In December of 1857, James Buchanan was in the White House and the Vineyard Gazette published a column about Frederick Douglass, who spoke at what had been the Congregational Church in Edgartown. Mr. Douglass presented his speech, The Unity of Man, to the church and town hall during his stay on the Vineyard.

More than 150 years later, Vineyarders gathered in the same historic building that is now the Federated Church to hear a reading of Frederick Douglass’s speech The Meaning of the Fourth of July to the Negro. Mr. Douglass had presented that speech to the Rochester Anti-Slavery and Sewing Society on July 5, 1852.

This was the third annual reading coordinated by Mary Jane Carpenter and the Friends of the Edgartown Library. The event started when Alice Delana of Chappaquiddick spoke to Virginia Munro at the library. She asked if Frederick Douglass had ever spoken on the Island. It turned out that he had.

“Virginia had the Gazette on microfilm,” said Mrs. Carpenter during a conversation before the reading. “After searching and searching she found proof in a column from December of 1857.”

Each year, Mrs. Carpenter selects several Island residents to read parts of the speech.

“Douglass had so many facets of his career, so I tried to pick people who matched one or two,” she said.

Born around 1818 as a slave, Douglass later escaped and lived as a free man. Over the course of his lifetime, he was an author, government official, journalist (most famously for William Lloyd Garrison’s the Liberator), abolitionist and preacher.

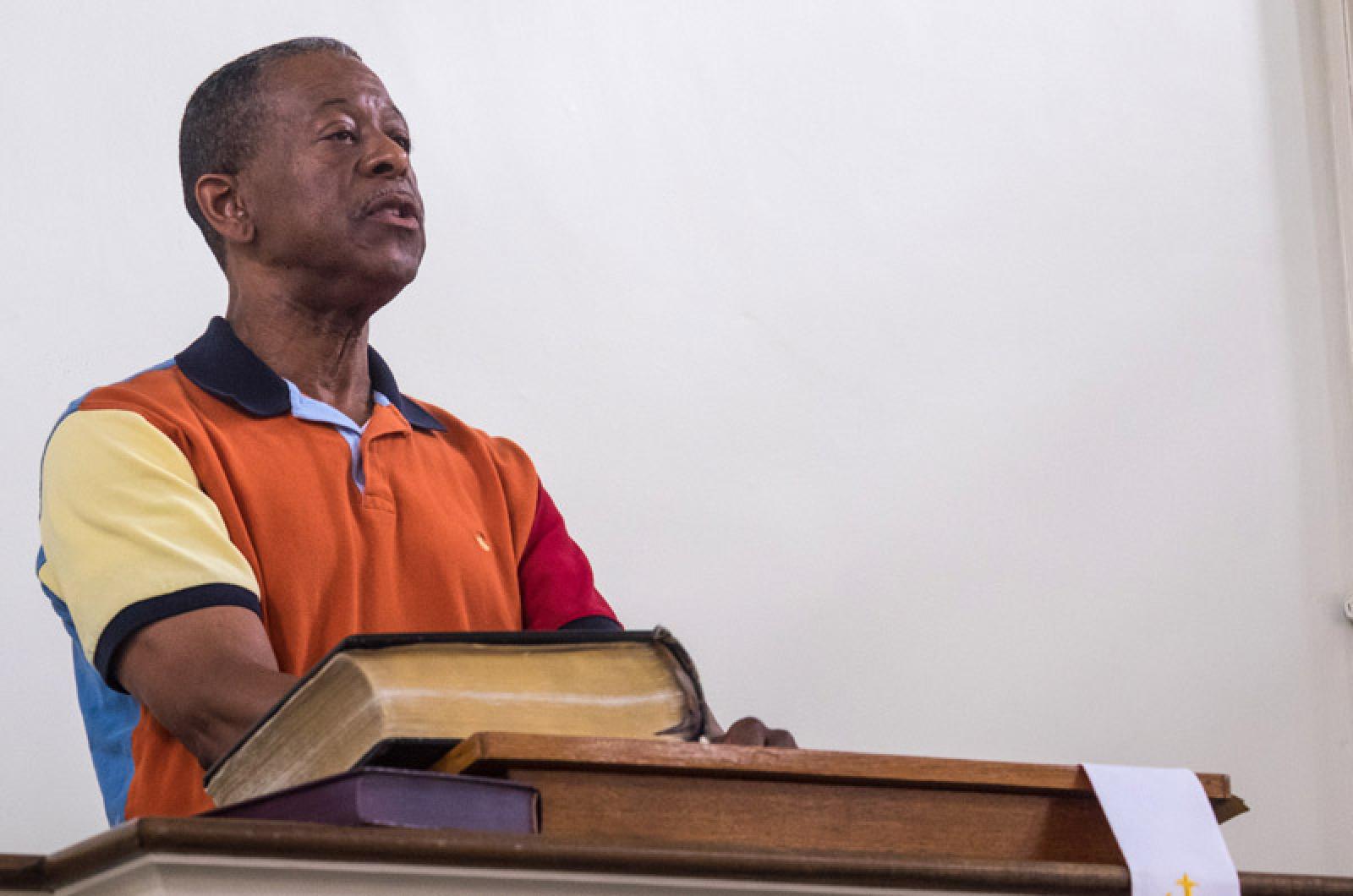

For this year’s 13 readers, Tom Dunlop and Jane Seagrave represented his newspaper work; Sharon Eckhardt, Cathlin Baker and Herbert Ward were of the church; former police officer and veteran Joe Carter for public service; and Margaret Chirgwin, graduate of the University of Edinburgh, stood for Douglass’s years in the U.K.

On Tuesday rain fell against the church windows as Douglass’s words rang loud and clear from the speakers at the pulpit. Before the reading, Ms. Carpenter explained the speech’s continued relevance.

“Mr. Douglass saw immediately that women issues and slavery of the 1800s were human issues,” she said. “He always said that if you see something wrong, you should educate. It doesn’t just apply to some people, it applies to us all.”

Douglass originally presented his speech to a group of white women, and he appealed directly to the country’s core values of freedom, Christianity and economic opportunity. He explained that July 4th for the slave was not a day of celebration but a reminder of their physical and mental enslavement.

Tom Dunlop spoke with a passion that Mr. Douglass would have admired as he read his part: “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

In 1852, Douglass spoke to a nation that had been independent for decades but had just passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it every U.S. citizen’s duty to return escaped slaves. The Supreme Court would pass the Dred Scott decision five years later and the country would go to war not long after. However, Douglass concluded his speech with hope.

E. St John Villard, a descendant of William Lloyd Garrison, read the ending of the speech: “But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind. Walled cities and empires have become unfashionable. The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city. Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth. Wind, steam, and lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together.”

Comments

Comment policy »