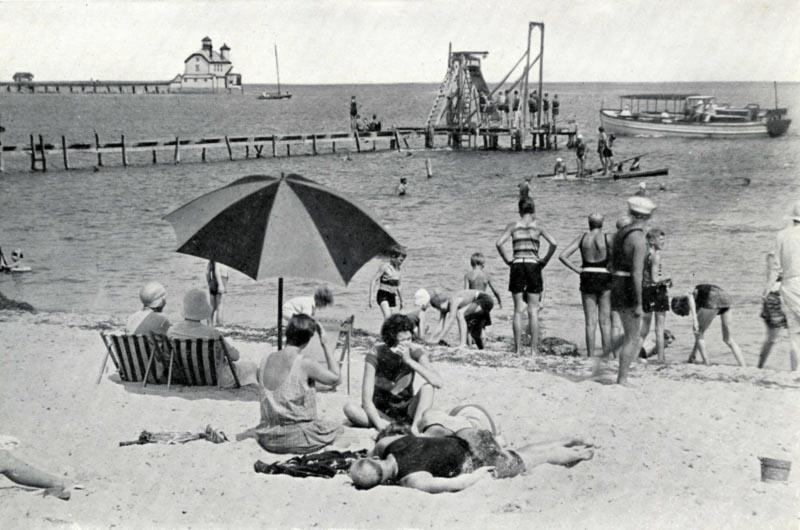

The film was shot at the Edgartown bathing beach on Chappaquiddick — today the Chappaquiddick Beach Club — back in the summer of 1927. And it turns out that people swam, splashed, sunbathed, smiled at one another and flirted with the camera exactly the same way they do now, nearly 90 years later.

That might be an obvious point, but it’s also a revelation if your only experiences of silent movies are the jumpy, sped-up flickers of the Nickelodeon era.

Unlike the mannered theatrical films of Fairbanks or Gish or Chaplin, the young men, women and children seen in this old movie from Chappaquiddick could materialize on the beach today, and in the naturalness of their behavior if not quite the modernity of their bathing suits — fool us into believing that they lived in our own time.

As part of its Historic Movies of Martha’s Vineyard project, the Gazette presents on its website this morning a clip from the ancient bathing beach film. The film was shot by Mr. and Mrs. Irving Annan Chapman, summer residents of Edgartown for much of the 20th century.

The three-and-a-half-minute film clip has never been seen by the public before. It comes from a family collection of 13 films belonging to Lucie Guernsey Kleinhans, a granddaughter of the Chapmans who works as a banker to the media and entertainment industry. She and her husband Lewis Kleinhans live in Litchfield, Conn., and Edgartown, and the movies — shot on the Island and at Chapman homes on the mainland between 1927 and 1935 and kept in the Kleinhans basement for decades — run almost three hours long.

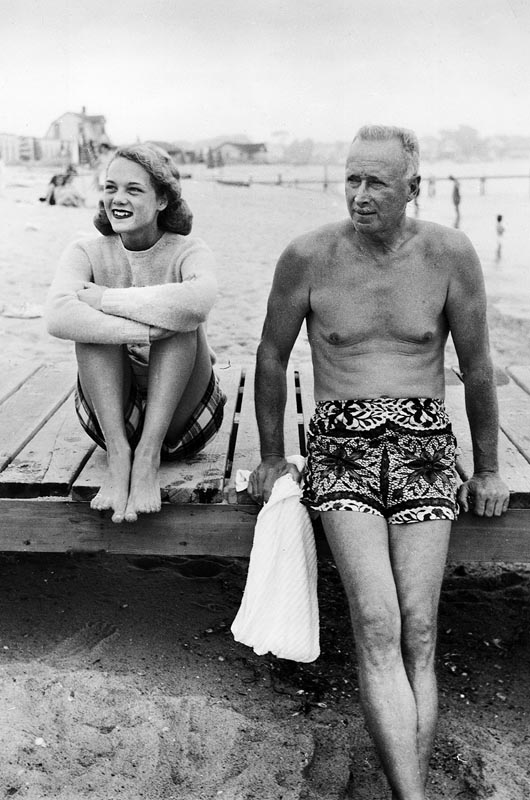

Mr. Chapman, who left his Brooklyn family at 16, worked as an engineer for Pratt and Whitney. He met Lucile Gildersleeve of Portland, Conn., “when she was 12 and he was probably 11 years older than she,” said Ms. Kleinhans. “And he went off to Colorado to get his engineering degree at the Colorado School of Mines. He came back and she was engaged to a man, and he said, ‘No, you’re going to get engaged to me.’”

They married, and Irving and Lucile began to spend their summers in Edgartown, where he had visited since his boyhood in the 1890s.

The Chapman films capture family life at a rented house on Starbuck’s Neck and on brief visits to the Edgartown Tennis Club and other places around town. But most of the footage was shot during a span of eight years, starting in 1927, at what was then a public bathing beach near Chappaquiddick Point.

