When Leah Palmer started her job as director of English language learning programs for the office of the Vineyard schools superintendent in 2012, 73 Island students needed support for learning English.

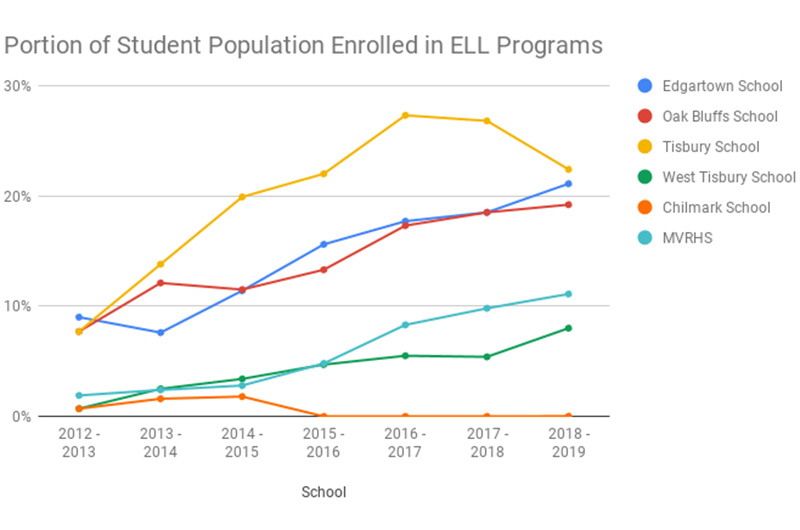

Today that number has more than quadrupled. There are now 327 students in English language learning (ELL) programs in the Island public schools, making up more than 15 per cent of the student body, five per cent higher than the state average. On Martha’s Vineyard, most ELL students speak Brazilian Portuguese as their first language.

“It’s huge growth in numbers and programs,” Ms. Palmer said. “We have 12 teachers now. When I started, we had five.”

The school census for the current school year was conducted Oct. 1, and numbers show growth in ELL programs almost across the board. Ms. Palmer said the academic pace in Massachusetts is accelerated, and it can be difficult to keep up.

“We move fast in school and it’s very rigorous and to be able to give time to develop English language skills — it means they’re missing out on instruction.”

Ms. Palmer said that most Island ELL students grew up speaking Brazilian Portuguese at home in the U.S. She said students who begin ELL classes in kindergarten typically graduate from the program proficient in English by the fourth grade. Students in the program after fourth grade are often newcomers.

She said it has taken a lot to keep up with growth in the last few years.

“When a program grows this fast, staffing it is a challenge. Matching the student needs with our staff has been hard,” Ms. Palmer said.

Edgartown added a third English learning teacher this year to support the school’s 78 English learning students. Oak Bluffs is looking to hire a third teacher for its 82 students in the program. The Tisbury school added a third teacher last September. At the high school, principal Sara Dingledy said she is looking to hire a third English language teacher to support the 73 students learning English there and to provide additional interpretive services.

Since 2016, general education teachers with one or more students who need English support in their classrooms are required to train for a so-called Sheltered English Immersion Endorsement on their license. Training for that endorsement helps teachers make lessons more accessible to students who don’t speak English by modifying their language, explaining the way they are using language, and identifying key words, Ms. Palmer said.

At the Edgartown School, the percentage of students in ELL programs has continued to climb since 2013, topping out this year at 21 per cent.

“With any growing group within the general population, you have to adjust,” said Edgartown principal John Stevens. He said in addition to ELL teachers, the school has a full-time interpreter tasked with communicating with Brazilian-Portuguese speaking parents and translating school documents.

“When there is an event at school and we are inviting families, we want to make sure interpreter is there,” Mr. Stevens said. “It permeates all aspects of the school.”

As with other public schools, students who speak a language other than English at home are screened when they enroll in the Edgartown School and rated on the state-approved English

proficiency scale of one to five. Level ones and twos are the least proficient, and are required to have two 45-minute sessions of English language support per day. Mr. Stevens said scheduling those sessions for students in different grades, proficiency levels, and course schedules is a challenge.

“Do you pull them out [of class]? Do you push the [ELL] teachers into the classroom? The coordination of that creates an incredible amount of detail to look at and satisfy in terms of scheduling,” he said.

Oak Bluffs School principal Megan Farrell echoed the challenge of scheduling. The Oak Bluffs School has seen increases in its ELL population every year since 2012. Currently, more than 19 per cent of the student body is in the program, up from just 7.7 per cent six years ago.

“We’ve added additional teachers to our staff, and we are also engaged in imaging learning software which is an individualized learning tool to help with English acquisition,” Ms. Farrell said.

The Oak Bluffs School employs an interpreter to communicate with Portuguese-speaking families and Ms. Farrell plans to hire a third ELL teacher for the 2020 school year. This year, 82 students are enrolled in the program.

At the Tisbury School, three ELL teachers support 65 students. In 2016, enrollment peaked and more than 27 per cent of students were in the program. This year, 22 per cent of the student body participates, up from 7.7 per cent in 2012.

The Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School has 12 children enrolled in its ELL program.

The trend is not confined to down-Island elementary schools.

“It definitely started with down-Island schools, but it has moved to all the Island schools,” Vineyard schools superintendent Dr. Matthew D’Andrea said.

The West Tisbury School houses English language learning programs for the up-Island regional school district. Two ELL teachers support 28 students there, and eight per cent of the school population participates in the program.

At the regional high school, 11 per cent of the population recieves ELL support. In 2012, the number was less than two per cent.

“We are going to be talking with school committee soon about the need to expand staffing to support our ESL population,” principal Sara Dingledy said in an email.

Liz Bradley has taught English development for grades six through eight at the Tisbury School for five years. She said she and other teachers use multiple approaches to support students learning English.

“We can support them with modifications in testing and in the amount of reading materials they need to cover,” she said. “We can group them differently or change the pacing of their work.”

She said classes go beyond studying English itself.

“When you’re teaching language . . . it’s boring to just talk about grammar,” Ms. Bradley said. “We talk about literature and science and the weather.” She co-teaches an alternative math class with a math teacher and a bilingual assistant teacher. She said students in that class are picking up elements of math and English at once.

Mr. D’Andrea said he is pleased with how the school system has adapted. “We want to respond appropriately to the needs of the Island and these students as they come here,” he said. “I want our schools to be able to provide them with the education necessary to learn a language, but also to be academically proficient.”

Comments (18)

Comments

Comment policy »