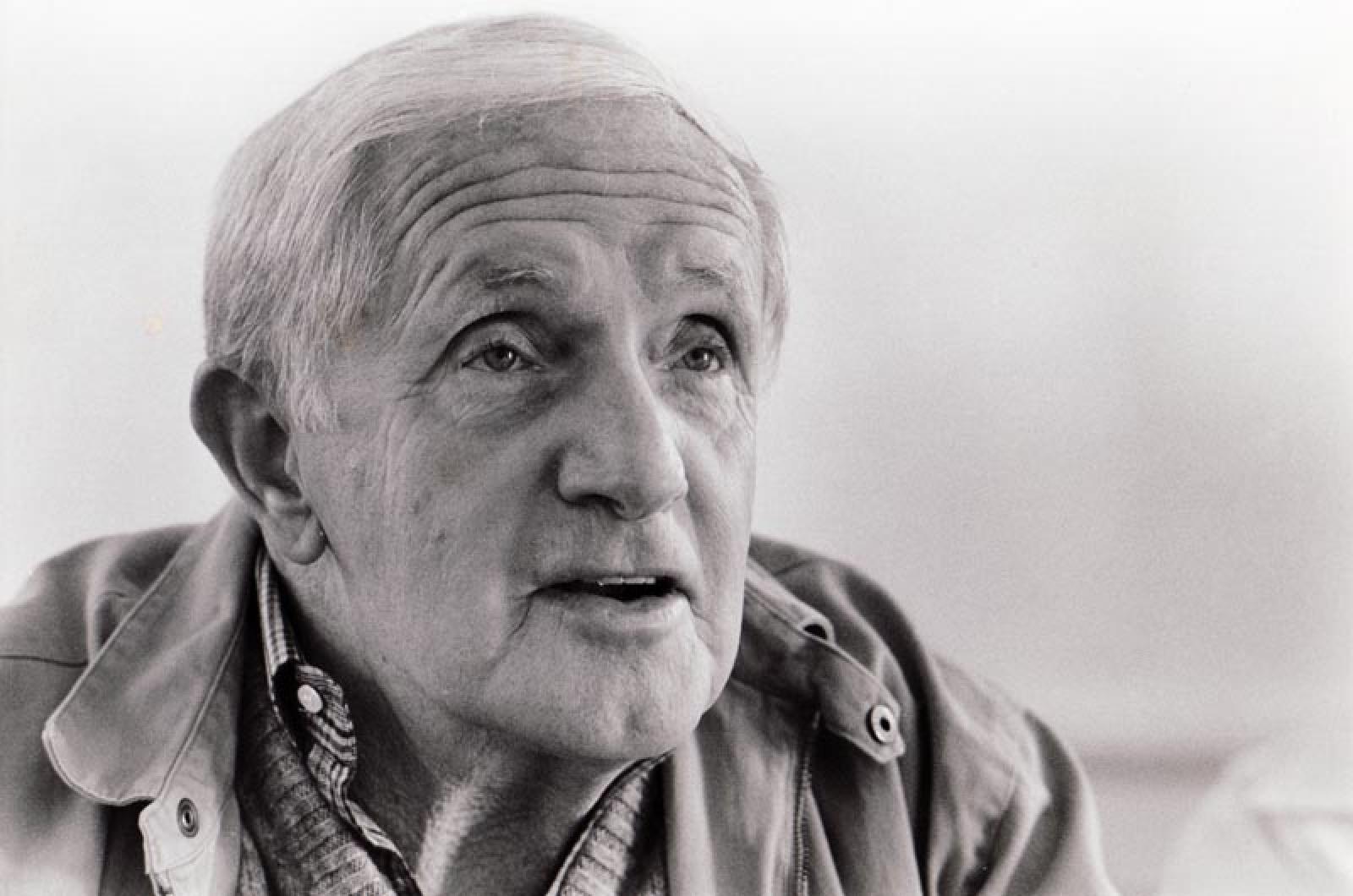

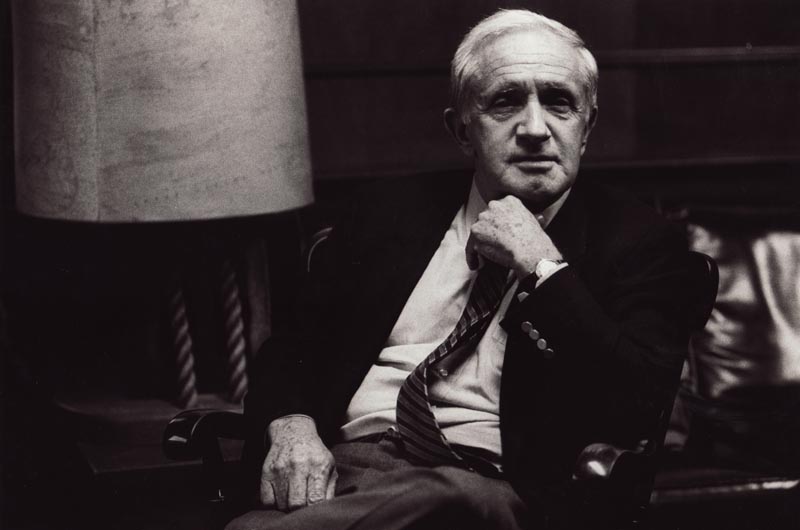

Robert J. Carroll, the prominent Edgartown businessman, conservationist, raconteur and longtime Vineyard power player who was sometimes a lightning rod for controversy, died on March 31 at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. He was 90.

A celebration of his life will be held at the Harbor View Hotel on Saturday, April 4, beginning at 4 p.m.

During his lifetime, Bob Carroll owned the Harbor View Hotel, the Kelley House, the Seafood Shanty and as founder of Carroll and Vincent Real Estate vast areas of prime Edgartown real estate. He was an Edgartown selectman for two decades, the town assessor, a Dukes County administrator, a board member of the Martha’s Vineyard National Bank and Camp Jabberwocky, a trustee of the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital and the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust, a founder of Martha’s Vineyard Community Services, the Martha’s Vineyard Boys & Girls Club and the Martha’s Vineyard Times. He established the Anchors senior center in Edgartown and led the purchase of Katama Farm by the town of