On a chilly Wednesday night, Johnny Hoy and the Bluefish are packing them in at Offshore Ale Company with steamy blues and hot rock ‘n’ roll. The band is at the pub for their regular Wednesday night gig because their normal venue, the Ritz Cafe, is closed for its annual brief winter break.

There is no place to dance, so patrons are improvising, twirling near the front door and near the end of the bar. The bartender taps out a beat on the dishwasher rack, and the waiters are two-stepping between the crowded tables.

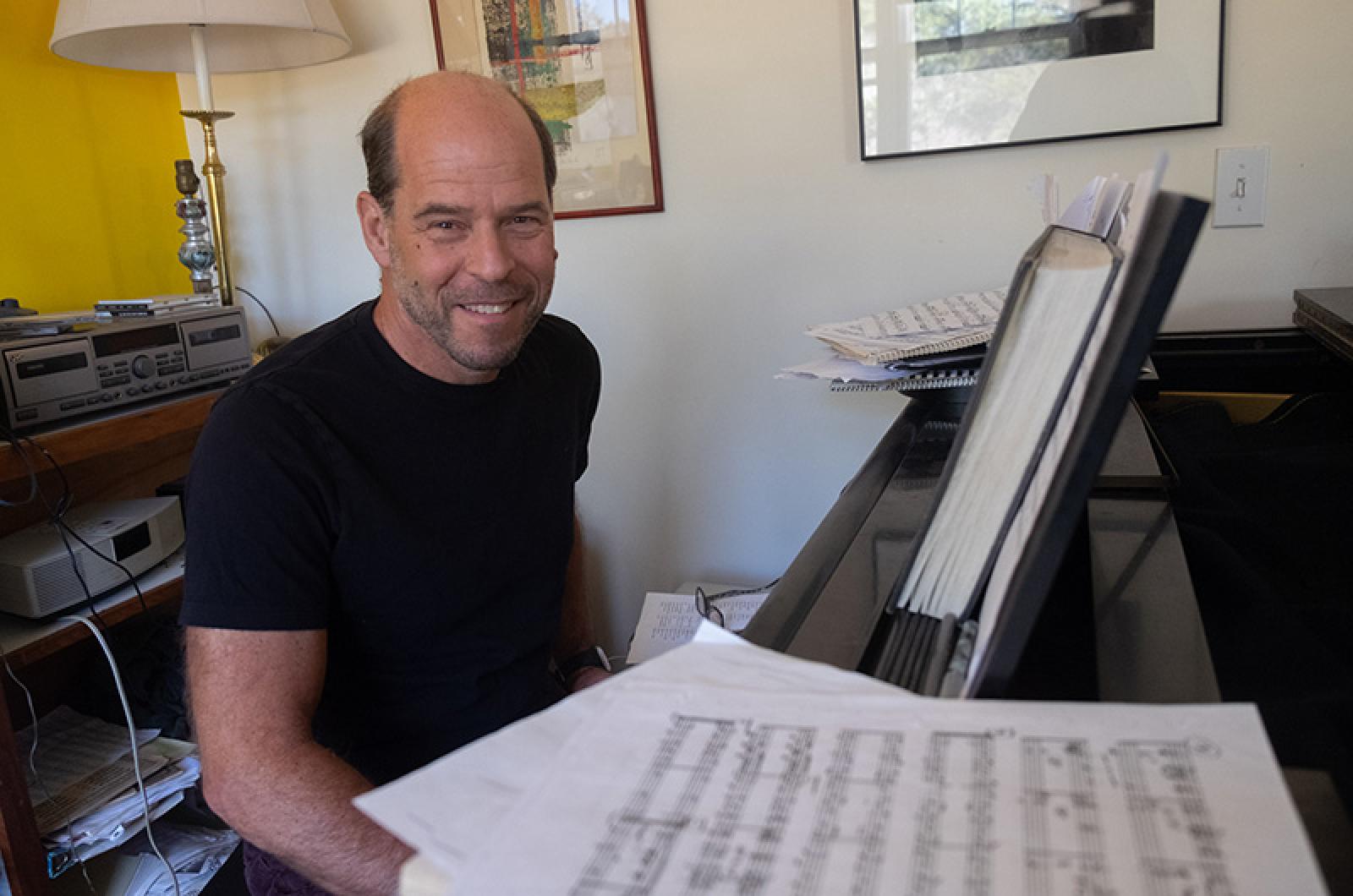

Jeremy Berlin sits crammed in behind the hostess station, under a large pole-mounted speaker, driving the infectious music on his electronic keyboard. His hands dance over the keys, carrying the melodies of a quirky repertoire of blues, rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly, popular covers and more.

Mr. Berlin’s life has always been tangled up in Martha’s Vineyard. Growing up in Cambridge, his family spent summer after summer on the Island. While attending Wesleyan University, it was a natural fit to continue his summers here. He got a job that suited his musical life.

“I came back in college to work on a beach,” Mr. Berlin said this week in a conversation with the Gazette. “Thought it was just a summer job, which it was, but it lasted many years. I could sit on the beach during the day, read lots of books, go out and play music at night, and it turned out to be a pretty good life.”

A pretty good life, indeed. Now 56, Mr. Berlin remains an anchor in the Island’s musical scene with one long running gig as jazz player and another as a blues and rock ‘n’ roll musician. Beyond his regular gigs, he plays dozens of other performances throughout the year from private parties to art shows to a very busy wedding season.

Early in his life he was exposed to music, but his parents didn’t foresee the direction of his musical career.

“There was always music around, though it was all classical,” Mr. Berlin said. “My parents had no inclination toward jazz or popular music. They had no knowledge of it or no taste for it. There was no Ray Charles playing in the house when I was growing up. There was no Charlie Parker playing in the house.”

He began playing piano at the age of six, and took lessons all the way through high school. He found himself however, often departing from the notes on the sheet music.

“I improvised from the time I was a kid, always played by ear,” he said. “I got obsessed with jazz when I was 16, discovering it on the radio, then hooking up with a bunch of friends. A bunch of 18-year-old boys were thoroughly immersed in be-bop and jazz. We jammed all the time.”

It was an unusual turn for a young musician. The jazz club scene was shutting down, the best players in the world were having trouble finding steady work. Some prominent observers declared the genre on its last throes of life.

“We didn’t think it was dead. To us it was entirely alive. It was new and incredibly compelling, and frightening because it was so hard. I didn’t really understand what I was doing. I was just kind of following my ear.”

After college, he stayed on the Island. A happenstance connection led to an offer to play a wedding. He put together a band, and the gig was successful. Without really intending it, he found himself in much demand for the growing wedding industry on Martha’s Vineyard. It was at a wedding gig that he met Johnny Hoy, an introduction that was to shape much of his professional musical life for the next two decades. But it wasn’t until a summer several years later that he was asked to sit in with The Bluefish in a semi-regular capacity.

“I remember going to him at the end of the summer and saying, so am I in the band or aren’t I,” he said. “What’s my status here, I’m kind of confused. He said ‘You want to be in the band?’ I

said yeah. He said ‘Well we’re going to Maine tomorrow.’ So we got in the van and we drove to Maine. That was nearly 26 years ago now.”

He had very little experience playing blues and rock ‘n’ roll, but quickly found the root of the music.

“All this music comes from the same root and the same place, but they kind of grow and they become like different languages, different lexicons, different slang. You have to understand what the rules of the languages are. If you’re playing blues you can’t throw down a fancy jazz chord. If you’re playing jazz you can’t suddenly start playing blues licks on top of it. That being said, you absolutely can do that when you know. You basically learn the rules and then you forget them. You know when you can break them. It’s a fascinating kind of duality. You just have to have the right instincts.”

For the past 16 years, Mr. Berlin has shared a jazz gig with guitar player and bassist Eric Johnson on Tuesday nights during the off season at Offshore Ale.

“Every year that passes I realize how lucky Eric and I are to have something that has lasted that long. We can play the music that we love to play and that is what is expected of us and that’s what people want to hear. We have been able to work up our musical relationship and our repertoire in a way that is quite rare. Jazz gigs are so hard to come by, anywhere.”

Mr. Berlin said he has been thinking lately about the question of nature vs. nurture. The prompt for his contemplation is his two children, who are both firmly rooted in musical lives, with obvious talent. He rattles off a half-dozen Island musicians of his generation, who have progeny also making their way in the musical world. Mr. Berlin’s son Silas, 21, is a student at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, spending hours of his free time playing classical piano, and planning for an upcoming performance on the Island.

“Silas starting playing piano at age six. From the very, very beginning you could tell there was a lot of music in him. You go to a recital and there’s 15 kids playing the same tiny little piece, and you know which kid is robotically getting through the thing, and which kid somehow innately, intuitively feels the shape of the music. Silas was one of those.”

Mr. Berlin said he is both proud and happy that his children have picked up the music bug. He speaks in awe of his five-year-old daughter Elda, who recently brought down the house at a local talent show with a vocal rendition of the song My Funny Valentine.

“Elda, I think, in many respects outshines all of us,” he said. “She is one of the most natural musicians I’ve ever come across. Her pitch, her understanding of whatever genre is playing. Her musicianship is sort of astounding for somebody of her years.”

With thousands of performances behind him, and many more ahead, Mr. Berlin has come to appreciate, more than anything else, the connection that happens between people when music is added to the emotional equation.

“I know enough music, and enough about human beings, to make the connection between the people and the music that I’m playing. I think that’s what keeps me working.”

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »