The best sports stories are the ones that toe the line of improbability — the ones that unfold in real life without direction yet seem scripted in their narrative, as though they were written for a Hollywood studio.

That was the case in 1972 when actor Bing Russell, otherwise known as Deputy Clem on Bonanza, bought a minor league baseball team in Portland, Oregon after the previous single-A team there had been moved out of state because of low attendance. Where Major League Baseball had seen falling revenues, Mr. Russell, a lifelong baseball fanatic, saw an opportunity.

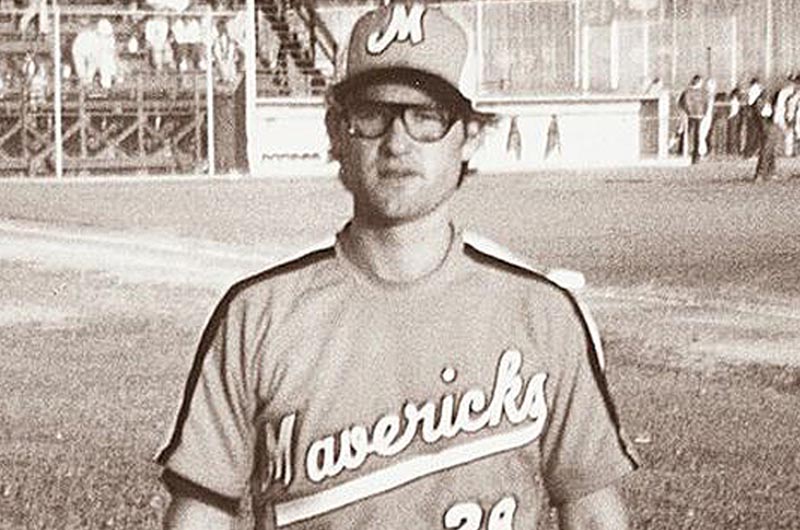

When the team began their inaugural season the next year, the Portland Mavericks were the only independent minor league baseball team in the country; every other team was an affiliate of the MLB. They were managed by a former bar owner. Actor Kurt Russell, Bing’s son, was a team vice president, and the roster was filled via open tryout. The team was a place for dreamers, has-beens, and castoffs — the men who loved the game, but would never have been able to find a home in the farm system.

All Bing Russell told his players, one former Maverick recounted, was to “show up, have fun and play your hearts out.”

Nobody expected them to succeed, let alone post five straight winning seasons and set an all-time minor league attendance record in their final year.

“Did we know there was magic?” said Steven Katz, a second baseman on the 1977 team, and also a Vineyard chiropractor who spends each summer on the Island working with Dardanella Slavin. “Absolutely.”

The story of the Portland Mavericks and their wild ride is chronicled in The Battered Bastards of Baseball, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January and screens next Wednesday as part of the Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival Dinner and a Movie series. Co-director Chapman Way and executive producer Juliana Lembi will participate in a question-and-answer session after the film, along with Mr. Katz.

Mr. Way and his co-director and brother, Maclain Way, are Bing Russell’s grandsons. But even they had little understanding of the Mavericks’ story.

“Growing up, all we kind of knew was that our grandfather owned a professional baseball team,” Chapman Way said in a phone conversation. Four years ago, while visiting their grandmother, he came across a team photograph of the 1975 Mavericks. Some players were drinking beer, others were holding up a dog. It wasn’t a typical photo, but then again, the Mavericks weren’t a typical team. Mr. Way was intrigued. He showed the photo to his wife, Ms. Lembi, and to Maclain. The brothers had dabbled in short documentaries before, but had never tackled a feature-length film.

“It wasn’t a story you could just go and Google, and research,” Mr. Way said. The group headed to Portland for a couple of weeks, poring over newspaper microfilm in the library and printing up thousands of articles. Then they began reaching out to players.

Mr. Way recalled his conversation with Todd Field, who was the team’s bat boy and later went on to become a major Hollywood director, helming In the Bedroom and Little Children. There was no way, Mr. Way thought, that Mr. Field would remember much from his days with the team. But they talked for three hours about the Mavericks. For Mr. Field, being on the team was a life-transforming experience.

“That’s what we got more often than not, how greatly it affected their lives,” Mr. Way said. The film features less than a dozen individuals in the film, hoping to help the audience get to know the characters better. But each Maverick had his own improbable story.

“I adored the game,” Steven Katz said. He’d played ball in college and was in Portland attending chiropractic school when he saw an ad on TV for open tryouts.

“I was in tears, saying why aren’t I there?” he recalled. He worked for a year to get ready for 1977, showing up to the open call only to learn there were 300 players hoping for one of three spots. The odds weren’t great, so Mr. Katz made his own luck: he used his chiropractor skills to help out the men already on the roster.

“I basically made myself indispensable,” he said. Bing Russell initially didn’t want to sign him because he wasn’t as rowdy as the other players, but Mr. Katz got a spot anyway. The day he signed his contract was “the greatest day of my life.”

“I didn’t play much, but it didn’t matter,” he said. “The team was so harmonious, a wild band of brothers. They loved to play.” For everyone, he said, being on the Mavericks was a chance to live out a fantasy. They could play ball again, just like when they were kids. And they could do it well.

The Ways got the sense the story held real universal appeal when The Battered Bastards was unanimously voted into Sundance.

“We were speaking to people from all walks of life,” Mr. Way said of the premiere. “People who had never been to a baseball game got emotional.”

“We couldn’t stop talking about it,” said Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival managing director Brian Ditchfield, who saw the film at the Sundance premiere. “It’s tight and it’s fun and it’s an inspiring comedy movie.”

When it came time to set a lineup for summer, The Battered Bastards of Baseball was an easy decision, and that was before Mr. Ditchfield found out the Vineyard had its own summer Maverick.

“Out of the woodwork came someone from this team,” Mr. Ditchfield said. “After we made our first announcement of the film we made an e-blast at the end of spring, here are some films we’ve booked this summer, and Steve said hey, I lived here, and it was one of those wonderful Vineyard coincidences. That truly sealed the deal.”

“Maybe we’ll have a pickup game before the movie,” Mr. Ditchfield added.

Comments

Comment policy »