Edgartown, which at the time was the largest conservation purchase in the history of the town. He sparred successfully with Sen. Edward Kennedy over the Nantucket Sound Islands conservation trust bill, and flew the senator off the Island in his private plane during the Chappaquiddick controversy.

If that sounds like enough for four lifetimes, it still doesn’t encompass all that Mr. Carroll accomplished over the years.

“I’m afraid we’ve lost a century of our cultural memory,” said Chris Scott, executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust. “A drive or a lunch with Bob was living history.”

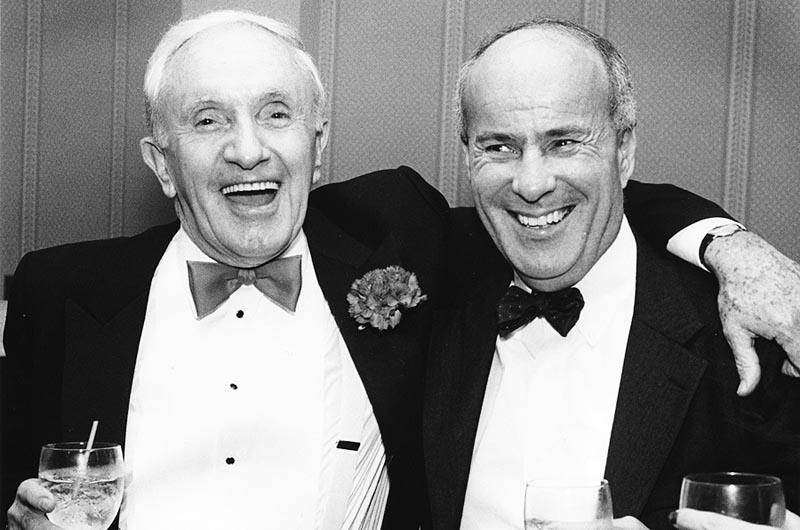

Ronald H. Rappaport, an Edgartown lawyer, concurred. “We’ve lost a great one,” he said. “Part of the unknown out there about Bob is that he was one of the most generous people on the Island. He would have given his last nickel to help someone in need.”

But lest it be thought that Mr. Carroll led merely a warm and fuzzy life, one only dedicated to the cause of helping others, here he is in his own words. “I haven’t been an angel,” he told the Gazette in one of his many interviews with the paper. “But I’ve had a good life.”

Bob Carroll was born to humble beginnings on August 15, 1924, “a poor ragamuffin” in his own words, on South Summer street in Edgartown, across the street from the Vineyard Gazette, which was the local poorhouse at the time. The Gazette, in particular its editor Henry Beetle Hough, would be the focus of numerous battles over the years.

In a 2004 interview with the Gazette, Mr. Carroll summed up what he thought of Mr. Hough like this: “An elitist snob in his own way, who did not think that the little ragamuffin from across the street should be associated with all the big shots out there.”

When asked in an interview with the Gazette how he was able to make the journey from ragamuffin to one of the wealthiest men on the Island, Mr. Carroll said that his life had changed when he decided to get sober at the age of 28, not long after he had returned from a stint in the Army. “When I got sober I started to get respect. I found if I could stay sober I could do almost anything I wanted to do,” he said.

Mr. Carroll began his climb to the top by leasing a coffee shop in Edgartown from its owner Edward W. (Peter) Vincent. “We had guys who would pay 10 cents for a cup of coffee and sit there all morning so no one else could get in,” Mr. Carroll recalled. “So I raised the price of coffee.” He then realized the town needed another restaurant, so in 1961 he bought the former Nevin Garage on Dock street and converted it to the Seafood Shanty.

Ronald (Puppy) Cavallo, now the owner of Soigne in Edgartown, was one of many who got their start at the Seafood Shanty.

“I spent 11 years with him at the Shanty starting at age 12,” Mr. Cavallo said. “He raised me as if I were family. He has always lovingly taken credit for anything and everything I have accomplished in life because he ‘taught me everything I know.’ Everything from cooking school to lovemaking techniques. Especially the latter, according to him.”

The Shanty led to the purchase of the Harbor View Hotel in 1965 and the Kelley House in 1973, both bought with his partner, state Sen. Allan F. Jones.

“The Harbor View when we bought it, the living room was full of old thunder jugs and piss pots, thunder jugs were the ones you sat on,” Mr. Carroll said. Mr. Carroll restored the Harbor View Hotel to its former and future glory, finally selling it and the Kelley House in 1986, but not before insuring that it would remain a part of his life forever, literally. As part of the sale agreement, Mr. Carroll was allowed to build himself a penthouse apartment to live in until his death.

Elizabeth Rothwell, the director of marketing at the Harbor View, referred to the man upstairs as “a dad, godfather, a mentor and the patriarch of the Harbor View. He knew everyone from the housekeepers to the engineers. And everyone loved him.”

Ms. Rothwell did admit to being “a bit shocked at the words he used. He had such an edgy sense of humor.”

Mr. Carroll also inadvertently helped out on occasion with a bit of business at the hotel, Ms. Rothwell said. “He was always taking guests to lunch, people he had just met.” Once, the sales team had brought in some important clients to woo, but then they couldn’t find them anywhere on the premises. It turns out Mr. Carroll had started a conversation with them and “they hopped into his car for a tour of the Island.” It ended up being a successful deal.

“I enjoyed having a little place to retreat to and being with Bob when it was so busy downstairs, like on July 4, ” Ms. Rothwell continued. “When we had a party, the Carroll family was always having a party upstairs.”

But the Harbor View property was also the scene of one of Mr. Carroll’s biggest battles, and his most direct adversary was Henry Beetle Hough. Mr. Carroll wanted to build two houses and a tennis court on the land between the hotel and the lighthouse. Mr. Hough and his backers argued that the land was an environmentally important and fragile wetland. The battle raged back and forth for nearly a decade. In a 1983 article in the Boston Globe, a reporter described the two adversaries this way: “Like two heavyweight boxers slugging it out, round after round, Robert J. Carroll and Henry Beetle Hough refuse to quit. And as they battle, the audience grows.”

In that same Globe article, Mr. Carroll goes on to say, “Do I really have an obligation to provide an unobstructed view of the lighthouse? Is there something wrong with a partial view?”

In the end, a compromise was formed and the wetlands remained intact, along with the unobstructed view that Mr. Carroll ended up enjoying from his penthouse apartment. For his part, Mr. Carroll received property that he would then bequeath to the Edgartown Council on Aging and become the Anchors.

Although he said otherwise, many viewed Mr. Carroll’s founding of the Martha’s Vineyard Times in 1984 with four other businessmen, as a direct result of his frequent battles with Mr. Hough.

“We’re not out to kill the Gazette,” Mr. Carroll said at the time. “I don’t intend to be the Rupert Murdoch of the newspaper business, either.”

The two adversaries were actually on the same side of one issue, although many years apart. In the 1940s Mr. Hough’s family purchased the land behind Main street in Edgartown to stop it from becoming a parking lot, and created the North Water Street Corporation. Many years later, Mr. Carroll acquired the stock to the corporation and engineered the gift of his stock to the Preservation Trust. The land is currently a park enclosed by Main street, North Water and North Summer streets, where there are two benches situated about 30 feet apart. The plaque on one bench reads Robert J. Carroll, President, North Water Street Corporation. The other bench plaque reads Henry Beetle Hough, Founder, North Water Street Corporation.

The benches were the idea of Chris Scott, who said with a laugh that he wanted to let Mr. Carroll know that the two men were forever linked together. “Mr. Carroll was not amused,” said Mr. Scott, again laughing.

If it seems odd that a hard-driving businessman would also be instrumental in conserving land, it was not a paradox for Mr. Carroll. He simply did what he thought was best for the Vineyard, and much of that had to do with wanting the Vineyard to be able to make its own decisions.

In the 1970s he led a heated and successful campaign against the Nantucket Sound Islands conservation trust bill proposed by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. The bill would have put the bulk of the decisions about the future of the Island in federal hands.

“I feel so strongly that the worst thing that politicians and political groups can do is underestimate the intelligence of the general public,” Mr. Carroll said.

Ironically, Mr. Carroll’s defeat of the bill led the way to the creation of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, an organization that was frequently the subject of his wrath.

And when Steven Spielberg was looking for someone to play a feisty selectman in Jaws, he didn’t have to look very far. Mr. Carroll not only scored the acting gig, he put up most of the cast and crew at the Kelley House — for a sizeable amount which helped him pay the mortgage at a crucial moment in the hotel’s history.

But perhaps Mr. Carroll’s most lasting legacy, according to all who spoke about him following his death, was how much he cared about the Island and the people who lived and visited here.

“He knew how to mix with the summer people and the Island people,” said Bridget Tobin, manager of the Steamship Authority’s Oak Bluffs terminal. Ms. Tobin first met Mr. Carroll over the phone, when she was a reservations operator, and that was enough to begin a friendship that lasted decades.

“You knew where you stood with him. And that’s what made him unique,” she said. “He taught me how to give back,” she added, before pausing to remember a comment he made recently while watching all the women disembark from the ferry. “Bridget, if my legs still worked, I’d be dangerous.”

Geno Courtney, another prominent Edgartown businessman, was reached sitting on a bench on Main street, a place where he and Mr. Carroll conducted many meetings. The two men had been friends since the early days of the Seafood Shanty, when Mr. Courtney was an apprentice barber in Oak Bluffs and would visit the restaurant after work for a drink. Mr. Carroll helped him get his start by opening the paper store in Main street in Edgartown, the first of what would be many properties Mr. Courtney currently owns.

“I lost a real good friend,” Mr. Courtney said. “And it’s a loss for the community.”

Mr. Carroll’s daughter, Sue Carroll, said that her father was “electrified by people. Of course, beautiful women, but all people. He connected with people in a way that was rare. Some that he had met for only 15 minutes.

“He loved life and that was a gift he gave to all of us,” she said.

Looking back at his own life, Mr. Carroll once summed it up like this: “Anything I owned, we had a good time. I didn’t believe in being miserable.”

He was married twice, first to Lucille G. Hillman, with whom he had four daughters, and later to Rebecca B. Welton, who both survive him.

He is also survived by his daughters: Sue Carroll and her husband Jerry Grant of Edgartown, Jane Joyce of Edgartown, Sarah Bray and her husband John of Arcade, N.Y., and Mary Ellen Goodsir and her husband Rohan of Reading; his grandchildren Rob Morrison of Edgartown, Alex Morrison and his wife Maggie of Edgartown, Adam, Patrick and James Joyce of Edgartown, Zachary Bray of Cambridge and Maggie Bray of Fort Riley, Kans., and a soon-to-be first great-grandchild of Fort Riley, Kans.

Comments (36)

Comments

Comment policy »