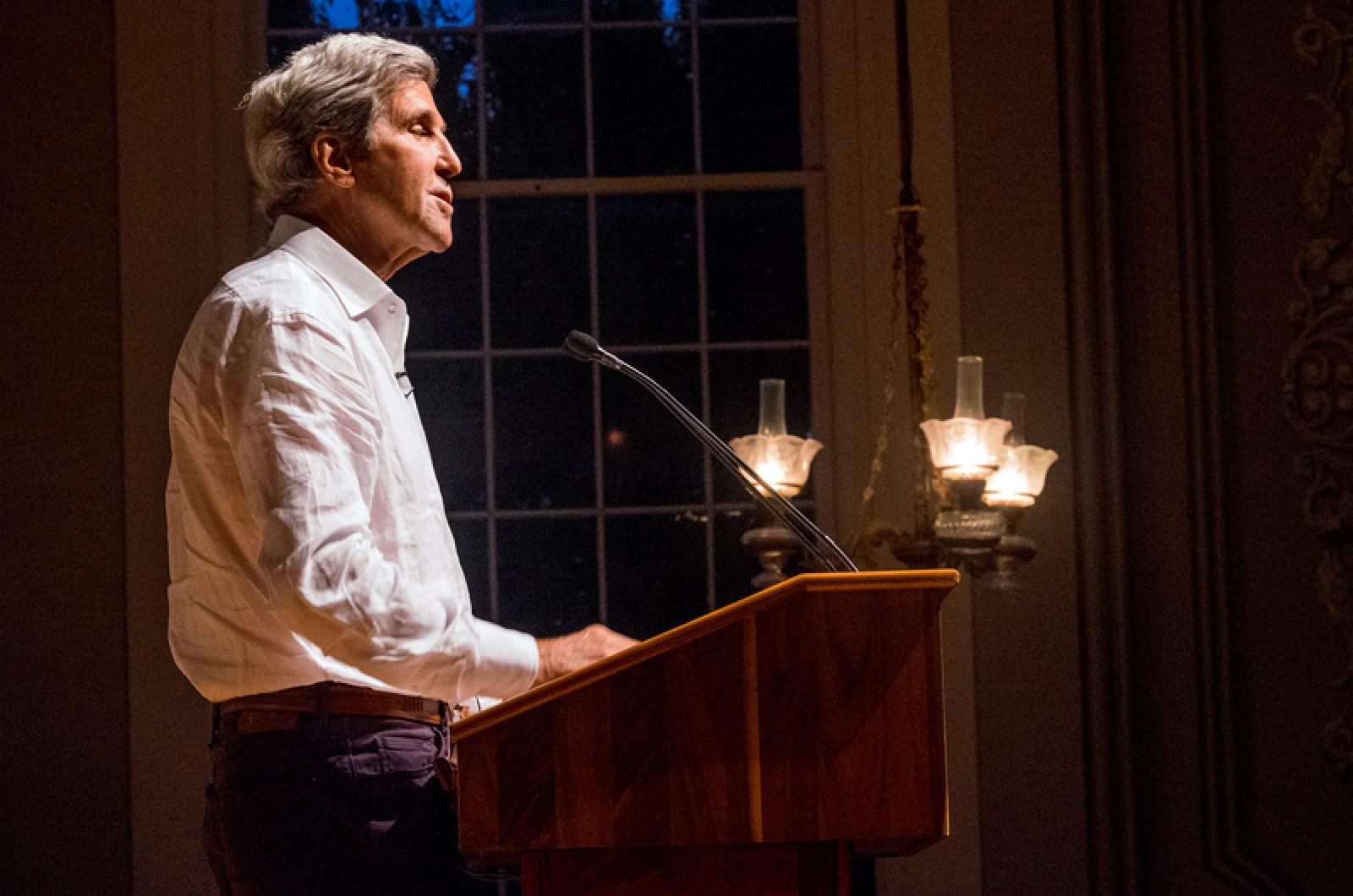

What follows is an edited transcript of John Kerry's talk on July 27 at the Old Whaling Church.

Everybody here knows that the great American novelist Thomas Wolfe wrote prophetically that you can’t go home. And I’ve experienced a few moments where perhaps that’s proven true. But I want you to know that after four years on the road and a million and a half miles as Secretary of State, I can tell you right here—Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts—it is really good to be home.

I think it’s incontrovertible that the last 70 years have brought a remarkable level of prosperity, peace, nation-states not fundamentally going after each other the way they did for most of the 20th century, far fewer people dying than were dying at any time in the course of the 20th century.

Think about it. What we built, what our parents, what those who committed to the postwar structure, what they achieved is nothing less than extraordinary. And part of the problem today is that millions of Americans have no sense of the fragility of peace, of what happens in the absence of it, of those ingredients that contributed to the horror of the Holocaust and of 30 million Russians dying.

Together what we built helped defeat the Soviet Union. It rebuilt a free Europe, a second time. It welcomed the former Soviet states into the warm embrace of the continent. It responded to Bosnia and Kosovo, ultimately bringing resolution to new and perilous threats to life and to dignity.

In fact, during the journey of the last 70 plus years, we have seen the most sustained period of economic growth in human history. We’ve crafted new principles for governing relations among states and, until recently, we adhered to those principles with a remarkable sense of direction and purpose and with a connection to the values in which this great nation of ours was founded. And we all knew why these institutions and these principles were so important, because our parents were the greatest generation—families that had seen World War II, and understood what happens in our own neighborhoods when that order breaks down.

Like most in my generation, I developed a very early, visceral understanding of how close the world came to total chaos and destruction, and how essential allies and alliances, dedicated to order and to openness and to democracy and to decency, how important they really are. Not just to avoiding that tipping point, but to putting the world together, making sure that never again would we come close to some intolerable alternative. That has been a driving organizational force of global politics since World War II. We can’t just rely on the greatest generation and its legacy - everybody has an obligation to try to be the greatest generation.

The irony is that perhaps in part because our global system has been effective in fostering an enduring peace, a whole bunch of folks, if they were ever connected to it, have lost the sense of tragic awareness about the fragility of peace. In Europe and America and everywhere it seems there is a growing constituency for a kind of neo-populism that argues that the very alliances and organizations that protect us are actually part of the problem. Logic is being absolutely turned and twisted on its head. Many people are again drawn to the fool’s gold that tempts people with the promise that if we just retreat within our borders, loosen our ties to each other, and to the rest of the world, we can actually somehow do better going it alone and focusing on our own societies.

History tells us starkly that what I just described is not how you make America great. That is how you make America cut off, alone, and vulnerable to threats that have no respect for borders in the 21st century. And that is how you leave our allies and our friends, who count on our consistency and our strength of character, who count on leadership from the United States.

We are leaving people reeling in a dangerous swirl of uncertainty and doubt, and none of this makes us any stronger or safer. So what can we do? Well the starting point to turn things around is to understand and acknowledge that the deep frustration that so many of our fellow citizens feel is not unwarranted, not in the least. People are fed up and alarmed by corruption, I’m talking globally. By inequality, by terrorism in the streets, and the consequences of technological change have added to people’s unease despite the associated benefits that technology can bring.

The catastrophe in Syria and the global refugee crisis raised questions about the collective ability of countries, of the international community, to be able to respond. People fear that fierce global competition is going to drive them from the workplace and that their schools and communities are going to be transformed beyond recognition into the worse by migrants and refugees. And this churning has made the job of shaping world events far more complicated than I’ve ever experienced it, made it harder for governments to be able to deliver their citizens the most basic functions, from enforcing the rule of law to providing security to enabling citizens to pursue their dreams with hope and with optimism.

And this is true in countries all around the world. Remember that the Arab spring began because a fruit vendor in Tunisia was tired of being slapped around by the cops. It had nothing to do with jihadism or religion or extremism. It was corruption.

The biggest difference that we can make in restoring trust or faith in governance is to make government do things that actually make a positive difference in people’s lives. The first thing that we have to do is a better job of organizing the global response to defeat the forces that seek to impose a radical violent extremism on people everywhere. Confronting Daesh on the battlefield in Syria and Iraq is critical. But there will be different kinds of Daeshes that reemerge if we don’t do a whole bunch of other things.

As Henry David Thoreau said, there are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to only one who is striking at the root. So we have to strike more effectively at the root causes of violent extremism. First you have to understand why people are driven to this. Some of these folks are without question tribal or sectarian allegiances that are reflected. Others are in response to oppression.

Assad and Daesh feed off each other with the cruelty of each driving desperate people into the poisonous embrace of the other. And when people, particularly young people, have no faith in legitimate authority, when there are no outlets for people to express their concerns. frustration festers. And no one knows that better than violent extremist groups which regularly use indignity and marginalization and inequality and corruption as recruitment tools.

At the same time we’re seeing a wave of technological transformation taking place in every aspect of our societies. And that is the second generational challenge that we face. In country after country, ideas are moving faster, people are moving faster. The marketplace is moving faster. And the only thing that isn’t coming at us faster is the ability of governance worldwide to respond.

But there’s something else happening. Many people who were hurt in the 2008 economic implosion, particularly here in our country, are still feeling the pain. Here in the United States, your average family suddenly found their house worth half its value while being stuck with 100 per cent of a whopping mortgage. That is a pretty simple recipe for a lot of anger. That and the fact that despite working harder, in many cases two or three jobs, people still don’t get ahead.

Trade has become the target of all of this, but here again politicians are exploiting rather than leading because it’s technology, not trade that is the principle reason we have lost 85 percent of the 5.6 million jobs we lost in the first ten years of this century.

So the shared task that our governments face is not to make false promises that they can’t possibly honor and to find new ways to unleash the next wave of innovation and jobs that will lift all of our people up together. That means demonstrating a laser-like commitment to economic growth that benefits the many not just the few, to growth that is fostered by early-childhood education, by life-long learning, by apprenticeship programs. It means making it easier for entrepreneurs to turn their good ideas into new companies that are going to pick up the employment slack as older industries phase out. It means adjusting to the so-called gig economy by taking advantage of its flexibility with allowing it to undercut the benefits.

It also means we have to make trade a priority and I don’t mean to weaken standards or undo regulations. On the contrary, we have to lift up environmental and labor standards in all of our nations and showcase the dynamism that our model of democracy and free markets offers when it comes to economic standards.

Now there are no instant fixes to the economic challenge we face but if you look back through history you will see that adjusting to technology and to the shifts of how people earn a living has been a constant fact of life in our country. We humans are a remarkably resilient species

In the beginning of the 20th century, 50 per cent of America worked in agriculture. You know what it is today? Two per cent. But we’re still growing the economy, people are still working. What we haven’t worked out is how to value the work that we do appropriately. This task is enormously important and we have to remember that economic policy is foreign policy in today’s world and foreign policy is economic policy.

Now the challenge of this broad economic effort is staggering because we have to provide something like 60 million new jobs in the next decade to the states in the Middle East, the Gulf, just to keep pace with the number of young people entering the workforce. And that is not a task that is going to fall on their governments alone. That’s why we have to be engaged. That’s why we have to lead. It matters for all of us.

When we were emerging from the darkness of World War II, America switched on a light called the Marshall Plan. Between 1948 and 1951, the United States invested between $12 and $13 billion in the recovery of Europe.

We need a new plan for the 21st century. A plan that starts by recognizing the reality that no government in the world has the ability to move fast enough to tackle this on its own. One that is focused on not bypassing developing countries. I say this because there is no other way to achieve peace in the world.

What I’m talking about is the largest public-private partnership the planet’s ever seen, working with the World Bank, with the other international financial institutions including the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank and others. The European development bank, international financial institutions. I would envision a way that we could bring off the sidelines the $12 to $13 trillion that is currently in net negative interest status in the world.

That is the real way to counter violent extremism. That is the real way to work our way out of this challenge that we face, which every generation faces, and build the future.

Now, a final thing I want to mention ]. President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris agreement is an unprecedented forfeiture of American leadership and it is not only not based on any science, it is based on a lie to the American people, that somehow Paris imposed a burden on Americans that is intolerable when in fact it imposes no burden on anybody.

Since Paris, we’ve seen $358 billion invested in alternative renewable sustainable energy, for the first time more on the sustainable ledger than on fossil fuels. Solar nowbeats coal.

But even before President Trump walked away from Paris, 29 states in the United States embraced a renewable portfolio standard. And another eight states have a voluntary standard so 37 states in total of our 50-state nation are going to now be committed to meeting Paris and beyond. And those 37 states represent 80% of the population of the United States of America.

As secretary, I had the privilege of going to Svalbard with my good friend, the Norwegian foreign minister. And I saw what is happening to the Arctic first hand. And then I went to Greenland where every day 86 million metric tons of ice is breaking off, calving, from the glacier on the Greenland rock and falling into the fjord and going out to sea and melting. That 86 million metric tons represents enough water every day falling off to take care of all of the greater New York region for one entire year. That’s what we’re losing.

But what struck me was every one of the scientists there said to me ‘Secretary, you are really not going to understand this until you go to the Antarctic.’ What I saw there was just so disturbing. Three miles of ice in some places, thick, but the pressure of the ice pushes the continent down slightly and the water is coming in underneath and it’s warmer water now than it has been and it’s destabilizing that ice.

It’s happening, right before our eyes. Species are moving, fires are more intense. We have changes in where certain fish stocks are, where certain things grow. Every year is the warmest year in human history. Last year, last July, the warmest July in human history. Last year, warmest year in human history except for this year. Last decade warmest decade in human history. The decade before that, second warmest in human history. Decade before that, third warmest in human history. I mean even kids in middle school can understand that something’s going on and that public responsibility requires that you respond and do something about it.

I am an optimist notwithstanding everything I just said. I don’t see the glass half empty, I see it half full. And I’ll tell you why.

When I was a kid in college and some of you may have been there the same time with me, freshman year we almost had a war with Russia over Cuba. Sophomore year, President Kennedy was assassinated and we thought the world was coming apart. And junior year we sent a lot of people down to break the back of Jim Crow in America on the freedoms buses and we engaged in the Mississippi voter registration drive. And senior year Vietnam was pouring over all of us and the draft affected everybody’s choices. And the anti-war years, next year was the year of a sort of revolution in our country in the streets in 1968.

But we withstood all that. We came out stronger. We’ve been through tough things in this country before and I believe that the founding fathers greatest strength is the institutions they gave us which have the ability to work depending on who is leading and what choices people are making.

Comments

Comment policy »