Attorneys in the Edgartown district court have found a loophole for challenging old drunken driving cases, all because a procedure to advise defendants of their rights may not have been followed by a former judge.

Judge Brian Rowe, who presided over the district court for 20 years, has been retired since 2005.

But a handful of defense attorneys who practice in the court have been successful in having old cases of operating under the influence (OUI) dismissed on behalf of their clients, amid claims that Judge Rowe did not properly carry out a procedure called colloquy. In at least two of those cases, the effect was to reduce criminal charges from a subsequent offense, which carries a harsher penalty, to a first offense. Although prosecutors have the option of bringing the cases again, in most cases the evidence has gone cold.

By definition a serious discussion, a colloquy in law is an exchange that is supposed to take place between a judge and a defendant when a guilty plea is entered. Among other things, the judge advises the defendant of his or her right to a trial and asks if the decision to enter a plea is being made with full knowledge of the consequences. The elements of colloquy are spelled out in the state’s rules of criminal procedure, and a box is checked on the docket to indicate that the colloquy occurred.

At least nine OUI cases have been or are in the process of being reexamined on the basis of Judge Rowe not administering the colloquy.

In one recent case, Vineyard defense attorney Jennifer Marcus filed a motion on behalf of her client asking that a 2002 drunken driving case be reopened because of a lack of colloquy. A motion for a new trial was granted in August of this year. Last month the case was dismissed by the commonwealth which was “unable to proceed,” according to court documents. As a result, Mrs. Marcus’s client had a drunken driving charge from June of this year amended from second to first offense.

The motion to reopen that case was accompanied by affidavits from Richard J. Piazza, a former prosecuting attorney with the Cape and Islands district attorney’s office who later did work as a defense attorney, and John Boyle, a longtime Edgartown attorney who handles criminal cases. Both said in sworn affidavits that they had never seen Judge Rowe conduct a proper colloquy.

Mr. Boyle said he had handled hundreds of cases before the judge, many of them drunken driving cases.

“I do not recall Judge Rowe ever giving a colloquy in operating under the influence cases,” Mr. Boyle said in part in the affidavit dated May 8.

In his affidavit Mr. Piazza concurred. “Not once did I ever see him conduct a full and proper colloquy of a defendant who tendered a plea,” he said. “His colloquy in operating under the influence cases consisted of the following questions that were addressed to me as the assistant district attorney: ‘Accident? Injury? Breathalyzer?’ I would answer accordingly, and Judge Rowe would sentence the defendant. On occasion, he would look at the defendant and ask him if he was guilty, and the defendant would reply ‘yes.’ ”

Reached by telephone at his home on Cape Cod this week, Judge Rowe declined to comment.

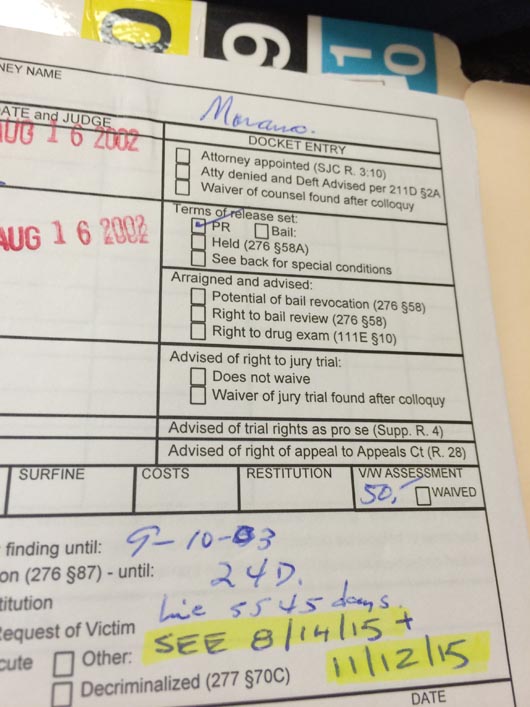

In October of this year, Edgartown attorney Charles Morano filed motions on behalf of a client in two prior OUI cases, one from 1986 and one from 1993. Mr. Morano asked that the dispositions be struck or set aside, claiming the plea was constitutionally invalid “because the record does not reflect a knowing and intelligent waiver of his constitutional rights.” In those cases, Mr. Morano, who formerly worked as a public defender from 1988 to 2014, filed his own affidavit. “I do not recall any instance during that time that the colloquy used by Judge Rowe in an operating under the influence case included advising the defendant of their right to trial, right to confront one’s accusers, or the privilege against self-incrimination,” he wrote.

In both cases, OUI charges against the defendant were dismissed by the commonwealth. As a result, a March 2105 charge of drunken driving, third offense, was amended to a first offense for Mr. Morano’s client.

Edgartown district court clerk magistrate Liza Williamson said this week that the colloquy issue dates to a time when practices and procedures in the district court were different from today.

“It was more informal, and our previous presiding justice apparently didn’t quite conform to what was required for a colloquy,” she said. “I’m not sure that anything was actually being violated. But this is what lawyers will do when they have a client with a subsequent offense [for OUI]. Then the DA’s office will have a case that is so old, they can’t go forward. The DA is put in a position where they need to dismiss the case. This has been going on for the last six years or so.”

She said all the cases have involved OUIs, although could not say precisely how many. “It’s a handful every year,” the clerk magistrate said.

Robert Moriarty, an attorney who does criminal defense work in the Edgartown district court, said this week that he has about seven cases that relate to the colloquy issue under Judge Rowe.

“I think the defense bar on the Vineyard and the Cape, and the judges on the Cape and the Vineyard know that Judge Rowe never gave a colloquy,” he said, noting that the colloquy often included three questions and the prosecutor sometimes was not asked to read the facts. “They have to hear a factual basis of the plea, ask if they are aware of the rights they are giving up, self-incrimination, defense, right to confront accusers. Every judge now, their colloquies are pretty much perfect but Judge Rowe . . . . didn’t for whatever reason,” Mr. Moriarty said. He continued:

“We have to do our job. The ramifications for a conviction for multiple-offense OUI can really be debilitating, not only in regard to loss of liberty, but license loss.” He said in some cases an eight-year loss of license can be reduced to a two-year license loss or less.

He also said there is no ongoing concern with colloquies in the district court. “All of the judges now are good,” Mr. Moriarty said. “And it should be that way. We wouldn’t be doing our jobs if we didn’t challenge this . . . . and we have to do it. Especially because it’s plain as day.”

Mrs. Marcus underscored the importance of the colloquy.

“When you plead guilty it needs to be knowing and intelligent and a voluntary plea,” she said. “It can’t just be because your lawyer told you to do it, or because you want to get a better deal . . . . it has to be done in a way that you put thought into it.”

Mrs. Williamson agreed, noting the sea change in the district court when it comes to rules and procedures.

“As time has gone on the rules have become more uniform and that’s a good thing,” she said. “The justices want to make sure that everybody is treated even-handedly in every court. When someone tenders a plea, they are waiving their right to a trial by either a judge or a jury — the colloquy is to make sure the person is making a knowing, intelligent and voluntary waiver of that right. That’s important for an obvious reason, because the right to a fair trial is one of the biggest rights we have.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »