The discovery of hundreds of lone star tick larvae on Chappaquiddick this summer confirms that the southern species is breeding on the Vineyard.

Two weeks ago, Island biologist Richard Johnson surveyed about five acres at the northern tip of Chappaquiddick, where an unusual abundance of lone star ticks were reported earlier in the summer.

Within an hour on August 21, Mr. Johnson uncovered a nest with at least 100 larvae. At another site, he found larvae in five different locations. “I never expected to find this many lone star ticks in this many places,” he told the Gazette this week. “I thought they were still fairly unusual.”

He also found 250 adults and nymphs, using a flag to swipe along the edges of properties to pick up the ticks.

“It’s possible they have reached a critical mass and now we will see a major expansion in the next couple years,” Mr. Johnson said, although it was too soon to know how fast the ticks were spreading. Adults and nymphs have been observed on the Vineyard as far back as 1985, but the presence of larvae confirms they are not simply arriving on birds. But that also offers a degree of reassurance.

“To me it’s a more manageable problem than if birds were bringing in 10,000 of them every year, because we can’t stop birds,” Mr. Johnson said.

On Long Island, lone star ticks were first observed on Montauk in 1971, and on Fire Island in 1988. Cuttyhunk and Nashawena island are also thoroughly infested.

Daniel Gilrein, an entomologist with Cornell University, said the ticks on Long Island have benefited from the abundance of deer, which provide food and a way for the ticks to get around. Birds have almost certainly contributed to the problem, he added.

The flag-swiping technique can be used to estimate the population of ticks in a given area, but results vary according to location and time of year. Mr. Gilrein said that in some places in Long Island, a 30-second swipe might produce anywhere between zero to 100 lone star ticks.

Without annual data, it is impossible to know how fast the population is growing on the Vineyard, but Chappaquiddick resident Donald Greenstein, who drew attention to the problem this summer, said there were many more on his property than last year.

Lone star ticks carry several diseases, including tularemia, which is potentially deadly, and STARI (southern tick associated rash illness), which has symptoms similar to Lyme disease. Their bites are also painful, which can help distinguish them from other species.

The larvae are essentially smaller versions of the nymphs, with rounded bodies and a tan color. Adult females have a characteristic white dot on their backs. People may mistake the larvae for chiggers, which do not live in the region, although the bites of larvae also cause itching.

Mr. Gilrein pointed out that the larvae are not known to transmit any diseases. “The itching can be intense, and can be annoying, but as far as we know there is no disease threat,” he said.

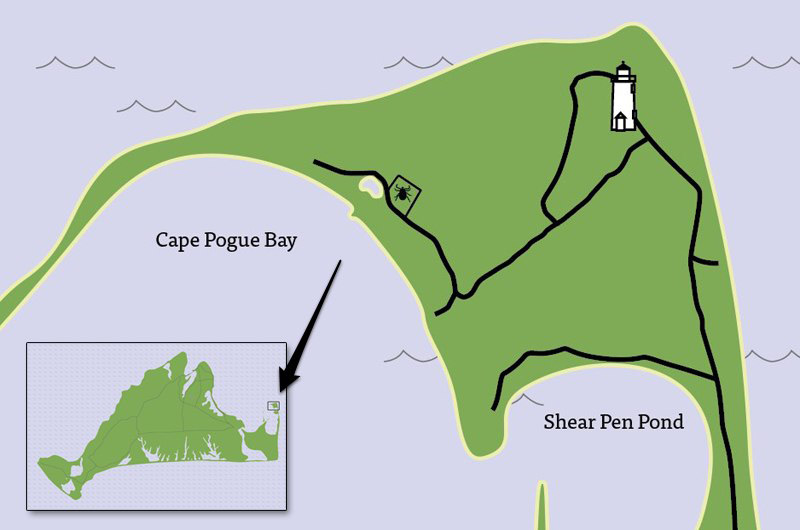

“Reliable sources” have reported lone star larvae on Cape Pogue and in Aquinnah, Mr. Johnson said, but he believed the two populations were disjunct, since he has only seen a few lone star ticks in Chilmark. He plans to survey a portion of Cape Pogue next week.

The only site on Chappaquiddick where Mr. Johnson did not find larvae in August had been sprayed with permethrin, a tick toxin, which he said was a good sign. But managing the population will be a major challenge.

The discovery of breeding comes just as funding for the Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative, an Islandwide program that began five years ago with a major grant from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, comes to an end.

Revenue from a new clinical research center in Vineyard Haven will help sustain the program, but Mr. Johnson will also be looking for grants and private funding sources. He also hopes to find some extra help as he works to evaluate the problem.

In some areas in the south, controlled burns have been effective, but they must be repeated for several years. Mr. Johnson believed that the scattered homes and relative isolation of Chappaquiddick would make burning there problematic.

Introducing more ground-feeding birds could be one approach, but while the birds eat the ticks, the ticks would also feed on the birds.

Some areas on Chappaquiddick that had been brush-cut — usually an effective management strategy — were home to a large number of larvae, suggesting that brush cutting would not be a effective solution.

“These appear to be more like dog ticks in that they can stand the heat, which makes sense because they are a southern tick,” Mr. Johnson said. Mr. Gilrein reported a similar situation on Long Island, where the ticks have rebounded even after stretches of extremely dry weather.

Perhaps the most progress on Long Island has been with four-posters, or feeding stations for deer that include permethrin-coated rollers that brush against the animals’ necks and ears. Mr. Gilrein noted a “dramatic decline” in areas where the devices were used and maintained.

A four-poster program on Chappaquidick was discontinued a few years ago, but Mr. Johnson has indicated a desire to start it up again.

Once he gets a lay of the land, Mr. Johnson will issue a report to local groups and homeowners. But the next step is to confirm the reports of lone star ticks on Cape Pogue, and in Aquinnah. “The sooner the better,” Mr. Johnson said. “I really don’t think we have a lot of time to waste on this.”

Anyone who encounters a lone star tick is encouraged to contact Mr. Johnson at rwilcoxjohnson@yahoo.com, or to file a report at mvboh.org.

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »