Interest in offshore wind energy in the Northeast continues, with two companies vying for the remaining leases in the Massachusetts wind energy area south of the Vineyard.

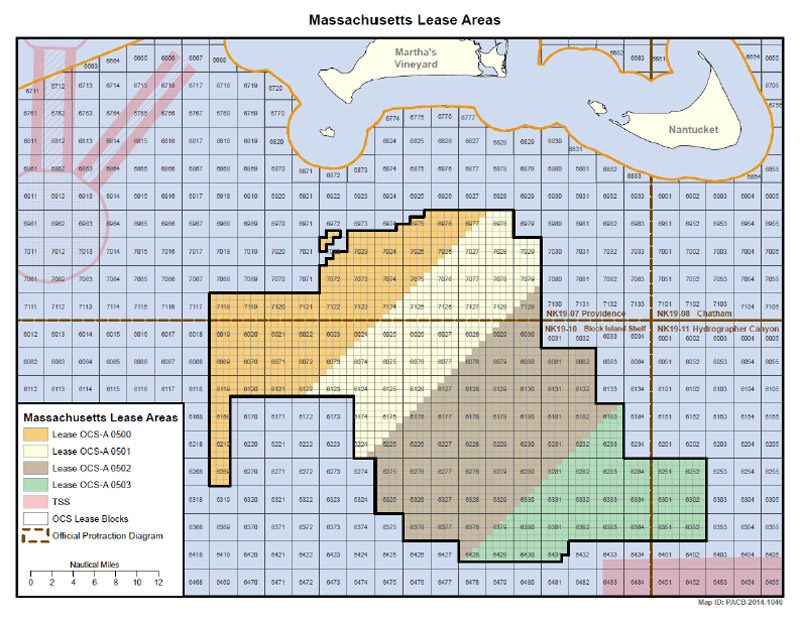

Statoil Wind US and PNE Wind USA have filed competing requests with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to lease two areas in the Massachusetts wind energy area south of the Vineyard, which had no takers in a federal auction two years ago.

The requests have triggered a new public bidding process, although BOEM has not yet announced a timeframe going forward. And it remains unclear how the federal program will fare under President Trump, who has begun to reverse many of his predecessor’s alternative energy policies.

Each company would pay about $1.17 million per year for the two areas, which cover 388,569 acres beginning about 20 miles south of the Vineyard. The lease term is 31 years, including a one-year preliminary term, five years for site assessment, and 25 years for operation.

Statoil proposes at least one new wind farm with between 400 and 600 megawatts of capacity. In its formal request in December, the company noted a gross potential of between three and 15 gigawatts of capacity in the two areas.

PNE plans to build two 400-megawatt wind farms — one in each area — with a total of between 80 and 100 bottom-fixed turbines. That works out to between eight and 10 megawatts per turbine, although the company notes technological advancements that have doubled the size of turbines in the last decade. PNE’s application was also submitted in December.

The Norwegian oil and gas giant Statoil ASA operates in 37 countries and is considered a world leader in deepwater wind development. PNE Wind USA is a subsidiary of the German company PNE Wind AG, which operates in more then 14 countries.

The two remaining areas off the Vineyard include deeper water than the areas to the west, with some portions exceeding 60 meters, and are farther from the mainland. But they have also been shown to have higher average wind speeds (up to 9.4 meters per second at height), which could help offset the cost of development.

Both companies plan to attach the turbines directly to the sea floor, although PNE notes in its applications that the design would depend largely on water depth and other physical conditions, as well as factors in the supply chain.

Vineyard Power, the Island energy cooperative, has partnered with the Danish company OffshoreMW to develop an adjacent area to the east, with Danish company Dong Energy developing a site just west of that. Both projects are in the permitting phase.

All four of the lease areas include sensitive marine habitat, including that of endangered right whales and endangered sea turtles. A federal environmental assessment completed in 2014 concluded that wind energy development would have no significant impact in the area.

Both companies in their applications indicate a desire to minimize effects on the environment, with Statoil calling “health, safety and environment” its top priority. PNE notes alternatives in the 2014 assessment, stating that some portions of the lease areas could remain undeveloped to protect right whales.

“The presence of NARW [north-Atlantic right whales] and other species raises the question going forward as to the amount of total usable area,” PNE states in its applications, although it also notes the lengthy review process in recent years.

The federal government has awarded 14 leases for wind farm projects along the east coast since 2010, although some have expired or been relinquished. Statoil owns interest in 10 offshore wind projects in the U.S., and recently paid $42.5 million for development rights to 79,350 acres in federal waters off New York.

In December, Deepwater Wind, headquartered in Providence, R.I., activated the country’s first offshore wind farm, with five turbines now producing about 30 megawatts in federal waters off Block Island.

PNE has said it hopes the Block Island Wind Farm marks a turning point for offshore wind development in the U.S. Other hopeful signs for developers include a new law that requires utilities in Massachusetts to purchase at least 1,600 megawatts of offshore wind energy by 2027, and the planned closure of both the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant in Plymouth in 2019, and the coal-powered Brayton Point plant in Somerset in May.

The Obama administration had outlined a strategy for 86,000 megawatts in private offshore wind development by 2050. But President Trump has called wind power ugly and harmful to birds. This week, Mr. Trump signed an executive order aimed at dismantling a number of climate-change policies enacted under Mr. Obama, including the Clean Power Plan, which focuses largely on boosting renewable energy production.

A study by the transmission company ISO New England found that adding 1,000 megawatts of offshore wind capacity in the region would save between 1,518 and 2,132 kilotons of carbon dioxide per year.

The leasing process requires public notice to potential developers, and to the public at large. The winning bidder would conduct site assessments over five years, with BOEM conducting environmental and technical review. Eventually, the company would submit a construction and operation plan for BOEM approval.

PNE anticipates construction beginning in 2025. Statoil does not include a timeframe in its proposal, although both companies have noted that energy contracts under the new state law must be in place by 2027.

Comments

Comment policy »