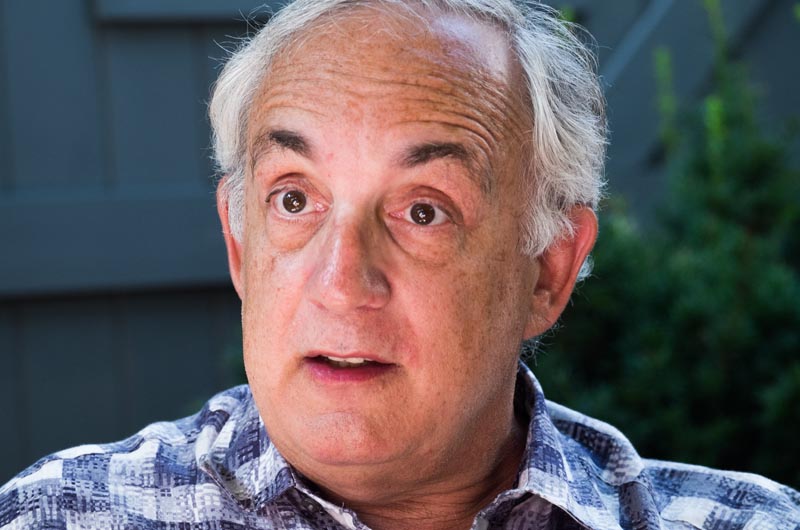

When Mitchell Kapor was 15, he attended a summer science program that changed his life. The program offered hands-on access to computers, which was rare in the 1960s. The experience set the ball rolling for one of the major success stories in information technology.

In the 1980s Mr. Kapor founded Lotus Development Corporation, where he designed Lotus 1-2-3, a spreadsheet program that opened the door to personal computing in business. At Lotus he also first met Freada Klein, whom he would marry many years later.

Today, as partners in Kapor Capital, based in Oakland, Calif., Mr. Kapor and Ms. Kapor Klein now devote much of their time to investing in startup companies that promote social change. Among other projects, Ms. Kapor Klein runs the nonprofit Level Playing Field Institute, which promotes fairness in higher education and workplaces.

Their work together represents a synthesis of ideas and experience, and is built on a network of friends and businesses. Much of that network has developed on the Vineyard, where they vacation every summer.

Vacations are usually a mix of work, socializing and relaxation, they said in an interview over coffee in Edgartown this week. “At sunset we’ll be walking on the beach, but I don’t think we are going to be otherwise goofing off that much,” Mr. Kapor said. This year is their 18th summer on the Vineyard.

A few years after stepping down from Lotus in 1986, Mr. Kapor founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights group, and began investing in technology startups. Ms. Kapor Klein had also left Lotus and was working as a consultant on workplace issues for large corporations. Their paths finally crossed again in the 1990s, and they married in 1999.

By 2001, Ms. Kapor Klein was focusing more and more on issues of diversity, and the two former colleagues began to see the potential for combining their talents to make a serious difference in the world.

Mr. Kapor was “profoundly influenced” by his wife’s nonprofit advocacy work, he said, and he came to see his own experience in business as a platform for social change. “As I met the kids in the scholarship programs and education programs that Freada started, I understood that what they really needed was the same kind of opportunities that I had as a kid — to show what they could do.”

Technology still provides the foundation for their work. “Everything we work on is at the intersection of tech and social justice,” Ms. Kapor Klein said. “Some is in the nonprofit side and some is in the for-profit side. And it’s all about fairness and access and closing gaps — gaps of opportunity and gaps of outcome.” Their investments focus on underprivileged communities, especially communities of color.

One example of a startup that is closing the gaps is Lendup, a payday lending company. Unlike most payday (cash advance) lenders, which charge enormous interest rates, Lendup lowers its rate each time a loan is repaid, and helps people build a credit score.

Impact investment, as it’s called, is starting to catch on among foundations, universities and philanthropists, Mr. Kapor said. Kapor Capital is at the forefront of the movement. “I’d say we are still in the middle of the experiment, because it takes seven to 10 years really to get a full set of results,” he said. He hopes the company will inspire imitation.

The country’s steady decline in global education rankings forms the underpinning for the focus on technology. Ms. Kapor Klein said that by 2020 in the U.S. there will be one million unfilled technology-related jobs. “We don’t train enough, we don’t encourage enough kids to pursue computer science,” she said. She worried that the Googles, Facebooks and Twitters of tomorrow may be created elsewhere.

Their work is not just about doing what they believe is right, she said. “It’s an economic imperative for the country.”

Benjamin Jealous, former president of the NAACP and a Vineyard visitor, became a senior partner in Kapor Capital this year.

Ms. Kapor Klein said focusing on market-based solutions can give an edge over nonprofits, which often pursue the same goals but through legislative solutions. Part of the challenge, she said, is determining where for-profit dynamics are more effective, and where nonprofits still have the advantage. “When do people want to change laws, but when can we just work around them?” she said. “When do we not need to use a legislative strategy?”

The Kapors’ partnership with Benjamin Jealous is one example of the value of networking across sectors. As the nation’s largest civil rights organization, the NAACP shares many of the same goals as Kapor Capital.

During his five years as head of the NAACP, Mr. Jealous worked on critical issues such as payday lending practices and reforming the criminal justice system. “He completely transformed the organization,” Ms. Kapor Klein said. But in some areas, individual companies such as Lendup have been more successful.

For several years, the Kapors hosted gatherings at their home in Chilmark, where people could meet Mr. Jealous and learn about the work of the NAACP. When Mr. Jealous stepped down as president in 2013, he was looking for a new challenge and became intrigued by the market-based solutions that Kapor Capital was pursuing.

One area of overlap was an effort by the two groups to reduce the cost of phone calls from prison inmates, which can be as high as $4 per minute. Kapor Capital has been investing in Pigeonly, an online company that offers an alternative service at one tenth the cost and helps connect inmates to society.

Mr. Kapor suggested that Mr. Jealous join the firm as a venture partner, working one day a week to see if it was a good fit. “He got so engaged with this so quickly, he came back to us and made a counter proposal and said, ‘I want to do this full time,’” Mr. Kapor said.

When Mr. Jealous became a senior partner in Kapor Capital this year, he brought with him not only his expertise in social advocacy, but a wide range of government and business connections.

Many similar connections have been fostered on the Vineyard. This year, for example, the Kapors hosted an event for John Wilson, former director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities and president of Morehouse College. Last year the Kapors organized a tour of Silicon Valley for Mr. Wilson, as part of a larger effort to create pathways from Morehouse, a historically black college, to jobs in the tech industry.

Mr. Wilson was a classmate at Morehouse with filmmaker Spike Lee, who hosted the event this summer at his home in Oak Bluffs.

Ms. Kapor Klein said the biggest obstacle to impact investment is the deeply ingrained biases that in part shape the business world. She noted the

growing concern that the demographics within large technology companies do not represent the United States as a whole. She also cited research in neuroscience that reveals the hidden biases in how we make decisions. “We are more biased than we wish,” she said.

“Business can no longer be disconnected from the impacts that it’s having, whether it’s on the environment or people or unemployment,” she said. She said she believes awareness among businesses is growing, “but I think there is a lot of resistance.”

The long-term goal, said Mr. Kapor, is “to save capitalism from itself . . . from its own worst tendencies and excesses in promoting inequality . . . to have business more aligned with social goals and democratic values.” He doubted whether those goals were reachable, but he hopes to at least “nudge things in that direction.”

Ms. Kapor Klein joked that one long-term goal is retirement. “It’s why we are delighted that somebody like Ben Jealous, who is 41, is jumping in,” she said. She added that the company also employs people in their 20s and 30s. “So it’s really about turning over what we’ve learned and what we’ve done to the next generations.”

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »