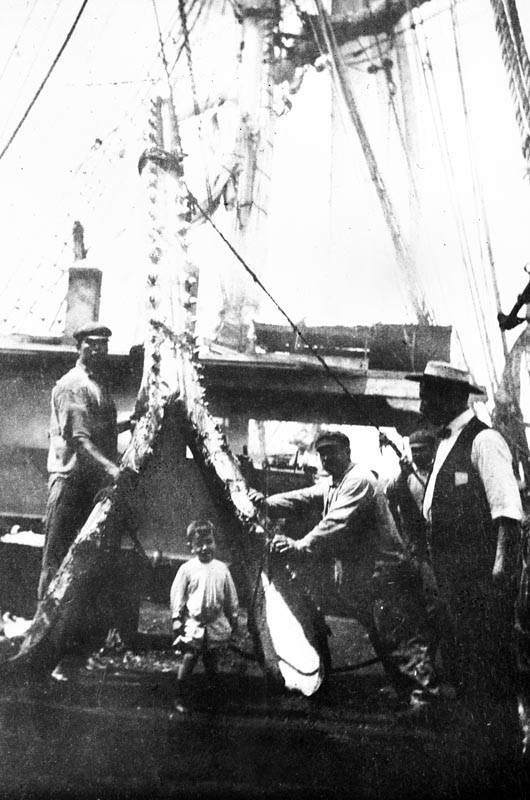

As Captain Earle recounted some years later, the Morgan “had always been my favorite — being remarkably steady, a good sailor, and lucky — if you believe in luck.” He brought Honor and Jamie along on the trip. Jamie was three and, like his father sailing before him, reveled in being at sea. His playground, Mr. Leavitt wrote, was the deck aft of the mainsail, and he slept in a hammock. Photographs of Jamie show the toddler in a cowboy hat, showing off his toy gun.

Honor Earle also joined her husband on the Morgan’s 31st voyage. But midway through that trip Captain Earle resigned due to poor health, handing over the reins to Captain Hiram Nye.

His final whaling voyage was as master of the Alice Knowles. Younger son Norman came along for the trip. And at the age of 53, “after 40 years at sea,” Mr. Stackpole noted, Captain Earle returned home for good, retiring in Quincy. He made at least three visits to Martha’s Vineyard after retirement, and died in 1935.

After three more voyages, the Morgan was left “laid up” for three years, falling into a state of disrepair. And it was a Vineyarder who came to her rescue — 72-year-old Benjamin Cleveland, a man who was almost as old as the ship herself. Capt. Cleveland, of Edgartown, had been master of more than a dozen whaling ships and, as Mr. Leavitt wrote, “knew vessels well enough to realize that the old bark was not yet beyond redemption.” He purchased nearly all of the shares of the Morgan for $6,000.

Even so, the ship needed help if she was going to sail again, and Captain Cleveland ran into a bit of the Morgan luck when he was approached about shooting a film onboard. The proceeds from renting the Morgan so “Miss Petticoats” could be filmed were enough to fund the 34th voyage.

A Gazette profile of Captain Cleveland written by Joseph Chase Allen describes “a short and beamy man, but not stout; a man of iron determination, sometimes called a hard master yet somehow he kept his men for voyage after voyage, perhaps because he was so successful.”

Captain Cleveland had a reputation in New Bedford as a “skipper naturalist,” often bringing back specimens for museums (or his own collection) while on whaling voyages. According to his obituary, published in the New Bedford Standard-Times, he was also for many years the only professional hunter of elephant seals. On a 1907 voyage to the Antarctic in search of elephant seals,

Captain Cleveland brought along a naturalist from the American Museum of Natural History to further the studies. Captain Cleveland brought back about 2,400 barrels of sea elephant oil and 50 barrels of sperm whale oil from that voyage — a very profitable study. Captain Cleveland was married twice. His first wife died some 30 years before he did, and his second wife, Emma, accompanied him on many of his voyages. Captain Cleveland also brought his dog, a black-and-white terrier named Bob, on trips, including his last sea voyage, which he took at the age of 77.

The Morgan’s 34th voyage was in pursuit of sea elephants and sperm whales. In August 1917, as he was returning home to New Bedford with 200 barrels of sperm whale oil and 1,018 barrels of sea elephant oil, the captain received a telegram informing him the United States was at war with Germany. He was in St. Helena, an island in the heart of the southern Atlantic, at the time. U-boats had begun to patrol the Atlantic and, as Mr. Stackpole summed up, “What chance did a slow-moving old whaleship have against one of those underwater wolf packs?”

But Mr. Stackpole also wrote that “the grizzled Benjamin Cleveland had not sailed the Western Ocean for thirty years for naught.” Captain Cleveland relied on every one of his three decades at sea, taking a long route home outside normal shipping lanes and sailing two thousand miles to Dominica. He promptly sent a telegram to New Bedford. “ARRIVED SAFELY. WILL LEAVE FOR HOME ON THE 24th.”

The Morgan had defied the odds, but she was now coming into the range of even more U-boats stationed along the Atlantic coast. Indeed, just after leaving Dominica she missed hitting a floating mine by about ten feet, shifting course just in time thanks to a watchful crew member.

Captain Cleveland then swung away from land, sailing out into the Gulf Stream, adding considerable time to his journey but arriving safely at Nantucket’s south shoals.

“He sailed south of his old home of Martha’s Vineyard to use the covering darkness,” Mr. Stackpole wrote. “His knowledge of the tides in this area was a decisive factor.”

When the Morgan arrived back home safe and sound, cargo intact, she was greeted by nearly a dozen whaling masters at the pier, all thrilled to see the captain home.

Captain Cleveland later told an interviewer that he had, of course, been concerned about the submarines.

“But I had a strange faith in the Morgan,” he said. “You may say what you want about sailors being superstitious, but I know this — the old Morgan was never meant to be sunk by any submarine.”

Comments

Comment policy »