The Chadwick family of Edgartown established the bathing beach in 1883. Before Bend in the Road and Joseph A. Sylvia State Beach grew popular, and before the stretch of beach became a private club in 1963, the Chappy bathing beach was the place Edgartown vacationers flocked to swim and sun. James Chadwick, an entrepreneur who owned much of the Edgartown waterfront (including the land and wharves belonging to what are now the Seafood Shanty and Edgartown Marine), was a strict Methodist and for many years imposed nearly Victorian standards of dress on the beach.

But by the time these films were shot, mores were easier. Men still wore shirts and belted trunks, and women wore tops that looked almost like blouses. But the film is a catalogue of lean muscles and pretty arms and legs, all proudly uncovered. The Chapman movies offer an encouragingly familiar world to those who know Chappy Point and the harbor entrance today, but they are still refracted by the prisms of history and change.

We see bathers arriving for a day at the beach — but by motor launch rather than a van from the ferry. They wear jackets and ties and summer dresses and pearls, rather than T-shirts and shorts. We see the lighthouse across the harbor — but it’s the old lighthouse with the lamp set atop the keeper’s squat little home. We see children cavort along the shoreline, but in tiny rowboats with paddles, not rubber rafts. From the high dives and ropes and rings, athletic young men and lithe young women execute soaring, splash-free half-gainers in slow motion.

The quality of the bathing beach film is excellent; at a time when cameras were bulky and film expensive, Mr. and Mrs. Chapman learned how to handle both skillfully and creatively.

“It was wonderful to see my grandparents so young and enjoying the [bathing beach],” said Ms. Kleinhans, who sponsored the transfer of her family films and shared a copy of the digital files with the Gazette to review, research and present. She wondered how the bathing beach world of nearly 100 years ago might yet connect with ours today. “The people and their activities, their dress, who they might look like that we know today, and where might they be today. I assume they are all dead, but what happened to them? Are their offspring still visiting the Vineyard? Like me?” she said.

The juxtapositions of formality and ease, of youth and old times, of wealth and rusticity encourage the viewer to get lost in the surface gloss of the Chapman films. But when the footage ends, it gives pause to ponder what the bathers in these living-is-easy old movies did not yet know when they were filmed.

Just ahead of them lie the Great Depression and Hitler. For their children will come the Cold War and the fight for Civil Rights, for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren Viet Nam and terrorism and the perils of a warming world. The Vineyard itself will contend with pressures unimaginable on the carefree beach in 1927 — development, the loss of open landscapes and varied habitats, the collapse of the commercial fisheries and eventually the fight in the face of rising costs to hold on to a viable middle class.

And for the Chapmans themselves, searing losses are yet to come. In 1927, they had two children, the younger an infant daughter named Jacqueline who grew up to be Ms. Kleinhans’s mother. The youngest daughter, Lucile, was not yet born, but though she would one day marry and have six children, she was also stricken with polio as a young adult and spent her life in a wheelchair.

More lamentable was the fate of Henry S. (Peter) Chapman, who was two years old and the first-born son when the earliest of these films was made. In the footage, we see Peter as a little boy with yellow curls happily being buried up to his waist by two friendly young men. Eighteen years later, as a 20-year-old enlisted private in the Marine Corps, he was killed in action at Iwo Jima on Feb. 19, 1945.

“Never did my grandfather speak at all about Peter,” said Ms. Kleinhans. “What happened to my mother and my aunt was, the minute that happened, there was lock down in their lives. They couldn’t get out of their [parents’] sight.”

Mr. and Mrs. Chapman persevered after the war, as so many Gold Star parents did. They rented houses in Edgartown, knew everyone in the summer colony, and her grandfather, who outlived his younger wife by 15 years, “was always involved in family, because he had no family left, because he had left home and his mother and father died. Most people remember him, if you’re old-school Edgartown, and he was just a wonderful guy.”

Mrs. Chapman died in 1965; Mr. Chapman died in 1980. Ms. Kleinhans has given the original movies to Northeast Historic Film, a nonprofit archive in Bucksport, Me. The family films will be known there as the Mr. and Mrs. Irving Annan Chapman Collection.

The Gazette historic movies project began in October 2012 as an effort to save, archive and introduce old Island films to the public before they are lost or damaged. This is the eighth Vineyard movie the paper has presented in the last two years. John Wilson, a television director and filmmaker in Edgartown, edited the clip from a digital file of the Chapman family movies created by Art Donahue of Motion Picture Transfer in Franklin. For more information on the Historic Movies of Martha’s Vineyard project, please contact historicmovies@mvgazette.com. To avoid damage, please do not run an old film through a projector. To see the collection of Island films presented to date, go to mvgazette.com/historicmoviesofmarthasvineyard (no apostrophe in ‘marthas’).

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »