A Revive & Restore greater prairie chicken does its mating dance.

A cutting-edge effort to bring the heath hen back into existence is now the leading de-extinction project in the world, project leaders said this week. And while the prospect of a living heath hen is still years and several scientific steps away, the project has already put the Vineyard at the forefront of new technology that could have broad applications in wildlife conservation.

Ryan Phelan and Stewart Brand, the founders of Revive & Restore, an organization that aims to use genetics to rescue endangered species and revive extinct species, paid a brief visit to the Island this week to share news about rapid advancement in their work with the heath hen, a bird in the grouse family that went extinct on Martha’s Vineyard in 1932.

The most recent achievement is considered ground breaking: the potential culture of primordial germ cells from a greater prairie chicken. “This is the breakthrough. This is the news. This is potentially the game changer,” Mr. Brand said.

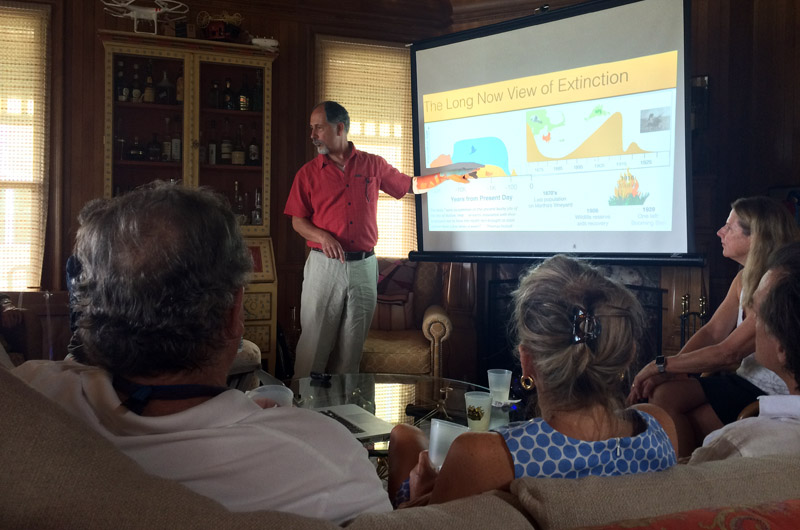

Beyond the intricacies of the science, the success so far with the heath hen project is also making a case for applying biotechnology to wildlife conservation, Ms. Phelan and Mr. Brand told a group of supporters who gathered Monday at the Oak Bluffs home of Peter and Gwen Norton.

“This isn’t a fringe thing in conservation,” Vineyard conservationist and project advisor Tom Chase said. “This is the beginning of a new way, this is bringing back iconic species that are representative of big healthy habitats . . . . it’s a movement.”

Once abundant on the East Coast, by the late 19th century the heath hen was found only on the Vineyard. Habitat loss, predation, hunting and wildfires contributed to the decline. By the late 1920s only one heath hen was left, a male called Booming Ben. He was last seen in 1932, and the species was declared extinct in 1933.

But the heath hen lives on, in a sense, through DNA found in museum specimens, opening the door to Revive & Restore’s work with genetic technology. The organization’s other leading de-extinction projects focus on the woolly mammoth and passenger pigeons. They are also working on genetic rescue projects for critically endangered species like the black-footed ferret.

With funding from several people with Vineyard ties, the first stage of the heath hen project, a complete genetic map of the bird and its closest relatives, got underway about two years ago. The work was completed ahead of schedule last summer and revealed new information: the heath hen was a unique species, not a subspecies of greater prairie chickens, and therefore a true candidate for de-extinction.

Then next goal, expected to take about two years, is to establish a viable primordial germ cell culture from greater prairie chicken cells. Using eggs from prairie chickens, scientists extracted the primordial germ cells (the cells that eventually become sperm or eggs), and attempted to grow them outside of the animal. If this can be done, the door is open to editing the cells.

Revive & Restore is working with Grouse Park, a breeding facility in Idaho, where a flock of 10 greater prairie chickens was established last fall.

During the presentation Monday, Ms. Phelan and Mr. Brand showed a short video of one male greater prairie chicken in his breeding display, called lekking. As summer sounds drifted in from Ocean Park, the room filled with hooting, whistling and squawking as the bird danced and stomped, his bright yellow neck glands inflating and deflating.

“That’s what heath hens looked like and sounded like,” Mr. Brand said.

The spring breeding season led to 72 eggs, which were shipped down to Crystal Bioscience, a company in the Bay Area. Scientists extracted primordial DNA cells from the fertile eggs to try to grow them in the lab.

The process requires the right “broth,” or media to grow it in. The first attempt was a bust.

But the second attempt appears more successful. As of late June, there were five promising potential cultures. Tests will confirm whether primordial germ cells are truly growing, but Mr. Brand and Ms. Phelan are optimistic.

“Ahead of the game,” Mr. Brand told the Gazette in an interview Monday. “Yee-haw.”

If tests are negative, work will begin again on perfecting the process. If the cells are confirmed, it would be a breakthrough, and on to the next step: germ line transmission. This could eventually involve editing cells to create, say, a chicken with the gonads of a prairie chicken. If the chicken mates with a prairie chicken, their offspring should be prairie chickens. Theoretically, this could eventually work to create heath hens as well.

The scientists are pinning their hopes on using domestic chickens as the host bird, because of the abundance of eggs produced. If the chicken doesn’t work, the greater prairie chicken is a fine candidate, they said, but they breed only once a year.

As for funding, the second phase of the project was estimated at $180,000; three-quarters of that has been raised so far. The project will likely cost around $1 million over the next three to 10 years, Ms. Phelan said. Revive & Restore hopes to eventually partner with a science foundation or other organization for funding.

Work also continues on the woolly mammoth and passenger pigeon projects, among others. Ms. Phelan said scientists involved in the various projects have regular phone conferences to share progress and best practices.

So far, the heath hen project leads the pack. Each step along the way has been proof of concept that de-extinction can work, Ms. Phelan said.

The project has benefitted from its close relation to the domestic chicken, one of the most familiar and well-studied avian species, and its connection to Martha’s Vineyard.

“De-extinction has been hard to fund in other cases, with the great auk and the woolly mammoth,” Mr. Brand said. “Thanks to Martha’s Vineyard there has been specific money for the heath hen.”

But there are misgivings among some scientists and conservationists, who have raised ecological and ethical concerns about de-extinction.

Mr. Brand and Ms. Phelan say they only want to proceed if there is interest and buy-in from the public, noting that the work is a natural extension of using genetics for medicine and agriculture.

In another project that could affect the Vineyard, scientists are also looking into genetically engineering white-footed mice to be resistant to Lyme disease, which could help control spread of the disease to humans. As for the heath hen project, Mr. Chase said the main question he gets is “why?’ He said the project is not just about the heath hen, but about restoring the bird’s preferred habitat, open grasslands with low shrubs like huckleberry and blueberry.

“My message is, it isn’t about this bird, it’s about the habitat and the whole sequence of things,” Mr. Chase said. “And it isn’t about the Vineyard, it’s about the whole Eastern Seaboard.”

For hundreds of years Native Americans managed the Vineyard landscape with fire, he said, which controlled overgrowth and reduced the risk of forest fires, both factors that benefitted the heath hens.

When colonists arrived on the Vineyard, fire suppression largely ceased but agriculture was widespread, and open grazing land was also a boon to the birds. When farming later declined and forests began to regrow, the heath hen habitat started to disappear.

Other factors chipped away at the heath hen population — hunting, cats, invasive species, even harvesting for heath hen pelts, which were sold on the black market — but Mr. Chase said habitat loss was the most critical part. Open grasslands exist on the Vineyard now in fragments, like at the Katama airfield and parts of the state forest, he said. But these areas are too small to sustain a heath hen population, which would need about 5,500 acres.

Restoring grasslands for heath hens could bring back other species that have disappeared from the Vineyard in his lifetime, Mr. Chase said, like short-earned owls, American kestrels and the regal fritillary, a striking orange butterfly.

In the next months, and years, most of the critical work will likely take place in laboratories and in breeding pens in Idaho. If the science keeps pace and funding comes through, Ms. Phelan estimated that genetic editing for heath hens could start in two to three years. Beyond that point there would be discussions about captive breeding facilities at locations to be determined, and more talk about creating habitat and seeing what works.

And perhaps beyond that, heath hens like the one on the screen in the Nortons’ living room could perform their mating dance on the Vineyard or elsewhere.

Taking a longer view, Mr. Brand looked ahead to 2032, the centennial of the heath hen’s extinction. By then the heath hen could be back, he said, its absence a relative blip in the long view of time. “And then they’re around for another two million years, during which time people would say, this bird, oddly enough it was extinct for 100 years. And now it’s back.”

Comments (12)

Comments

Comment policy »