As the Island prepared for Tropical Storm Hermine on Sunday, a black racer snake named Miss Audrey was seeking shelter of her own, but not from the storm.

BiodiversityWorks in Vineyard Haven has been tracking the snake since July as part of a larger study to collect baseline data on the elusive Island species that has declined in the last 20 years.

Under a clear blue sky, Liz Baldwin of BiodiversityWorks, along with volunteer Isobel Flake, pulled off the road in the Long Point Wildlife Refuge in Edgartown, where the snake had been captured and then released with a radio transmitter in July.

Ms. Flake unfolded the arms of a metal antenna and attached it to a small tracking device that immediately began beeping: a lucky start to the afternoon.

The only sign of the impending storm was a steady northeast wind that rustled the oaks as the team set out through knee-high huckleberry and blueberry bushes in the direction of the snake.

After a while, the beeping suddenly grew louder and Ms. Flake saw the flash of a black tail, followed by the rustling of grass and bushes as the snake darted away. The beeping quickly faded, but the search continued.

“That was really fast,” said Ms. Flake, who had yet to see the snake in person.

The study began in 2014 with funding from the Edey Foundation, and a goal of gathering historical information and reports of recent sightings on the Island. Most sightings have been reported around Long Point and Oyster Watcha Pond in Edgartown, with some as far west as Aquinnah. So far, no other black racers have been spotted during the tracking portion of the study this summer.

As with many Island snake species, little is known about black racers (Coluber constrictor), although they have been documented here at least as far back as the early 1800s. “People used to see them all the time,” Ms. Baldwin said. “You’d pull up a board and there would be a black racer under it. In the last 20 years they’ve really declined.” Most fatalities are likely due to vehicles, she said, in part because snakes often lie on roads to regulate their body temperature.

“Think about what the landscape looked like 20 years ago, when there weren’t all these roads and houses,” she said. “Now everything has been fragmented.” She believed it was possible that the use of rat poison has also contributed to the decline, as is likely the case with some raptors.

New England states have taken steps to protect the species, including by adding it to their State Wildlife Action Plans, although the data is still sparse. Biologists in Maine and New Hampshire have already completed radio telemetry studies. BiodiversityWorks felt it was important to contribute information from an Island, where the species may behave differently than on the mainland.

Researchers last year laid wooden boards around in places to lure the snakes, but the only black racer they found was too small for the study. This year they teamed up with The Trustees of Reservations, which manages the Long Point Wildlife Refuge, to set traps on their property. Silt fencing guides the snakes toward a chamber they can enter through highway cones. (Snakes tend to move along a barrier, rather than around it, so no bait was needed.)

Volunteer Audrey van der Krogt, for whom the snake is named, discovered her in one of the two traps in July. West Tisbury veterinarian Michelle Jasny anesthetized the snake and surgically implanted the transmitter, which will last for about a year.

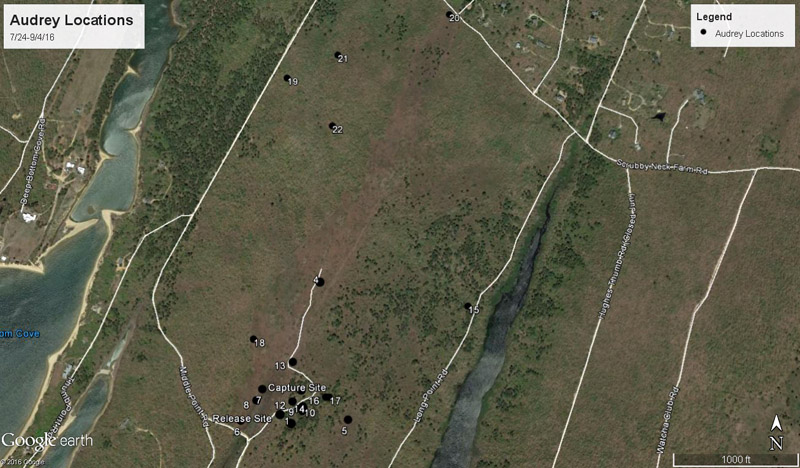

“Right now this is just a little pilot study,” Ms. Baldwin said on Sunday. “Where is she going, how long does it take to track, what are her movements like, and looking at what habitat she is using, how many roads she’s crossing. Just getting some general information.”

Three times a week, researchers track Miss Audrey’s location and make a note of her surroundings. For the first week or so, she stayed in the area where she was captured, shedding her skin and hiding underground. Ms. Baldwin said the most valuable data gathered so far may be the presence of multiple black racers in the study area, which covers about 250 acres and offers ideal habitat, with early-successional oak and pitch pine forest and shrubby undergrowth. Another black racer was caught in June but escaped.

After another few minutes on Sunday, the beeping grew louder and voices dropped to a whisper. The signal coalesced around a single white oak, swaying gently in the breeze. An opening at the bottom led upwards into the trunk. Ms. Baldwin unplugged the antenna and used the tracking device and wire like a stethoscope, listening to the tree and finally pointing to a spot about shoulder-level where the snake was hiding inside the trunk.

The species is known to climb trees, but this was the first time Ms. Baldwin had observed that type of behavior during the study. After taking note of the surroundings and setting up a motion-sensitive camera at the base of the tree, the team gathered up its equipment and called it a day.

Back at the truck, Ms. Baldwin listed a number of things people can do to protect black racers. She discouraged the use of bird netting on gardens, which may cause strangulation, and the use of sticky traps for rodents, since they may catch snakes as well. She also advocated for less habitat fragmentation and fewer roads (especially paved roads, which get warmer and attract more snakes). But she said the best way to protect the species is by raising awareness.

“I think the biggest thing is appreciating the value of snakes in the ecosystem,” she said. “Especially the black racer, where they are eating small rodents and white-footed mice, which carry Lyme disease. Maybe they are not making a huge impact on the white-footed mouse population, but they are playing this role in reducing the rodent population.”

Eventually, BiodiversityWorks hopes to track Miss Audrey to her winter hibernaculum — likely an underground burrow where the temperature is stable and not too cold — and find other snakes they can track next year, although that would depend on continued funding.

“There’s probably multiple racers in this area,” Ms. Baldwin said. “How many, we don’t know, but maybe they are all going to the same hibernaculum. So that would be really cool to find out.”

To report a snake sighting on the Island, go to biodiversityworksmv.org.

Comments

Comment policy »