The heath hen’s story of decline and extinction has become inextricably linked to Martha’s Vineyard — so much so that discussions about de-extinction have centered on whether the heath hen could be brought back to the Island. The last heath hen died on the Vineyard around 1932.

But when the heath hen flourished as a species, the Vineyard was just one of many places the bird lived. It was only in its extirpation elsewhere and ultimate extinction that the heath hen’s story converged with the Vineyard.

The heath hen is in the prairie chicken family. It was said to be roughly the same size and shape as a chicken, and was once abundant along the eastern seaboard. By the mid 19th century, the population existed only on the Island.

Sometimes spelled in old Gazette stories as heathen, the bird was said to have bright orange-colored air-sacs on each side of its neck that inflated to be about the size of a tennis ball during a mating dance.

A 1906 account by Dr. George W. Field described the heath hen feeding in an open field on grasshoppers and red clover leaves and displaying “a most interesting series of antics.”

“Frequently two birds, sometimes as much as 100 to 150 yards apart, ran directly toward each other, dancing and blowing on the way, with so-called ‘neck-wings’ pointed upward in V form.”

They frequently returned to the same grounds. “The heath hen, like other species, has an ingrained habit of returning to its ancestral mating ground in the spring,” the Gazette reported in 1929.

The heath hen seems to have made a mating call, a tooting sound described variously as distant tugboats in a fog, wail of the wind spirit, and a blowing in the neck of a bottle that carries further than a gunshot.

As the population became perilously small, efforts began to protect the bird. In 1906, a bill went through the legislature that made it illegal to hunt, kill, buy, sell or otherwise dispose of a heath hen. Violators were subject to fines of $100 per bird.

In 1908, 600 acres of land were purchased for a heath hen preserve. The land ultimately grew larger and became the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest.

The superintendent of the forest, Allan Keniston, was said to keep a careful watch and make daily reports about the heath hen, providing food for the birds and offering $100 to anyone who could guide him to a spot where there were at least three birds.

The Rod and Gun Club had a heath hen committee devoted to the issue. There was debate about what to do, and at times heated argument.

The birds were apparently at their height in 1916, with as many as 800 counted and an estimate of 2,000 made by the warden in charge. The population then rapidly declined to 314 in 1920, 75 in 1922, and 17 in 1924, which was the last year there were any young. By the autumn of 1927 there were seven, all male.

A male nicknamed Booming Ben was considered the only heath hen as of Dec. 8, 1928.

Booming Ben hung on, and was observed over the next few years from a blind at James Green’s farm in West Tisbury. In 1931 the bird was banded and found to be free of parasites. He was in “fine condition and offered tough resistance to the encroachment of science,” the Gazette wrote. “He is aiding the cause of conservation, directing attention to the need for protecting the dwindling species of other valuable creatures and making people think in a way they have never happened to think before of the great unprotected world of birds.”

A Gazette editorial said: “There is no other single bird so famous as this heath hen of ours. He has become a foremost citizen of Martha’s Vineyard and our hopes accompany him from month to month and year to year.”

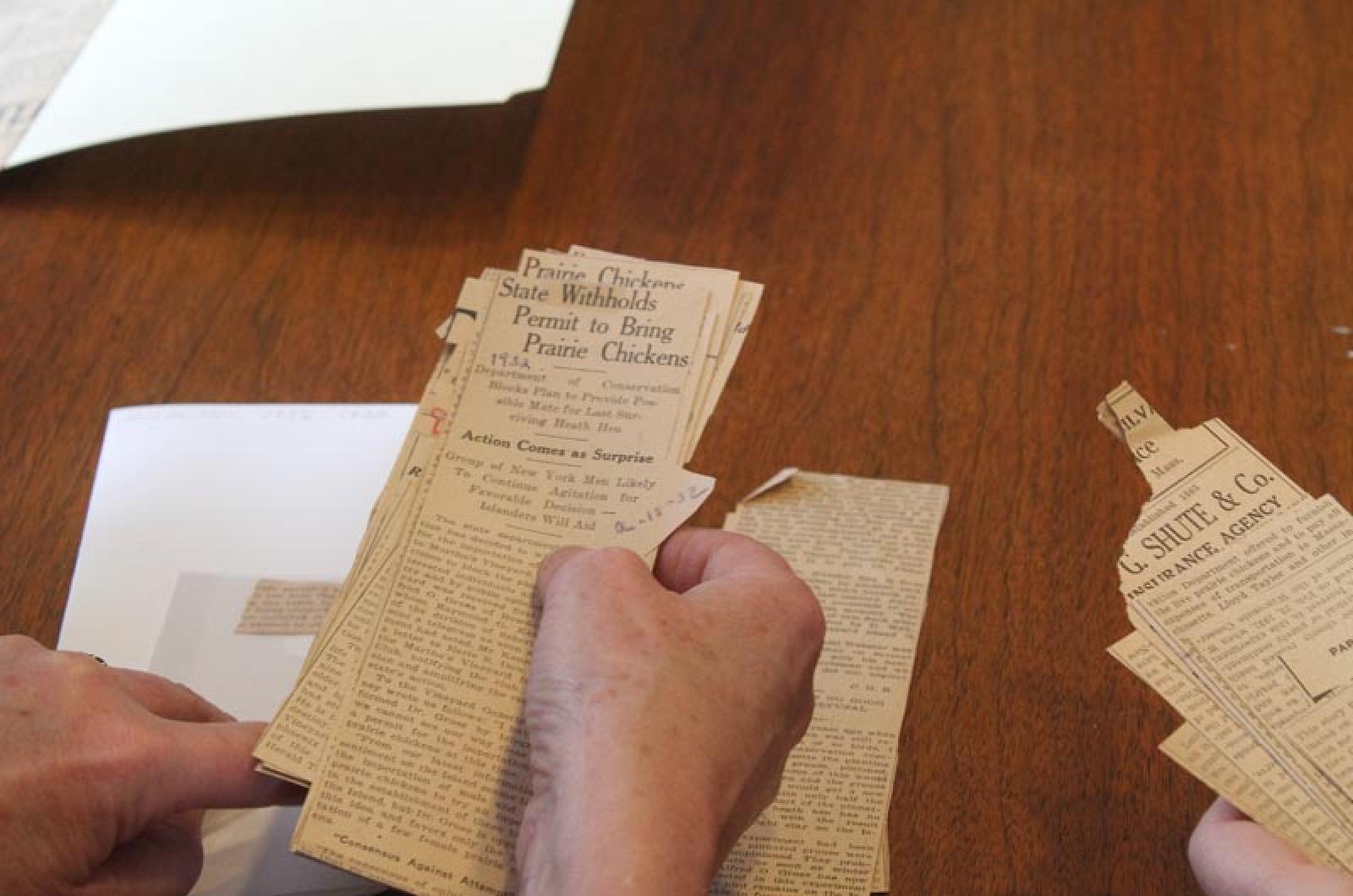

There was an attempt at introducing Wisconsin prairie chickens to the Island to give Booming Ben companionship, and perhaps to allow him to breed. The state refused the permits.

Booming Ben was last seen in the spring of 1932 at the Green Farm in West Tisbury. His body was never found.

Speculation about the cause for extinction was varied, according to Gazette archives.

One possible cause was fire. It is said that female heath hens would not leave their nests, and instead guarded their young only to die along with them. A May 1916 fire burned between 11,000 and 13,000 acres, the Gazette reported, and killed about a tenth of older heath hens and all of the year’s young.

The heath hen faced predators including hawks and cats. The inadaptability of the species was cited, as was excessive interbreeding that led to sterility (the Gazette thoroughly documented the last heath hen’s mating efforts, but also noted he was thought to be sterile).

Disease could have been another factor, including blackhead and dispharaynx, a parasite that was said to be the cause of death of an adult heath hen. Disease would have spread easily among the congregating birds.

In 1926, the Gazette noted the heath hen’s importance to the Island. “Along with the various natural attractions and features of interest, Martha’s Vineyard possesses two which are unique in the respect that nothing resembling them can be found anywhere else on earth. These two are the cliffs of Gay Head and the little, brown heath hen.”

Comments

Comment policy »