A team of scientists and teachers last month deployed a small fleet of devices off Lucy Vincent Beach in the hope of tracking their journey to Narragansett Bay. Most of the 10 devices, known as ocean drifters, sailed past Noman’s Land and across Rhode Island Sound, confirming a link between Narragansett Bay and the waters south of the Vineyard.

Chris Kincaid, a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island, and his colleagues have been trying to understand circulation within Narragansett Bay, which lies about 25 miles west of Vineyard Sound. Among other things, they hope to reveal the origin of the currents, along with the critical nutrients they carry.

“We know that there is a lot of nitrogen in the bottom water of Rhode Island Sound,” Mr. Kincaid told the Gazette this week. But he said those nutrients are mostly trapped at the bottom by changes in the water density. “To get marine growth, you need nitrogen to be where the sunlight is, near the surface,” he said. “Our hypothesis is that there’s a lot of material that fuels the ecosystem that comes in this coastal current from the area of Martha’s Vineyard.”

The study has a number of applications, including the tracking of oil spills and floating garbage. But the ultimate goal is fisheries management. The study has received funding from Rhode Island Sea Grant, a partnership that includes URI and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which regulates offshore fisheries.

Researchers have long used drifters to track ocean currents, but efforts in the region have focused mostly on the Gulf of Maine and George’s Bank. The website for NERACOOS (Northeastern Association of Coastal Ocean Observing Systems) provides data for the drifter program run by NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

“We have had a few dozen drifters in that area in other years,” said James Manning, an oceanographer at the center who has worked extensively with ocean drifters in the region. “But this new batch is certainly going to help with the [modeling] of that current.” He added that more data throughout the year was needed to understand the averages.

The drifters deployed in May were unique in that they reached farther down than others (up to six metres), tapping into the subsurface flow, although still far above the bottom. Other instruments are sometimes tethered to the sea floor to measure the deeper currents. Those instruments have revealed a counterclockwise current in Rhode Island Sound, but did not answer the question of where the water originates.

About 50 schools in the region took part in building the drifters this year, including the ones that were deployed south of the Vineyard. Each of those cost about $300 and consisted of a long PVC pole topped with a cross-shaped sail and a GPS track pad.

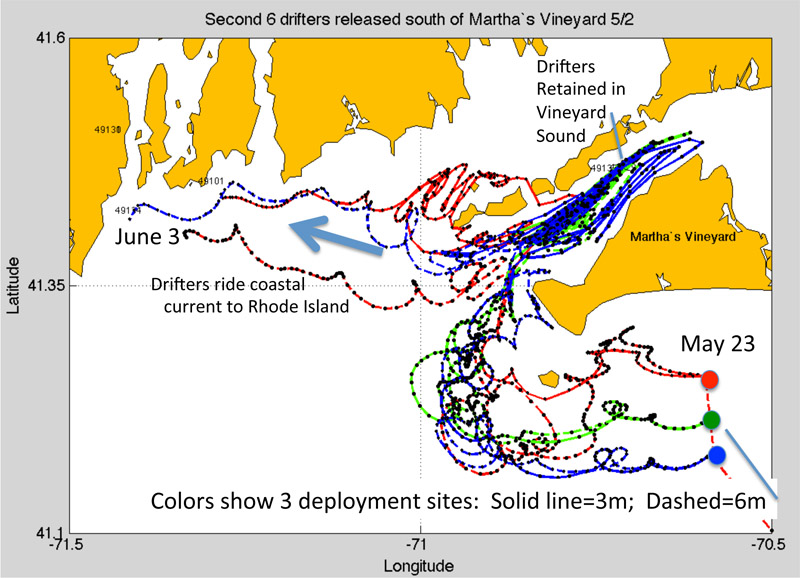

The first batch, deployed on May 19, took a wide swing around Noman’s Land but eventually headed toward Naragansett Bay. With calmer winds, the second batch on May 23 took a more inland track, into Vineyard Sound and then across Buzzards Bay.

Most of the drifters in the second batch also headed to Narragansett, although two got stuck in Vineyard Sound, where they floated back and forth with the tides for about two weeks. One of them finally broke free and traveled north around Oak Bluffs, turning south and roving back and forth in Nantucket Sound before rounding Chappaquiddick last week.

Mr. Manning, who supplied one of the drifters for the study, said the tides are so strong between Cuttyhunk and Woods Hole that they overpower the wind and other forces, in this case retaining the drifters. “They just go back and forth with the tides and it takes a very strong wind to kick them out of the oscillation,” he said.

All the drifters in the study are still functioning, said Mr. Kincaid, except for one that may have been struck by a ship and disappeared south of Narragansett. Another recently ran aground in Tisbury.

The unpredictability of the drifters, along with their relatively simple design, makes them an ideal learning tool for students, Mr. Kincaid said. Five schools in the region are involved in the URI study, including Pembroke High School in Massachusetts, with students and faculty following the progress online. In many cases, the schools build the drifters, with researchers providing the track pads and local fishermen ferrying them out to sea.

Mr. Kincaid said the URI study immediately drew dozens of questions following a group email this spring, and the technology allows people to keep track from afar. Each drifter path reveals the movement of the surface waters. And a combination of tides and the Coriolis effect (caused by the turning of the earth) creates a characteristic looping pattern.

Beginning in the fall, Mr. Manning plans to work with Vineyard teachers (including his niece Abby Smith, who will be teaching at the Oak Bluffs School) to bring the ocean drifters program to the Island. Teachers will deploy at least one device and track its progress with their students. Mr. Kincaid also hoped to get involved with Island schools, and thought the powerful tides in Vineyard Sound could even set the stage for a sort of drifter derby.

“Most of them probably won’t go around the Island, but some of them will,” he said of the drifters. “We have one that’s just about to complete the circuit.”

Looking ahead, he hopes to expand the study to track the waters around Martha’s Vineyard, which he believed originate around Georges Bank and the Nantucket Shoals, and possibly Massachusetts Bay. The next steps also include looking at the nutrients carried in the current. But for now, he hoped to retrieve the remaining drifters from Narragansett Bay and redeploy them next week in the same spots south of the Vineyard.

The study also had a personal twist for Mr. Kincaid, who spent a summer working on the Vineyard while he was a student at Wesleyan University. He recalled staying with Philip Wheaton, former president of Middlesex Community College in Connecticut, at his house at Lucy Vincent. Mr. Wheaton’s company one day looking out over the ocean inspired him to become a professor.

“When I put those drifters in, it was at night and we just pulled in to do it — and we were literally just off of Lucy Vincent Beach,” Mr. Kincaid said this week. “I really do feel like the course of my life was set based on that summer on Martha’s Vineyard.”

For more information on the drifters project, visit neracoos.org/drifters.

Comments

Comment policy »