Following two years of intense planning and preparation, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission landed a $250,000 federal grant this week for an innovative project to reduce groundwater pollution in Lagoon Pond.

The grant marks the largest allocation of federal money in the commission’s history and covers the entire cost of an 18-month long project to install, maintain, and test a permeable reactive barrier along the shores of one of the Island’s most critically polluted saltwater ponds. The $250,000 is only a small part of $2.3 million in grants for Massachusetts projects announced Monday by a branch of the Environmental Protection Agency dedicated to restoring coastal ecosystems along the East Coast.

The grant was formally announced at a ceremony on Buzzards Bay attended by Cong. Bill Keating, commission planners and officials from Oak Bluffs and Tisbury.

Because Tisbury and Oak Bluffs share stewardship of the pond, the commission worked with selectmen from both towns to finalize the Restore America’s Estuaries grant application.

“This is a big deal,” said MVC executive director Adam Turner. “Although it’s the commission, we wouldn’t have been able to do it without the help of [Oak Bluffs selectman] Gail Barmakian and [Tisbury selectman] Melinda Loberg. It’s the first big grant we’ve ever received from the feds. I believe that if we do good on this, we’ll be able to get more money and we can clean up these ponds.”

The commission rushed to submit an application for a similar grant two years ago, but was not included among the 2016 Southern New England Watershed projects that received awards.

“During the next year and a half, we became much more active in the EPA process,” Mr. Turner said. “We really did a lot of work. We invited them over here, had a good tour, went to several EPA meetings, and when it came time to submit one earlier this year we were more experienced and more well known.”

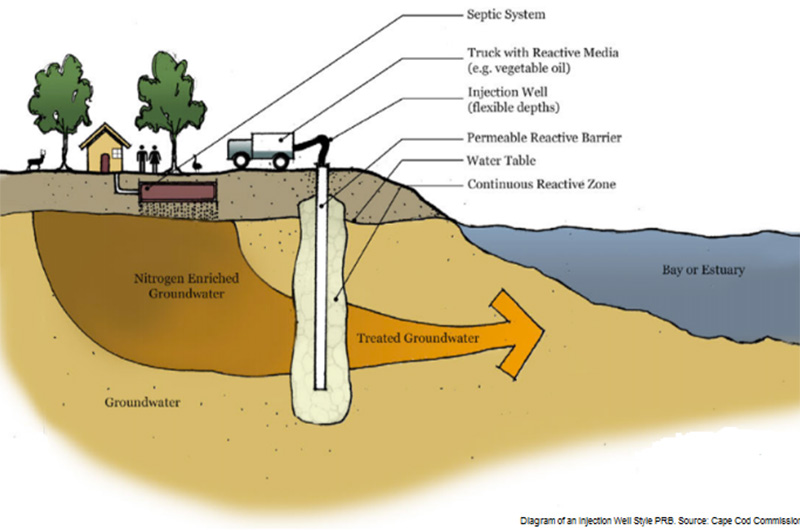

Nearly all the major estuaries on the Vineyard are impaired by nitrogen, a nutrient found in wastewater and fertilizers. Most of the nitrogen in Island ponds comes from septic tanks that discharge into groundwater after treatment. Too much nitrogen can lead to algae blooms that create anoxic conditions, choking out other species like eelgrass and shellfish. Just as widespread development on Cape Cod has devastated most of the 45 freshwater estuaries, recent construction along the shores of Lagoon Pond have also put its future in peril.

In 2015, the Massachusetts Estuaries Project concluded that 13,016 pounds, or 35 per cent of the current nitrogen load entering the pond must be removed in order for it to comply with the federal Clean Water Act and remain a sustainable water resource.

Two years ago, the estuary study prompted the Tisbury board of health to pass legislation requiring property owners to install denitrifying septic systems in all new construction. The grant comes as the next major step in the Island’s effort to restore Lagoon Pond’s recreational, commercial and aesthetic value,

“The technology works, the technology always works,” Mr. Turner said. “It’s not new. It’s how do you get the mediums to do it.”

According to Mr. Turner, $250,000 provides the commission with enough money to contract the construction of a 200-foot wood chip barrier that stops nitrogen plumes and converts them to gas before they reach the pond’s shore.

As Mr. Turner said, the question isn’t whether the barriers work; it’s where to put them. The grant will allow the commission to conduct micro-site studies to determine the slope of the nitrogen plumes and the most effective barrier location. In order to maximize the interception of nitrogen molecules, the barriers have to be installed perpendicular to the groundwater flow, a process that takes ample time and diligent research.

“Before we put anything in, we’re going to do a lot of testing,” Mr. Turner said. “The problem with these things is that they don’t catch all the nitrogen, but we’re going to do testing to make sure that this one does.”

The commission plans to work with its research partner, the University of Massachusetts, to perform the micro-site studies and monitor the barrier once it is in place. Mr. Turner said the commission has not yet put out a request for proposals to build the barrier, but said the MVC plans to contract out the construction. The wood chips that compose the barrier generally maintain their effectiveness for 30 years.

“We still have a lot more work to do,” Mr. Turner said. “We have two sites that we’re looking at, so we’ll figure out which one we’re going to use.”

The 200-foot barrier won’t serve as a panacea for the decades of groundwater contamination in Lagoon Pond. Rather, Mr. Turner sees it as a potential test site. Along with Lagoon Pond, Lake Tashmoo faces a similarly dire threat from nitrogen pollution, while other Island ponds have risk levels that range from “clean” to “moderate.” If all goes well on this first project, Mr. Turner foresees more money coming the Island’s way for even larger coastal estuary restoration projects.

“It shows that we are a laboratory for these innovations,” he said. “The bottom line is to clean up the ponds. It’s great to get grants, it’s great to get innovations, but the real benefit is to have cleaner water.”

He added: “We have a good opportunity. It’s up to us now to perform.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »